(Extracts from the very intimate journal of Fanny Bell-Mowbray)

Please please destroy in the event of my death.

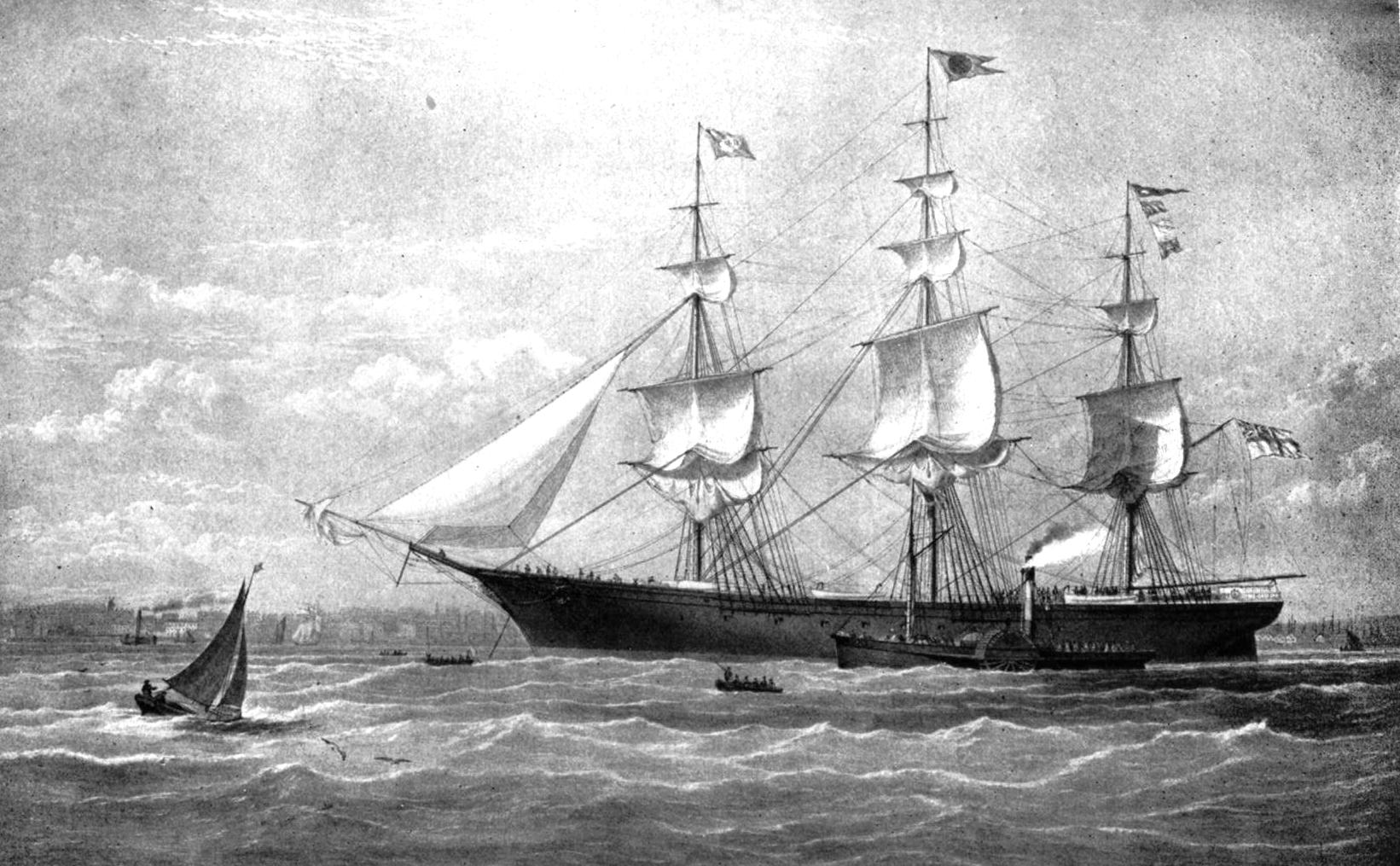

Nineteenth of May 1846. I have never kept a journal in my life, but now that I am going to be on this sailing clipper — The Indigo Sky — for upwards of ten weeks, at the mercy of the trade winds I have resolved to record the events of my so-far dull, bordering on uninteresting life. I am writing this because sometimes, when one is at the crossroads, one has to take stock, and writing this is perhaps the best way of achieving this. The ship sailed out of Liverpool yesterday bound for Port Jackson, New South Wales. I would have preferred going on one of those new-fangled steamships, but at the moment they go mostly across the Atlantic. But I am not complaining; this is a gallant little English ship. The cabin is obviously cramped, but my companions are two sweet and good-natured elderly widows. I have not enquired of them to what purpose their visit to the Antipodes was, and I daresay they have not volunteered the information. Although they are dressed in fine clothes, they have a common speech. I am not a snob, I swear, but I found this striking, and took the decision to note everything interesting. I am going on a visit to my dear brother George Coldwell in Hunter’s Valley, where he is a big landowner and one of the most influential men in New South Wales.

I have to laugh! Here am I talking of elderly widows, as if I were not one myself — albeit not elderly. I am not yet thirty, but forsooth a widow nonetheless. I was married at nineteen to Captain Quentin Bell-Mowbray, eight years my senior, shortly before he was due to sail for India, to join his regiment there (The 22nd Queen’s Regiment). We spent no more than a week together. The Captain and I met when his father organised a ball in his honour in his Stroud home, with the view (which we now know) of helping his son find a desirable bride before he went back to join Sir Charles Napier in Poona. Mrs Elizabeth Bell-Mowbray had made sure she invited all the eligible maidens around, and I was flattered that Quentin picked me, God only knows why! I was a plain and ordinary girl with few accomplishments. I daresay my plain features have not improved with time. One does not have to look too closely to see a grey hair or three amid my otherwise jet black hair, for every time one appears and I pull it out, like the Hydra of Lerna two new ones take its place. Over the last years, I have oft asked myself if I was ever in love with Quentin, and I can verily say that I know not the answer to that. Although Quentin is the only man I have known in the biblical sense, I have no abiding recollection of the four occasions when we indulged. Maybe I am just grateful that he chose me over the likes of Pamela Wellerby-Courtney and Cicely De Vere, both manifestly much better endowed than me in every sphere. I do not recall feeling like a Hindu widow throwing herself onto the funeral pyre as her dead husband is being immolated when I heard the sad news of his passing. Sir Robert, my father-in-law explained to me (with the help of a map) how it happened.

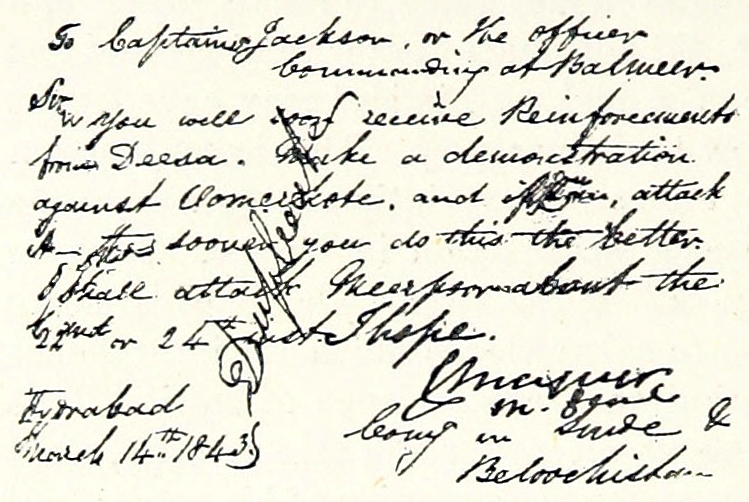

The three amirs of the provinces of Sind, with whom we had signed treaties, started plotting with other tribes, with the intention of reneging on the undertaking they had given us (explained Sir Robert), and Sir Charles Napier, ever the man of action, decided that there was only one thing to do, to confiscate their lands: neutralise them and annex the territory.

Quentin had written to his father (a letter which we received after his demise) about how Napier had sent him and a force of only three hundred and fifty men on camels to capture the fortress at Imamghar, which they took, unopposed, after which they blew it up in order to prevent the enemy from using it if they retreated. A week later, buoyed up by his initial success, Napier decided to consolidate before descending upon Hyderabad. That was the last time we heard from Dear Quentin.

However, Sir Robert’s friend from the War Office sent him a detailed letter later. The amirs, it seemed, had formed a coalition and gathered together a force of five and twenty thousand men, and they were entrenched in the bed of the Falaili river. Napier, disposing of two thousand and eight hundred men, despatched two hundred of them to help Captain Outram start a forest fire to stop the enemy using a crucial flank.

The enemy had more guns and men and were strongly posted on a curve of the river, with massive reserves in the skikargah, or woody enclosure. Sir Charles thought that the situation was desperate, but noticing a small opening in the wall in his right flank, he ordered Captain Tew to take a company into the breach, and defend the position even with his life. The good captain did as he was told, and when he died, my Quentin took command of that brave band of soldiers, and fought against overwhelming odds. He died too, but the gap was successfully held to the very last. The natives fought with valour, but we routed them all the same. The two men were both awarded a posthumous V.C. later.

And lo and behold, I, who hardly shed any tears at his death, am now crying hot tears as I write these lines. My poor brave heroic husband!

Sir Robert used to love telling visitors what a big part his dear son had played in Napier’s capture of Sind for us. For once in my life, I was able to see the benefit of all those years I struggled with my latin, for when Sir Robert gruffly told the PECCAVI joke, I immediately understood it. After he had captured Sind, it seems that Sir Charles had sent a one word message to the Foreign Office: PECCAVI. I have sinned (a rather clever little pun, I thought).

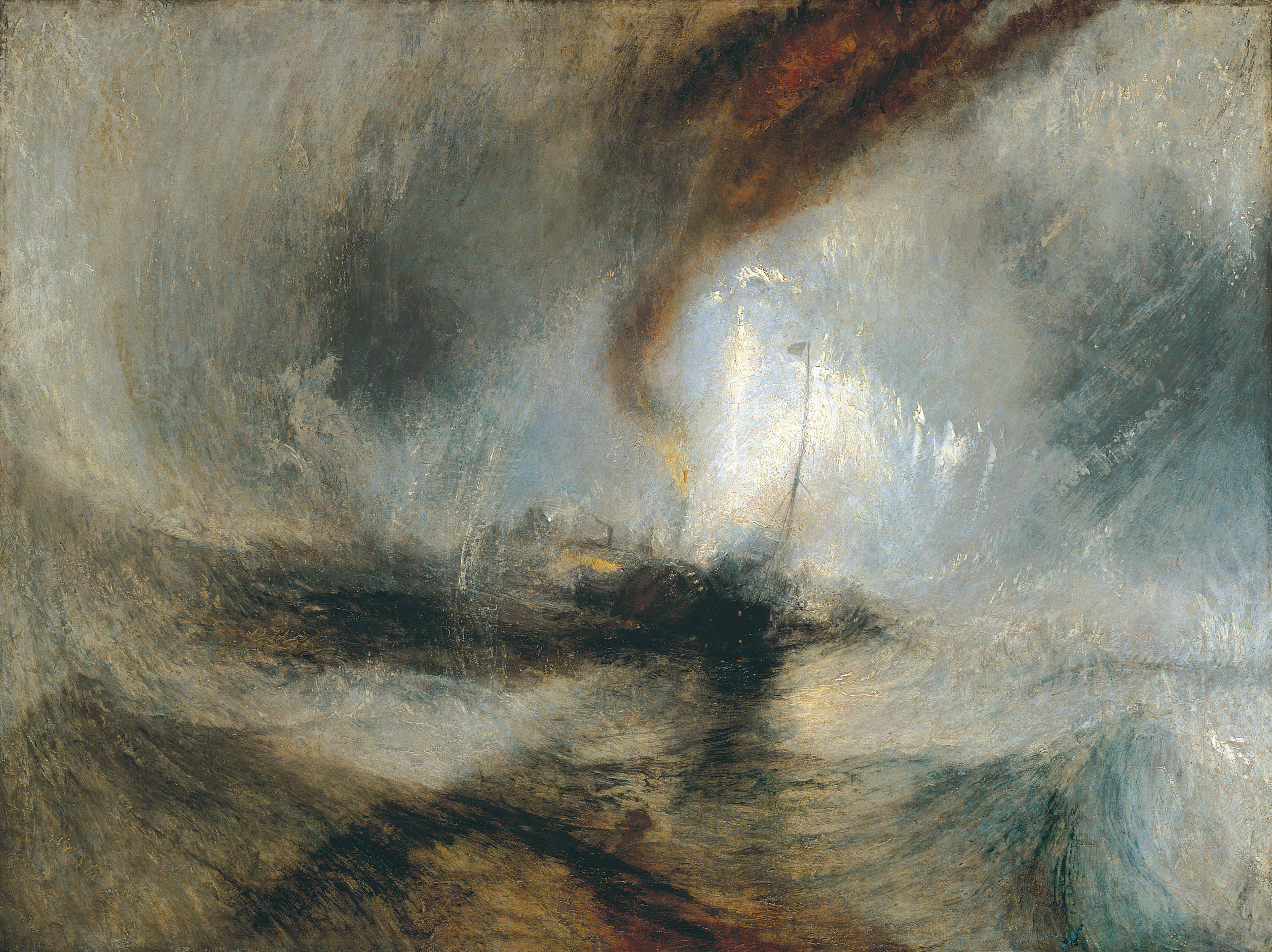

Twenty-second of May 1846. It was a rough night, the sea was very choppy and my stomach churned as the ship pitched and tossed. Surprisingly the elderly dears remained serene and unperturbed.

It seems like a lifetime when the tragic events I wrote about took place, and I have been a widow since. When Sir Robert died, with George away in New South Wales, I was left with Marchmont Manor and the estate, which consisted mainly of housing and tenant farms which bring me a pretty penny without doing any work for it, which I sometimes think is grossly immoral. The governance of the everyday matters of the estate is in the hands of the steadfast John Merryweather, as upstanding and honourable a man as breathed our English air, and for whom I have the greatest esteem. George who acquaints me in every letter of how happy marriage has made him keeps intimating that I should find myself a new husband before I get past the age, and although I am not opposed to the notion, I have not as yet met anybody to whom I have been inclined to give an encouraging nod.

Dear George humorously intimates that the deck of a clipper might well be the best place for a romance to burgeon and then blossom in the fertile atmosphere of Captain’s balls and what not. So far I have not seen or spoken to any interesting prospective suitor. I despair at the thought that there might be none on board.

Third of June 1846. We have been becalmed. Some passengers say that this is tiresome in the extreme, but I find that lazing on a deck chair in the sun — and there is plenty of it — whilst the clipper is rocking ever so gently, watching a baleful sea, flying fishes and a few fearless albatrosses and what not displaying their acrobatic prowesses is calm-making and soporific. No, I mean relaxing. I can feel all the muscles in my body loosen, and I enjoy a sensation of well-being which I cannot properly describe, except by saying that it gives me the impression of listening to my blood coursing down my veins — if that’s not too pompous a way of putting things. The Captain informed us that we are in the region of the Bay of Biscay, but although Spain is nearby, we can see no land at all, although the occasional flock of sea birds is testament to the proximity of land.

My elderly widows, two sisters-in-law, have confided to me that they were on their way to join their sons, who were cousins, who had been transported to Botany Bay in the thirties, and who, at the end of their term, had worked their fingers to the bones, and were now partners in a large sheep-rearing establishment. The boys had sent them the money for their expenses, and had insisted that they shall travel first class. They swear that their boys, as they call them, were blameless and had been wrongly condemned, on the perjurious testimony of a debauched nobleman who had found it expedient to lay the blame for his crime at their door. Even if there isn’t always man’s justice in this world, I surmised, there is always God’s, for He, in his wisdom, had thought fit to reward those two innocent men for the iniquities done to them. I wanted to take those two dears into my arms and embrace them, but I did not dare.

I have been reflecting on my own fate lately. When you are in a confined space with nothing to do, you do tend to think about events in your life. George and I were the only children of our parents. We were always very close although he is seven years older than me. Whilst he went to Eton, I was educated at home by a Dr Washwell, a retired parish priest. He was a wonderful old man, and I have to laugh as I recall how he used to employ the same technique in teaching as no doubt he used in the pulpit, speaking in a loud hectoring voice, wagging his fingers, although I never found him threatening, as I knew that he was a gentle old dear. Sometimes in the middle of a latin lesson, he would forget where he was and start talking about Marco Polo or Chevalier Bayard, in heroic terms, as if they were some admirable saints from the bible. He encouraged me to read, but he had clear ideas about what to read and what to avoid. Captain Marryat was in, but Dickens he frowned upon — which was probably what turned me later into an ardent reader of the latter out of curiosity. I read as many of the books that he disapproved of, indubitably because I had (still have?) a perverse nature. I must say in all sincerity that I have never in my life, come across anything in any book, which has given me any wicked thought or impulsion, and I cannot envisage how reading can be anything but beneficial to one’s soul. I often wish that I was born a man, for women are limited by the restrictions imposed by our sex. I would have liked to have been able, like George or Quentin, to fight for my country. And die even, for it’s an honour to lay down one’s life for one’s king.

(Here follows a series of musings unconnected to the development of her history)

Seventh of June 1846. I am finally getting used to life at sea. I can imagine living like this for the rest of my life. We acquired fresh supplies in Aveiro, where we halted for twenty-four hours. There is a nice feel to Portugal; it is a rugged and beautiful place, and the denizens are handsome and pleasant, albeit dark. Not that I am imputing their dark colour to negro blood, Heaven forfend! It’s the work of the sun, and I daresay that their swarthy appearance make them look very handsome albeit in a threatening sort of way.

We are now being served lobsters and prawns regularly, and I relish both of these delicate crustaceans, even if the eating of them is quite laborious.

It is now abundantly clear that if I shall meet an interesting man, it is not going to be on this trip, for there is none. One or two officers have spoken to me, but although they were gallant and polite, I gave them no encouragement as I cannot see the superiority of being married to a man who was away at sea for eleven months of the year to being a spinster. I sometimes think that the condition of spinsterhood isn’t as bad as that odious word ‘spinster’ intimates. Still, I have lived in hope, but now, dear Journal, hope it seems, there is none! Between you and me, I am not all that sold on the idea of finding any husband.

Thirteenth of June 1846. We are now in the Gulf of Guinea. We are sailing close enough to see the land, the coast mainly, but not the details. The heat is unbearable, and all one wants to do is to imbibe water, but it has a taste which I find hard to describe, which discourages one from so doing. I suppose stale is the nearest word I can think of. I have written in some details about our childhood, George and mine. Since there is not much to write about, as nothing unexpected happens on this voyage. We only had one storm which I have described in details earlier, and it was nothing as terrifying as I had hoped. I own to liking those cataclysmic manifestations of nature, storms, thunder and lightning, the sort of downpour that goes on or hours. I suspect these violent natural manifestations find an echo in my soul silently rebelling against my sedentary life.

I might as well confide to you, dear Journal, some of my most intimate thoughts about the family.

George’s wife Amelia is one of the sweetest girls I know. Woman, I mean. We were delighted when George told us he aimed to marry her. I got to know her properly when George went to India on his own, with the East India Company, and she stayed with us for a while because the quarters for wives were not ready. However after a two-year stint there, having impressed his superiors with his dedication to hard work and, I daresay his intelligence, he was given an unexpected promotion, and a big house in Howrah where he was able to take my dear sister with him. Since that time the family and I have seen very little of them. We did not like the idea of their going to Australia, but Papa was convinced that the future was in the colonies, and did everything he could to encourage him to take the plunge. George was unable to resist the siren call of the Antipodes. We were all impatient to hear of an addition to the family, but it soon became obvious that she was unable to bear children. I own to a perverse nature. God knows how much I love George, but I could not suppress the question: How do we know for sure that the fault is Amelia’s and not my dear brother’s?

George wrote regularly, but he did not seem to have the time to go into details, so we just had to content ourselves with news that he was well and had cleared so many more hundreds of acres of land on which he was growing potatoes, wheat or breeding sheep and cattle.

The first time he mentioned little Annie, he did not go into details, and simply said that they were going to legally adopt a little girl whose mother had died. We all thought that the woman who had died might have been another English woman, wife of some other colonist, and we were delighted, both for my brother and his wife, and for the innocent little orphan child. Imagine our shock when we heard from people who had come over for holidays over here, that sadly Annie was a little girl born out of wedlock to a convict pair, he a ruffian who had been involved in plotting a revolution, and she a Gipsy thief. Of course I did not approve, but I supplicated the Lord to give me some understanding. And the good lord never leaves any prayer unanswered. One morning, as I was preparing to get out of bed, a thought struck me: a child does not bear the sins of its parents, and is innocent of their trespasses and I must endeavour to remember that at all times. But to my shame, I no longer considered Annie as my proper niece. My nightly prayers to the Lord to protect my brother and my sister-in-law and my little niece, did not sound sincere, for no one can fool the lord.

As the distance to our destination gets smaller by the day, my excitement at seeing dear George is increasing in the opposite direction. Doctor Washwell had vainly struggled to impart to me the notion of inverse variation, and it’s only today that understanding suddenly dawned upon me. I am dying to see my dear sister too, but the thought of Annie fills me with a kind of foreboding. I have gone on my knees begging the Lord to make me love her truly and without reservation. Please Lord, understand that I truly want to love this innocent child. All I ask of you is that you give me the means of doing that!

(A lot of the subsequent entries are about Fanny’s impatience with herself over her uncertainty of how she was going to react to Annie, and prayers to the Lord to show her the way. There are large gaps which she explains by the absence of anything new.)

Fifteenth of August 1846. It seems that I have lived in New South Wales for ever! It was absolutely heavenly to see my dear brother who, if he looks older, is also much more handsome and dashing than I remembered. I had always wished that he would grow a moustache, and I am delighted that it becomes him so well. I wish he would dress himself a bit less casually, he who used to be so well-groomed. But I understand that in his new life, when he is expected to do all manner of things including manual work, a few of the niceties of life have got to give. I was discomfited and dismayed at first to see dear Amelia with a man’s hat and wearing men’s trousers, glowing under the midday sun as she supervises Aborigines and convicts digging the fields. I have left the best bit last. The good Lord as usual answered my prayers: I immediately took to dear sweet little Annie. She is a sweet loving and caring young thing, pretty as a picture, lissome, dark flashing eyes and although she has lived all her life in the backwoods, deprived of good society, she is naturally gifted, has poise and bearing, and talks very sensibly for a seventeen year old. But there is one thing that I simply cannot abide, she has the voice of a twelve year old, and it sounds odd. It’s probably because she has always been treated like a baby. She likes to cajole everybody, not that I am saying that she has an ingratiating nature. She is just the sweetest child one can imagine. She calls me ‘dearest auntie Fanny’ in the most endearing manner, opens her eyes wide, bats her eyelids, pouts ever so slightly, and anyone would feel like a brute for refusing her anything. But I know she is a good person, and I am already getting used to her. Glory be!

Twentieth of August 1846. This morning, when I woke up, I was full of energy, and thought that I would spend the day working with my hands on the fields, not as a supervisor, but as someone using spades and pickaxes. Nobody thought that I was eccentric or outlandish, so I spent the morning digging a trench which George hopes to use to channel water from Lane Cove river to our fields. I am already using ‘our’. George has intimated that I might consider selling the cumbersome estates in Stroud and join forces with him here, but I am reluctant to contemplate this. I am sometimes aware that I nurture uncharitable thoughts about people, and nightly I ask the Lord to cleanse me of this stain. How could I have allowed the thought that dear selfless George was more interested in what my money could do to further his ambitions for Taj Mahal than for my welfare? I own that back home I am used to being Number One. Here I can never be anything but second to dear George. I would not mind that all that much, but to be honest, dear diary, I am quite keen to get myself a new husband, although I know that I have intimated elsewhere that I am indifferent to the notion; we of the feeble sex must not reveal our true nature to the world. Dear George is still so close to me that he guesses where my doubts reside, and has told me of some wonderful unattached men working wonders on the land in places like Woolongong, Kembla or Gerigong, which I had never heard of. But as he is the most honest man I know, he has not failed to mention that he sees these worthies less than once a year, so where are my chances? This is also something my dear sister has said, no doubt in the name of judiciousness, but I am ashamed of my lack of charity in thinking that deep down she would prefer me out of the way, although dear Amelia has never given me any cause to suppose that. May the Lord make me more charitable in my thoughts!

Nineteenth of September 1846. Understandably, I do not feel the necessity to keep my journal on a daily basis, as life here is very much the same day in and day out — not that I am complaining. It is a good life and I am perfectly happy here. Everybody is so nice. As I said earlier, I very much enjoy helping George in the education of dear Annie, who has great aptitudes, although there are great gaps in her learning. For instance, she thought that outside England, everybody spoke French. The poor dear did not have the benefit of dear old Doctor Washwell. At first I was disconcerted by her readiness to talk about things which, according to me are best left unsaid to any but one’s most intimate friends. She does not hesitate talking about what the beasts in the stable or in the backyard get up to, or about calving or lambing. I blush as I write this, but I caught her one day in the bush, taking down her knickers and easing herself. I prefer to laugh as I am getting used to her lack of awareness. I do not much care when she notices my blushes and laughs at me. I suppose I am getting to be a staid old spinster.

Tenth of December 1846. It seems eerie, but the weather is so hot that I find myself glowing all the time when I am working in the fields. Annie has no compunction in using the word sweating, which, coming to think of it, is not such a bad word, and it describes the process of losing bodily waters very aptly. I may be an old (oldish?) spinster, but I do try to not think like one. I often question myself and am not loath to changing my opinion about things. Father used to say that it was the mark of intelligence to review one’s position in life, although the old dear himself never changed his position on anything, as far as I can recall. I feel so awful when I say less than flattering things about people I have loved, it seems like a betrayal of some sort.

I notice that I am rambling. I meant to say that the hot weather does not seem appropriate with the advent of Christmas. Merryweather has sent many things from home, and we are planning on a memorable celebration. George has managed to get his friend from Great Lakes, Elias Malpas to come spend a week with us. The man owns half of Great Lakes, he says, and he has hopes that the two of us might get on with each other. I cannot hide from you, dear Journal, that my heart is already aflutter with excitement. Shall Elias take to me?

Photo Credit:

Elioth Gruner, Morning Light 1916 (Public domain)

Photo Credit:

Elioth Gruner, Morning Light 1916 (Public domain)

Twenty-third of December 1846. I have never been so angry with George! How could he think that a boor like Elias Malpas… oh, I can’t go on.

Twenty-seventh of December 1846. Yes, he is coarse and drinks too much, I do not much care for his leering at me, but I have arrived at the conclusion that he is an honest hard-working and hard-drinking man. He made us all laugh at the Christmas dinner, he has such a fund of stories about the Aborigines. Those that I have met over here have struck me as decent and hard-working, so I find all those stories Elias told about how stupid they were, how lazy and how dishonest, a bit hard to believe, but he has a way of making them sound very funny if not very convincing. But why do I feel guilty every time I meet Johnson Johnson or Goolagong? I used to like them a lot, but now I am on my guard. George laughed with Elias, but pointed out that as the Aborigines are not used to individuals owning property, they find it hard to believe that things they need and which are available, cannot be taken for their own use. Land, according to them, belongs to the tribe, that is to whoever needs it. I am confused. Elias has been looking at me in a manner which makes me blush. I have hardly spoken to him when we are just the two of us, but as I was helping remove the plates from the table after dinner, he found the opportunity of grabbing me by the arm, when both Amelia and Annie were in the kitchen and George was in the verandah waiting for his friend to join him for cigar and port, and said to me, ‘Can I see you tomorrow when the others are having a rest after lunch? I want to tell you something important.’ My immediate reaction was one of shock and horror that he should presume that I was available for the picking. Then I thought, but I was, so I relented. I do not know what to say if he does propose to me. I am filled with awe but also expectation. Maybe the good Lord wishes me to be instrumental in smoothing out some of his roughness…

Twenty-eighth of December 1846. It was uncanny how easy it was, George said he was not going to have a siesta, as there was some problem he had to attend to, and the gels complained of the heat and said that they were going to rest for a while. So am I, I lied. Elias winked at me. As I am not over-fond of being winked at, I blushed and changed countenance, but luckily no one noticed. He walked to his room, knocking a chair or two over as he did so, and banged his door loudly as he went in. I took a deep breath, and walked towards his door, and knocked. He came to open the door and taking me by the hand walked me towards his bed, and made me sit down on an armchair whilst he himself chose to sit on the bed. His hand touching mine gave me what I can only call a frisson, but I stayed cool. He took off his shoes and socks, and started scratching between his toes. What an uncouth character, I thought, but decided that I shall not pay too much attention to this. At the same time, the thought that he was quite handsome crossed my mind for the first time. He reminded me of those handsome Portuguese men.

I bet you know why I wanted to talk to you, he said, looking at me in the eyes. His eyes were peerless, and not at all unattractive. No, I lied, I have no idea whatsoever. He laughed and made an attempt to catch my hand but I thought that propriety demanded that I resisted his effort. He did not seem put out in the least. I will record the conversation as faithfully as I remember it.

‘I am not complaining, girlie, but it’s a lonely life here.’

‘Yes, Mr Malpas, I can believe that.’

‘Why don’t you call me Elias, eh, Fanny.’

‘Sure, Elias, I will do that.’

‘I will not beat about the Aussie bush, we don’t have too much time left. You know I am hitting the trail tomorrow.’

‘Yes, I was sorry to hear that you cannot stay longer.’

‘You mean that, don’t you?’

‘Of course I do, Mr Malpas.’

‘Then I’ll have my say without any further ado.’

‘Sure, I like that in a man.’

‘Ever since Georgie boy asked me over, saying his sister from home was over, I have been thinking of you… I mean you and me… how does that hit you?’

‘I don’t know what to say, eh… Elias.’

‘Say yes. Please say yes.’

‘Well, yes, but… eh… yes to what.’

‘I didn’t know I was so shy, girlie.’

‘Just say it…’

‘Well it’s like this… I haven’t been with a woman for a whole year, would you believe that. What I am saying is… how about it?’

‘It?’

‘Why don’t you hop in ’ere Fanny… there’s enough room for both of us in this goddam bed for Christ’s sake!’

I thought that I’d die before I let him see my tears, and I left the room without banging the door.

Twenty-eighth of December 1846. I resolved to say nothing to dear George. It was definitely not his fault. How was he to know what sort of man Mr Malpas was? But I cried buckets that night. I did not even like the man, and I let him humiliate me. I felt soiled and betrayed and cursed myself for betraying the memory of my poor dead heroic Quentin. I carefully avoided his gaze but could not help noticing that he had a perpetual sneer on his wicked face thereafter. When he left shortly after, I put on a brave face, and saw him off, shaking his slimy hand in the bargain, as I did not wish dear George to feel he had been instrumental in causing me grief.

Third of January 1847. After the ordeal that I went through, I wanted away from this place, but to my amazement, before I intimated my wish to George, he asked me into the small office where he did his accounts and planning away from his women. He told me that his dearest wish was that I would stay in Hunter’s Valley with him, but he knew that I aimed to go back to Stroud. He asked if he could ask me for a big favour. He and Amelia had often worried about Annie’s education. The poor girl had been short-changed, living in the outback, and they would be failing in their duty as parents if they did not try to remedy this sad state of affairs. He had often marvelled at how well Annie and I got on with each other, and wondered whether I would acquiesce to taking Annie with me when I went back, let her stay for a year in a civilised town, be her mentor and guardian, and perhaps do the right thing to see that she meets some eligible young man, preferably someone without too much to keep him in England, and who would welcome the challenge of Australia, where if he set about it properly, he would have every chance of hitting gold. One has got to give dear George credit for his clarity of expression and for going straight to the point. I was overjoyed, for everyday my affection for Annie had grown and grown. She and I got on very well, and I suppose I like the idea of being a surrogate mother, since any likelihood of my ever being a real one seemed to have evaporated in the glare of my silver strands.

Photo Credit:

RMS Britannia, 1840 (public domain)

Photo Credit:

RMS Britannia, 1840 (public domain)

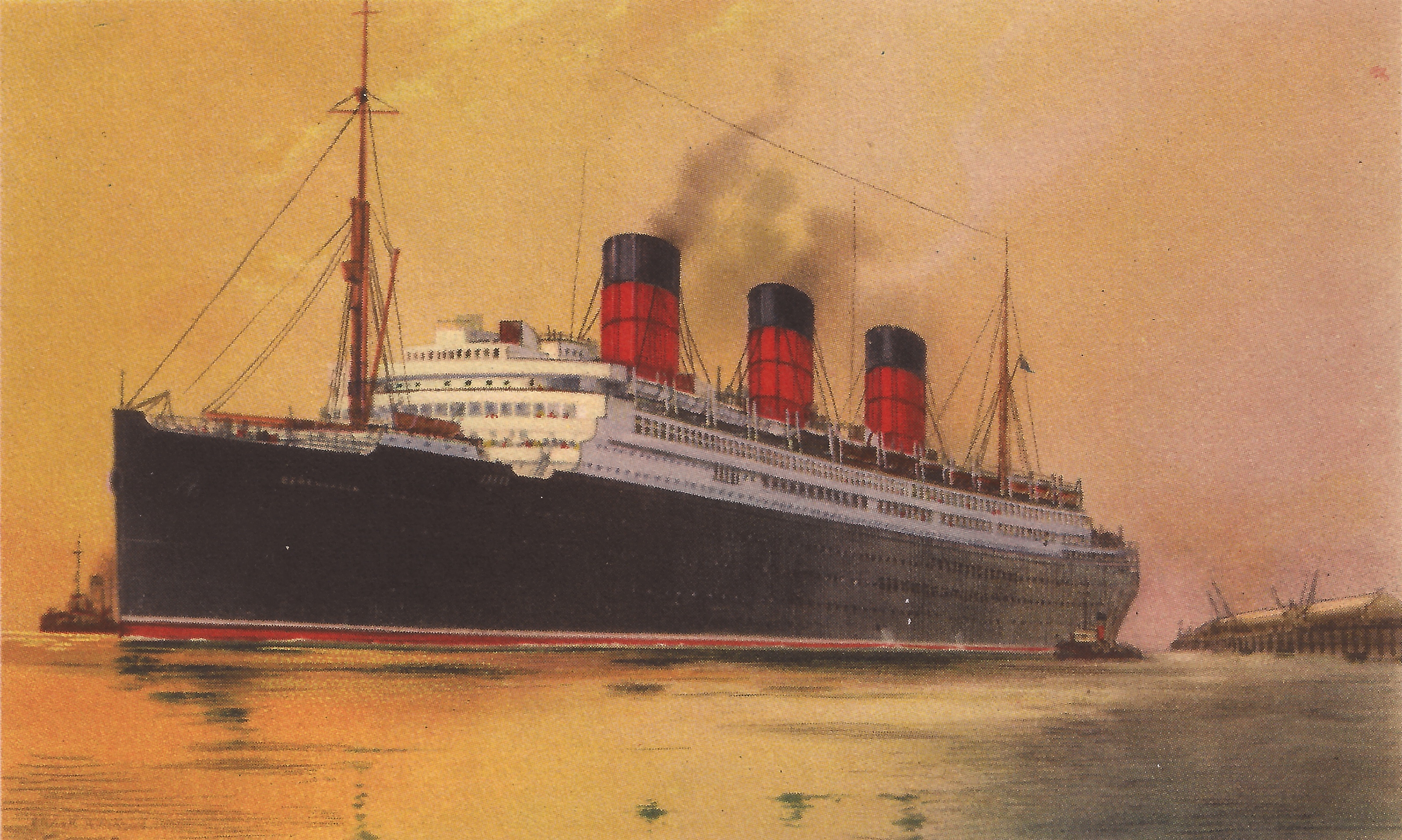

Twenty-first of February 1847. Now that we are on board the steamship SS. Wilberforce, with the prospect of six weeks at sea, I have decided to come back to my faithful journal. Apologies, dearest friend, for neglecting you, and for nevertheless seeing the welcome on your frank and open page. This is one of the newest steamer built and one of the first to do the Liverpool - Port Jackson route. It is much more luxurious than the clipper and the cabins are much roomier. There is a comfortable saloon where one may spend time reading and writing peacefully, and indeed that’s where I am now. We left this morning, on a southerly course, and the country seen from the ship is absolutely amazing. Annie is so excited, and I envy her the optimism of youth. The dear child thinks that nothing bad can ever happen to her, and I am pleased for her. Harsh reality will dawn upon her soon enough, so let her enjoy life until such times as she loses her rose-tinted spectacles. She is quite exhausted by the excitement of the preparation, and is having a prolonged nap. I own that I find her good-natured excitement quite exhausting too, at times.

Twenty-second of February 1847. Yesterday I had to end my entry abruptly, because of a most wonderful apparition. As I was busy writing my diary, alone in the saloon, I became aware of a presence, and on raising my head, there he was. The finest young man I have ever cast my eyes upon. He smiled as our eyes met, and with a bow took a few steps in my direction. He begged to be excused for his impertinence in daring to address a young lady on her own, but assured me that being discourteous to me was the last thing he intended. Did he have my permission to continue this intercourse, or should he just bow out? I felt weak at the knees and trembling all over, I invited him pray to tarry. He introduced himself, Captain Percy Robertson, late of the 23rd Regiment. My heart missed a beat when I heard that he was from the same regiment as my dear Quentin. He noticed how I had turned ashen on hearing this, and asked what the cause might be. Tears started rolling down my cheeks, but I took a deep breath and composed myself and told him about Quentin. The legendary Bell-Mowbray! he cried. I had the honour of knowing the dear man. What a hero! He had of course only been a green non-commissioned officer himself, he owned, but he was a participant, albeit a minor one, and a witness. When historians will write about the capture of Sind, he said, they will wax lyrical about Napier and Outram, but I will tell you that we who were there will never forget Tew and Bell-Mowbray! You are making me cry, Captain Robertson, I managed to blurt out in spite of the lump in my throat. I invited him to sit down by my side, and the two of us just sat there not saying much at first. Then he questioned me, and I explained that I was going back to Stroud taking my young niece with me. He told me that his father, was the famous Sir Rob Rob Robertson of whom I must surely have heard (I had not, but nodded) Percy had been visiting him in Penang, where he runs one of the most important companies in the colony. His father wanted him to resign his commission from the army, as he had plans for him, which he would prefer not to bore me with. To cut a long story short, we seem to have become fast friends, and he made me promise that I will allow him to come talk to me tomorrow. He had a few businesses to attend to with the purser and begged my leave. I breathed a sigh of relief as he left, not because I wished him to go, but because the tension had become unbearable, with this most excellent man sitting by my side. I had originally thought that he must have been quite young, but at some point he did mention that he was just a few months short of thirty. I am twenty nine! Oh stop it Fanny, one does not lie to one’s journal! I was thirty one last month. I wonder if he would not expect a much younger sweetheart. If I have struck gold, as Annie says, might he not overlook my being a few months older?

Twenty-third of February 1847. I confided in Annie that I had met a wonderful man, that night, and she declared that she was impatient to meet my beau (her description). He is nothing of the sort, I exclaimed, I have only talked to him for half an hour, I know nothing about him, but you are right, he seems like a very nice young man. Why did I have to add what was not even true? And for all I know, he must be years younger than me. Why are we of the weaker sex so defensive about our feelings and seek to deny them? So this morning, when we were strolling on the deck, as we were both spared the inconvenience of sea-sickness, as if on cue, Captain Percy appeared. Annie let go of my hand and fairly jumped towards him, greeting him in her usual ebullient manner. ‘Oh, Captain Robinson, my aunt told me so much about you. I couldn’t sleep a wink last night, for wanting to meet you.’ The Captain was slightly taken aback, looked at me, but seeing no disapproval on my face, he relaxed, and let himself be taken by the hands. Arm in arm they made towards me, and we found ourselves deck chairs on which we reclined, watching the coastline of Southern Australia disappear in the afternoon mist. I was delighted that Annie was so fond of my Captain, as I had already begun to think of him. I am sure that when I met Quentin the first time, I experienced no emotions as strong as those I was already feeling for the man. I was delighted that he and Annie were getting on so well. She would therefore give a good account of him to George when she wrote to him. Annie questioned Percy about his Indian campaign, and he was only too pleased to recount his many adventures, and I was struck by his playing down his bravery and heroism, although I am sure that he was just as heroic as my Quentin. We thoroughly enjoyed the day.

Twenty-fifth of February 1847. I cannot, must not blame Annie! She had obviously experienced what the French call the coup de foudre. Dear Aunt Fanny, she asked me that night as we were preparing to go to bed — I had forgotten to mention that we had a two berth cabin all to ourselves — you cannot not have fallen in love with Percy, you must tell me if you have. I laughed. Of course not, gel, I told her, love is not something you walk into blindly; for all we know the man may have a wife and three children already; he never said. Annie’s face changed colour visibly. Don’t be horrid, she said, he can’t have. We said nothing for a while, each engaged in putting on our night dress. As long as you have not fallen in love with him, she said negligently. Of course not, I said, I am a wise old bird with a sound plumed head on my shoulders, I said, recognising the falsehood of my tone and knowing that the innocent Annie did not — or perhaps chose not to. She fairly jumped on my neck, hugged me and kissed me, after which she uttered the saddest words that I have ever heard in my life. Because then, she said dreamily, I am resolved that I shall become Mrs Percy Robertson! Don’t be silly, I heard myself say — the most futile exercise ever in locking a stable door after the horse had bolted — you are too young to fall in love anyway; you are just imagining that you have fallen in love with a man we do not know from Adam. Remember looks are often deceptive, I said, repressing my tears. But Annie was not listening.

Yesterday I had a violent headache all day long and did not venture outside the cabin. When Annie came back after supper, she was brimming with joy and excitement, and explained to me that Percy had eyes only for her, responding with cold courtesy to the obvious seductive attempts of the Misses Watson, Proudfoot (she called them the Proudfeet), Amberson, Delaney and others. She was sure that he had fallen heads over heels in love with her too. I prayed to the good Lord to give me the fortitude and forbearance to deal with this calamity. Yes, dear diary, I cannot hide it from you. Had I played my cards right, Percy Robertson and I would… no, I cannot say it… it’s too painful. I had to tell myself that the Lord must not have willed such a union. Thank you God, for all your munificence, may it extend to making me understand how you arrive at your decisions for us.

Twenty-eighth of February 1847. Sweet dear lovely Annie. Until today, I always thought that she was an over-indulged woman child, and I will even own to still despising her a little bit while at the same time having genuine love for her. Maybe I should also admit to slight jealousy towards her, perhaps even a little anger for being blind to my true sentiments. Yes, without her, I might easily have landed myself an admirable man; we had had the most propitious start imaginable. But clearly the good Lord did not wish it to happen. She went full tilt, as she said, and ensnared the desirable Captain into a weave of her charm, insouciance and beauty. She is undoubtedly as pretty a young lady as can grace the most distinguished salons of Knightsbridge.

Auntie Fanny, she asked me suddenly this morning — I had slept very badly last night, because I was gnawed by my conscience, and without meaning to, I had been sulking at her, although I tried to conceal this, but I pricked my ears at this point. Yes? dearest. I have an idea that I might have done something to incur your displeasure, she said. Why do you ask? I was thinking that I might have done you irreparable harm. Me? I asked. Don’t be silly, how could you do me any harm? I said, still not sure whether she was referring to my initial infatuation with the dashing captain — yes I admit it, it was infatuation. She elaborated. She believed that she may have selfishly and unwittingly stood in my way to happiness, that Captain Robertson was smitten with me and that she had stolen him from me. I burst out laughing and assured her that nothing was further from the truth. My outburst sounded so false to my own ears, but Annie is a child, innocent of the way of the world. Are you sure? said the dear child, because I swear that I can give him up, if that will make you happy. No, I said forcing a controlled laugh which I tried to make as genuine as I could, why would I want your Captain Percy, when my own John back in Stroud is all I want. I was just as surprised as dear Annie on hearing these words. John? she asked, why Aunt Fanny, you are one dark horse, we never knew. Do you mean your trusted manager Mr Merryweather? I knew it, I knew it! Who else, Annie? But I made her swear silence on the subject, and she was as happy as a lark on being made my confidante and at the same time greatly relieved that she was blameless as far as Percy was concerned.

Now I do not know how I am going to spend the next 5 weeks, pretending that all I am waiting for is to be reunited with “my” John, whose face as I write this, I cannot even recall, although he is indeed a most admirable man.

Tenth of April 1847. It was a tour de force, living a lie for five weeks, pretending that I was basking in the reflected happiness of my niece and her new love and at the same time counting the minutes to my reunion with “my” John. I have too much pride to risk a rebuff, for I fear that even if Annie were to drown her infatuation in its infancy, Percy would not necessarily come back to me. I was definitely too old for him. So I played the game, Cupid’s game, listening to Annie’s confidences, advising, helping whenever I could. I must admit that Percy was no fool; every time our paths crossed, he acted like a man who thinks he has been guilty of a betrayal. He tries to look away or if he could not engineer that, he would blush uncomfortably. But why had I mentioned John Merryweather? Could it be that deep down I had always nurtured some secret affection for the man? I know that there are few men I respect more. His wife died five years ago, but I had never envisaged the possibility of us two being together, after all we come from different strata, John’s father was a mere tradesman, though known for his honesty and straightforward ways. Still ‘my’ Merryweather is worth ten Elias Malpas. He is as honest a man as breathed God’s air, has a pleasant face and bearing, charm and wit. I daresay that his lowly station put aside, he would indeed make an excellent prospect. There, I have said it.

Now we are due to arrive in Liverpool in a couple of days. Percy has sounded me about a possible engagement between the two of them, and has even said that he realised that Annie was too young, but has given me his word as a gentleman that he would wait for her for a year or two. I said that I would write to my brother giving him my favourable opinion of him. He dutifully kissed my hand in thanks. Annie was heart-broken. Dearest Auntie, she entreated me, tell me how I am going to endure being separated from the man I love for so long. I laughed and said that we always manage. I love you so very much, dearest Auntie Fanny, you are such a brick, and I wish you every happiness with John Merryweather. I fear that Annie is going to drop a big brick which might make it awkward between me and my manager. A good manager is as rare as gold dust, I daresay.

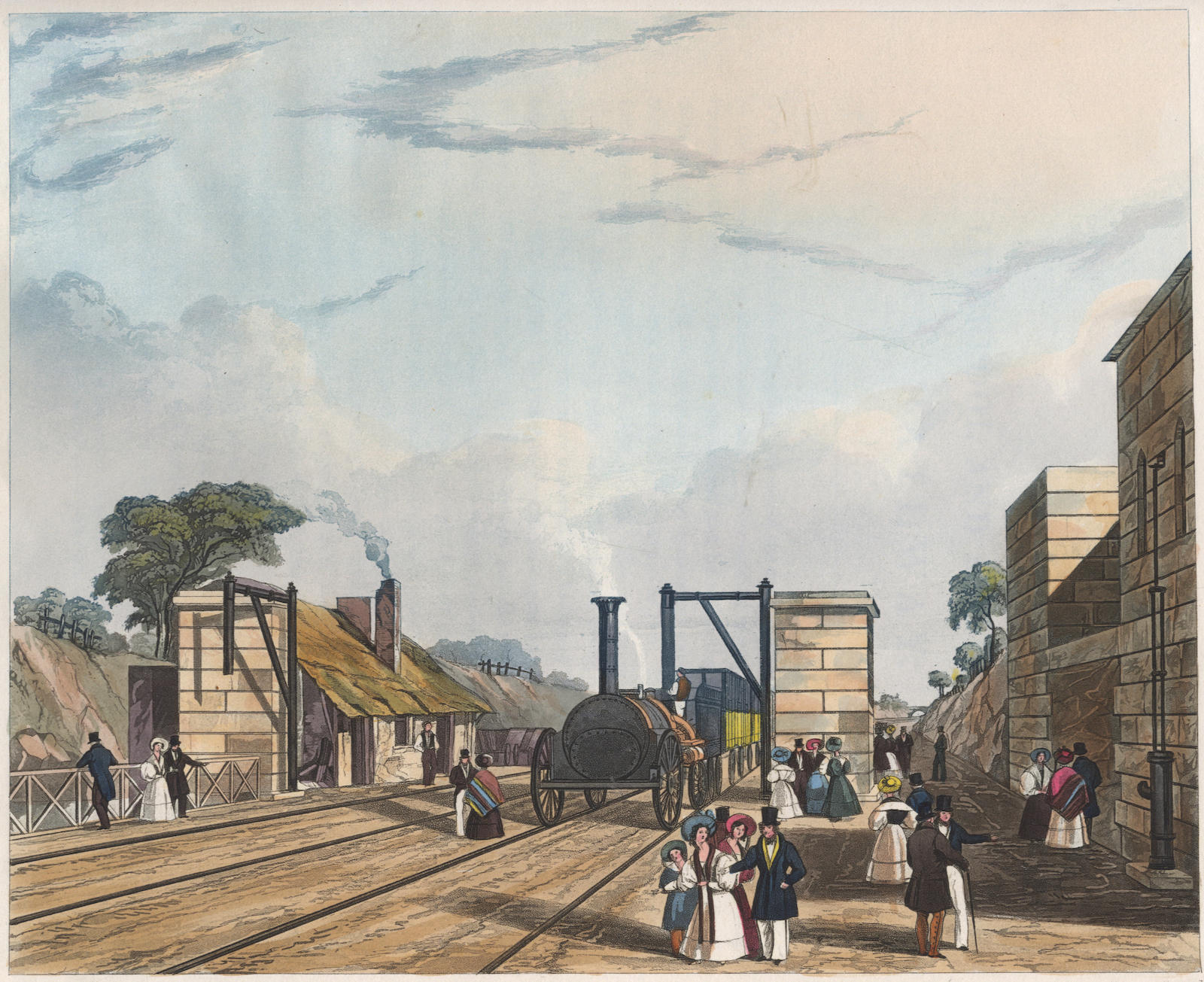

Thirteenth of April 1847. Percy has told Annie that he was going to the Foreign Office in London, where he was to be appointed aide-de-camp to a colonial governor, although he had no idea where, and we took our leave. Merryweather had booked seats on the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway from Liverpool for us, and his telegram had indicated with his usual precision, where to change. Finally we are to catch the Birmingham & Gloucester Railway, when he will be waiting for us in the fiacre for the final ride home to Stroud. I have had to swear Annie to discretion concerning the imaginary romance between me and dear John.

Photo Credit:

plates by S.G. Hughes and H. Pyall after T. Bury, plates watermarked "J. Whatman, 1831" (Public domain)

Photo Credit:

plates by S.G. Hughes and H. Pyall after T. Bury, plates watermarked "J. Whatman, 1831" (Public domain)

Nineteenth of May 1847. Whatever possessed me to blurt out that big lie about me and John? Annie would be discreet if she knew how, but she has an impish temperament and the wonder is that John did not immediately gather by her looks and complicit smiles that something was afoot. Then the poor fellow started exhibiting signs of confusion in our daily intercourse. The relationship between the two of us is now more than a bit strained, and John feels threatened, no doubt thinking that he as done something amiss. I cannot find a way out of this self-inflicted contretemps.

Tenth of July 1847. The professional relationship between John and me is becoming more and more strained, and I could see that the poor man is not happy. Still I did not expect it when yesterday, he approached me with his usual forthrightness.

‘Ma’am,’ he said, ‘I will be obliged to you if you can find the time to hear something I want to say.’ My stock response under similar circumstances is, sure, Mr Merryweather, there is no time like the present time. We sat ourselves, me at my desk, and he on a plush chair reserved for visitors. Yes, I said, I am all ears.

‘Well, it’s like this, ma’am,’ John was not one to dilly dally, ‘I have felt for some weeks now, ever since you came back from Australia in fact, that I am no longer giving satisfaction in my work.’ He paused, expecting me to say something, but I was too dumbfounded to speak, so he carried on.

‘If you want me to go, you must say so, and I will go without fuss, but in all fairness, ma’am, I must ask you to give me specific examples of the ways in which I have erred or been remiss.’

‘No,’ I said, ‘you have not been remiss in anything, I swear,’ but I was unable to say more, because I was debating with myself about what to say. The man had served me efficiently and faithfully, and I could not tell him that he had imagined the strain in our relationship. Did I owe him an explanation? A white lie had led to this uncomfortable situation, and I said to myself that I was not going to cover its ill effects with another one.

‘Am I then to take it that I have imagined the…’ the poor man was stuck for words.

‘Cooling off in our intercourse?’ I said. He smiled. I recognised that smile from a dozen similar situations in the past. It meant, you always know the right words, ma’am.

‘There has never been any cooling off, John,’ I said, possibly the first time ever that I have preferred that appellation to the more formal Mr Merryweather. I hoped that he would accept this and that would be the end of the matter, but he was not the sort of man who would accept an anodyne reassurance.

‘But ma’am, I cannot see that there has never been a cooling off, I am sorry, but you always liked frankness.’ I resisted the temptation of saying that I had no more to add.

‘All right, John, it was a little silliness on my part if you must know.’

‘Ma’am?’ he said and stared at me, dumbfounded. My admitting to silliness seemed to him like the pope in Rome owning publicly to fallibility. He stood up, and was on the point of bowing and leaving, when I heard myself speak.

‘You see, my niece Annie… when we were travelling home from Australia on the Wilberforce… Annie started teasing me about what she thought was my infatuation with Captain Percy, with whom she is now officially engaged. When I knew they were smitten with each other, and not wanting to stand in their way, I mentioned that my heart was otherwise engaged, and belonged to another… eh… and I… eh… took your name.’

‘You said that?’

‘Yes, John, I did; I do not know why.’ He blushed and started stammering incoherently, then took a deep breath, looked at me in the eyes, and I felt hot in the face.

‘Obviously you did not mean it, and that explains why you have been uneasy in my company ever since… I see.’ I nodded sadly.

‘Well,’ said John, ‘I would not want to be a source of embarrassment to you, and let me assure you that I do not for one moment think that I have been ill-used. I will go as soon as you have found a new manager. In fact I will help you find one.’

‘John,’ I implored, ‘no, don’t go, dear friend, we are grown-ups and now that we have cleared the air, I am sure that we will be able to resume our former intercourse as if nothing happened.’ He said nothing for a while.

‘You mean… you were infatuated with the Captain, and when you saw that Miss Annie…’ he could not finish what he wanted to say, and shook his head wistfully. Then he raised his head and looked at me in the eyes, shook his head gently. ‘I have always known that you were a lady of exceptional selflessness.’

I could not say anything, and felt that if he said any more, I might not be able to hold my tears inside my eyes.

‘I have always admired you…’ he said, ‘much more than admire really, even when my dear Olivia was alive… only I never dared…’

Tenth of March 1855. I have not found time to make entries for a variety of reasons, but mainly because of all the change that has happened in my life. John and I have been bounced into a romance, because once I had told that lie to Annie, there was no way of preventing its inception.

In the intervening months, things had developed very fast, and to cut a long story short (it is not my story, so I can choose to cut it short), the sound of wedding bells is in the air. The wedding ceremony is to be held in Wells Cathedral, and the celebrations in Marchmont Manor. The illustrious Rob Rob, a youthful friend of the late lamented Shelley, Annie tells me, is coming over with Percy’s mother, and so are dear George and Amelia. They are all going to lodge with us at the Manor. Percy has been appointed aide-de-camp to the governor of Nova Scotia, and once married, the couple are to start their married life in the colony.

Nineteenth of November 1848. I received a letter from Nova Scotia this morning from Captain Robertson, informing me of their joy in becoming the proud parents of Rosalind, a healthy and angelic little baby girl. Dear Journal, I own to a joy not much less than theirs. Our own little boy, Edward Merryweather was born six months earlier of course. John and I daily thank the good Lord that He is watching over her.

Post Script. Rosalind Robertson and Edward Merryweather were married in July 1867. Their daughter Ann married George Robertson, a great grandson of Catriona Robertson (aka Wahaitiya) one of Don’s ancestors.