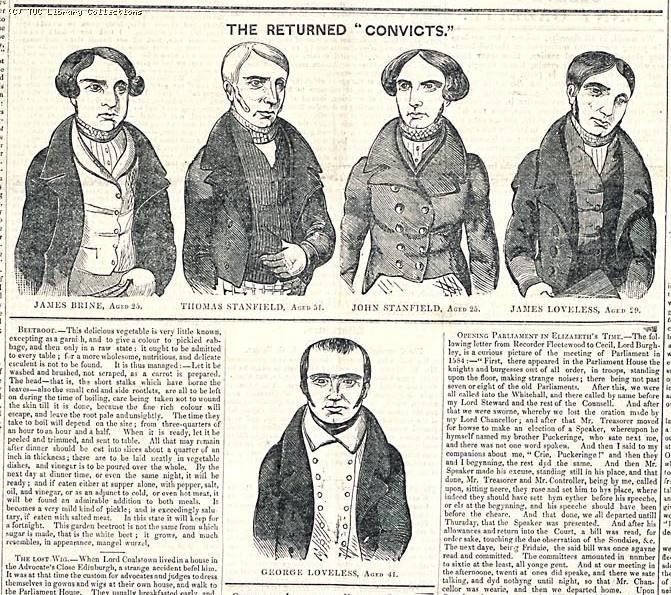

After the men from Tolpuddle had been been found guilty, workers all over the country began to fearlessly proclaim that it was a blatant miscarriage of justice, that there was a law for the poor and another one for the rich. If the law banning appurtenance to a trade union had been repealed, they asked, how was it possible for the judges, whom every Englishman knew to be the fairest in the whole world, to instruct the jury to find these men guilty? And if they were guilty, why could they not have had a short jail sentence? Newspapers published features supporting the men, now dubbed Martyrs, condemning the unfair sentence, but they had been dispatched to Plymouth in great haste in order to forestall a possible change of heart. It was not uncommon for a transportee to be left to rot in some hulk for six months or more before being taken to the convict ship, but the Tolpuddle six were on the high seas in a matter of weeks. The wicked men who had the power thought that once the men were out of the country, the protests would die down, but die down, the protests did not.

Many people maintained that the status quo was the enemy of progress and had to be resisted; the most vociferous among them, and ultimately the most effective, was George Wakley, a doctor of medicine, member of parliament and a reformer, who knew what many people chose to ignore, that there was a lot of injustice in the land, and that the system always benefited the Haves. He had created The Practitioner, a journal in which he had attacked the profession for its known malpractices, its preoccupation with making money as opposed to curing the sick. When he was elected as member for the Finsbury constituency, he chose to make his maiden speech on what he called a miscarriage of justice, to the indignation of his fellow parliamentarians. This drew even more attention to the case of the Tolpuddle Six. He reprimanded the house for pretending that they did not know that the law which made trade unions illegal had been repealed, and for their wilfull misrepresentation of the Mutiny Act and dishonest invoking of so-called swearing of secret oaths. People believed, with reason, that it had been decided in advance to find the men guilty, he declared — like in Ancient China — where it was customary to execute the accused first, and try them later. Why else, he demanded, would the Prosecution revive a law which had been dormant since 1797? He reminded the house that the Jury consisted of farmers and mill owners, men who had close relationships with the landed gentry and who had much to lose by a process which would lead to the worker earning a fairer wage. The foremen of the Jury, he reminded the House, was the Hon. W.F.S. Ponsonby, one of the richest landowners in Dorset. That in our land, a man is tried by his peers, he said in a voice shaking with emotion, is a big lie. The men were not tried by their peers, it was a case of the poor being tried by the rich!

Although this was his maiden speech, he knew how to handle drama; he played his trump card last.

‘The House was no doubt aware of The Orange Order,’ he said, adding slyly, ‘seeing that most of the honourable members sitting here today belong to it. Can I remind you, gentlemen, that you too swore a secret oath when you were received in that respectable Order? Yes, gentlemen, you did; I challenge you to contradict me. Why is it that you gentlemen, can take a secret oath and not be sent to Botany Bay, whilst some honest workers, in whose numbers we find preachers of the Methodist Church, doing the same thing get condemned to a sentence which many believe is equivalent to the Ultimate Penalty? Dare I suggest to you, honourable members, that in our country, reputed the world over for its just laws, that Dissenters are seen to be excluded from the benefits of its tolerance of democratic values and freedom of speech and worship? One law for the rich and one law for the poor; one law for the followers of the established church and one law for the followers of other Christian denominations?’

The embers of dissent were fanned by the increasingly vociferous controversy, and it did not take long for the king to grant a free pardon to the men who had suffered so much pain and humiliation. George Loveless, who had earned the respect of everybody in Van Diemen’s Land, including the Governor’s, was informed of the success of the campaign for his release by the latter himself. James was in prison in Port Jackson waiting to be taken to Norfolk Island, when the news arrived at Taj Mahal. The moment Coldwell was appraised of the king’s pardon, he took prompt measures to stop his imminent embarkation; if the King had pardoned a man, it means he was as innocent as a new-born babe, and no one believed in the power of the law as fervently as he did.

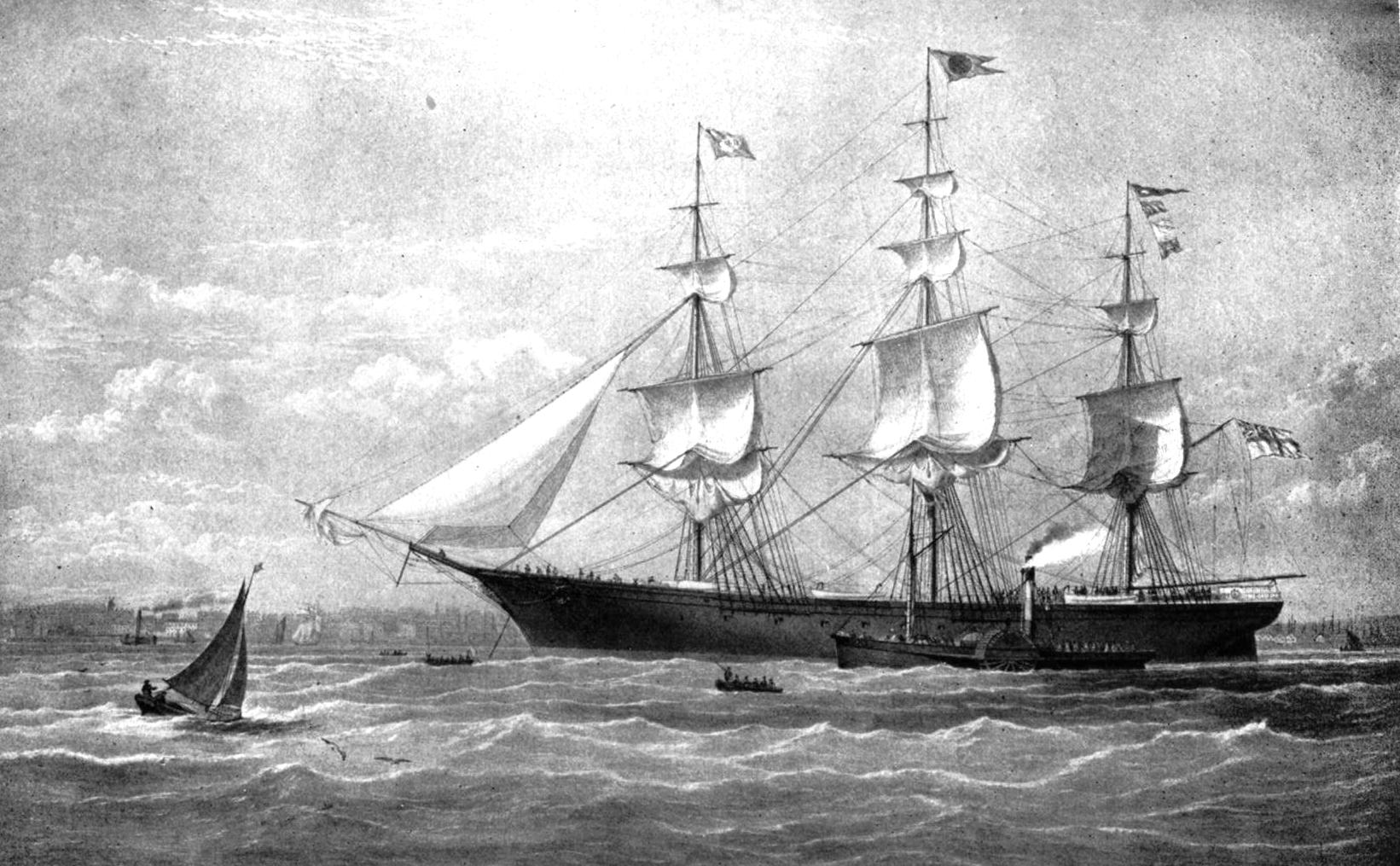

James was seriously ill in prison, and the governor had feared that he might die before reaching that notorious island. He was delirious when the news came, and had no idea what they were telling him. The doctors took great care of him, and declared that he was just about fit enough to travel. He was taken back to Port Jackson where he hardly recognised George and the others. In his delirium, he kept calling the name of Annie, but he had no idea that he was being taken away from her. They were all promptly conveyed on a ship returning them home. When, with the tender care of his fellow Martyrs he finally regained both his health and his clarity of mind, and realised that he was being taken back to England, he was shattered, although until he had met Annie, his dearest wish had been a review of the trial leading to his return home. There was clearly nothing he could do, but he was determined that once he reached England, he would do everything in his power to go back of his own volition to her, at whatever cost.

Annie had been distraught at being separated from James, and soon after began to feel weak and feverish. Amelia was greatly alarmed, and called the doctor, who found that she was with child. She kept calling the name of James, and was shocked to hear that he was going to spend the rest of his life on that hell on earth that was Norfolk Island. She promised herself that she would go join him there; she would go on her knees and beg Mr George to help her in this; in spite of James’ experience, she thought of him as a fair and upright man, and was sure that he would help.

In the meantime, Bruce heard of Annie’s condition. This cheered him up no end, for he was sure that no one else would now want a woman with a child by another man. His blind passion for the woman was such he would have no hesitation in taking her, and she of course would have no choice. He would love and cherish her child. He was reconciled to the idea that at first she would not reciprocate the great passion that he nurtured for her, but how could she not end up seeing the depth of his feeling for her?

Shortly after, a much debilitated Annie gave birth to a baby girl prematurely, and she as well as the baby were in a precarious condition. The doctors worked day and night to save them, but in the end Annie was too weak and died in the arms of Amelia. The baby survived and seemed well. When he heard the news, Bruce went mad with grief and remorse. Her death was entirely of his making, he told Johnson Johnson, the only man he considered his friend. Surprisingly he blamed the black man; why had he been so gullible? Why had revealed the secret to him? If he had been less stupid, she would still be alive, happy with another man, but all he ever asked for was her happiness. Johnson Johnson was much touched by the man’s genuine grief. But he had heard that his real friend James was bound for England, and he rejoiced for him.

Annie had always marvelled at Amelia’s kindness, and on her death bed, she was much comforted by her solicitude. It brought a smile to her face as she wryly told herself that sometimes a mistress and a servant can change places. She died in the certainty that the mistress would do her best for the baby. The lady grieved for the servant like for her own sister, and George was deeply touched by this. He always admired his wife for her compassion, which was why he had fallen in love with her in the first place. She had readily agreed to forego the fine saloon life of London to follow him to the outback. He had been heartened that the woman he had suspected of marrying him for his money, did truly love him. Now she found solace in the new baby. In no time at all, she was considering the baby like her own, fussing over her, hiring a native nursemaid whose own baby had died so she could breastfeed the little motherless mite. Nobody was surprised when she decided to call the child Annie. No mother could be as besotted by the little creature as she was, and George was delighted for her. It was George who one day asked her if she would like them to adopt Annie. Annie Coldwell grew up in the Coldwell household, surrounded by doting parents and not knowing that she was adopted, until her fifteenth birthday.