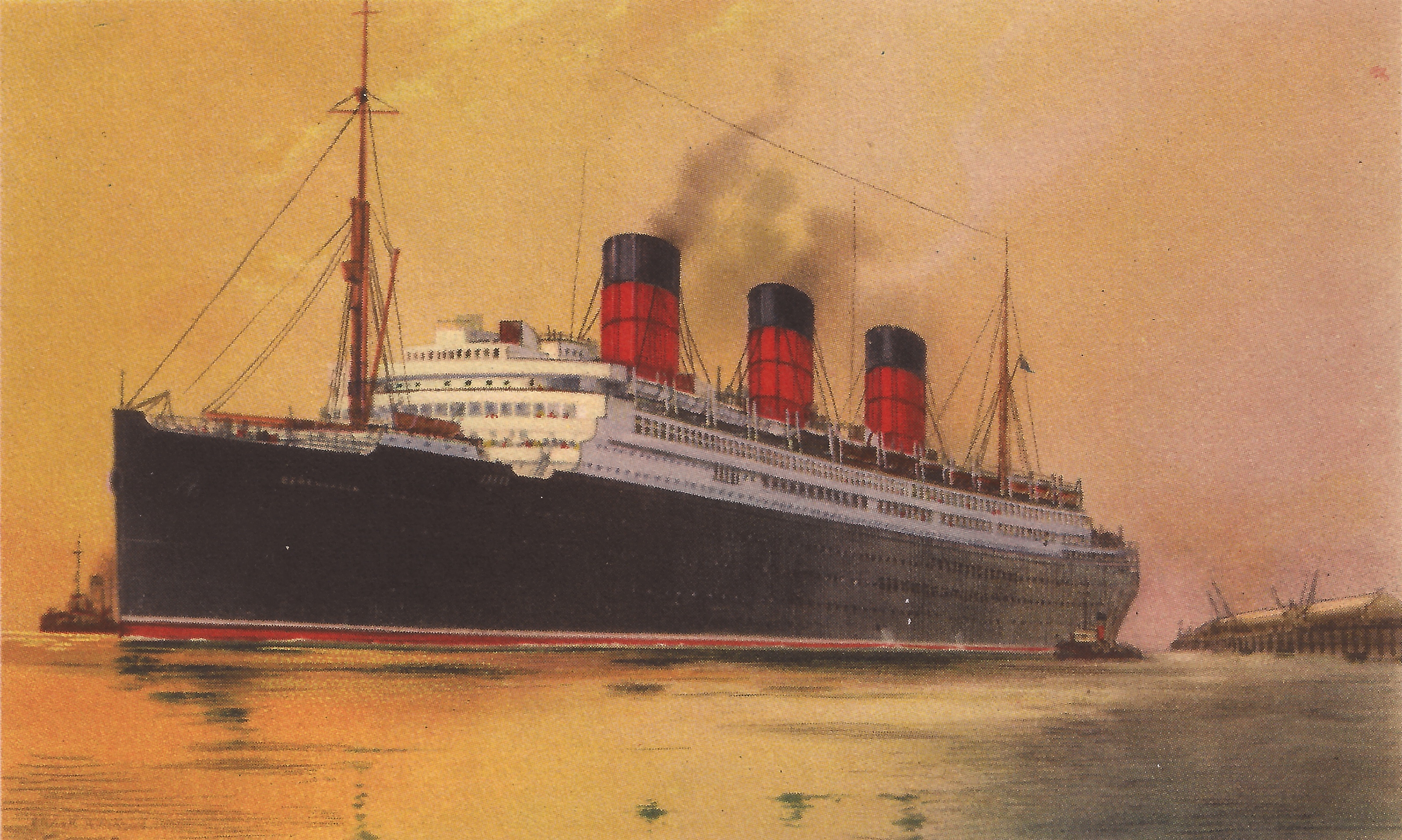

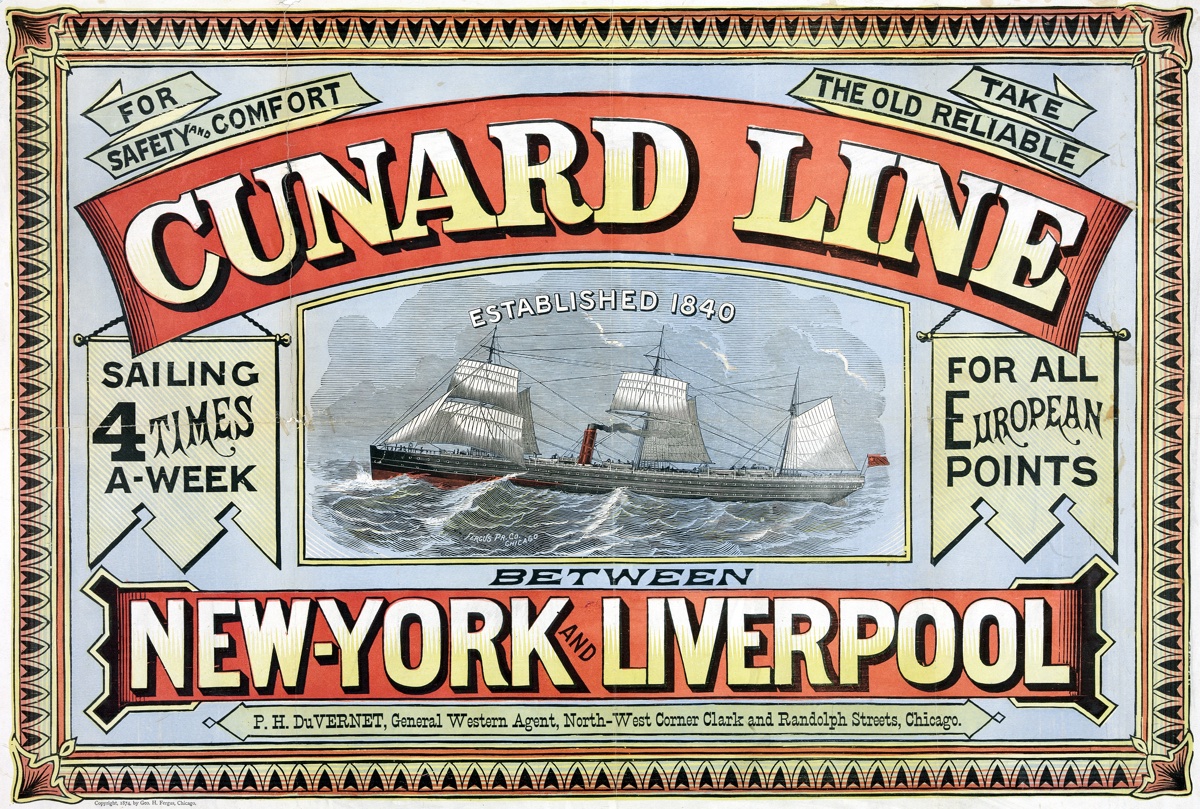

When Donald Robertson finished university in Cambridge with a first class honours in Natural Sciences, he booked his passage on the Scotia, the latest Cunard liner, an iron-clad paddle steamer which was leaving Liverpool bound for New York on its maiden voyage, due to reach Toronto in good time for Granny Kitty and Grandpa Wahaitiya’s diamond wedding, which was to be celebrated in the hall of the Highland College for Girls in Peterborough which Granny had created, to provide for the education of mainly Ojibwa and Cayuga children, although it was open to all.

The voyage was smooth and uneventful, with only the presence of an iceberg some distance away, causing a danger warning, breaking its monotony. Donald was not used to sitting in a deck chair for hours, but he had little else to do for the sixteen days the trip was scheduled to take. He sat on the deck, reading the many scientific journals that he had bought before leaving Great Britain. He never tired of reading and re-reading his books and papers. With his interest in birds, having studied zoology for four years, he found Thomas Bewick’s A History of British Birds with its wood engravings and its accurate observations, completely engrossing. He hoped that he would make an enlarged copy of Mr Bewick’s green finch one day, but on this ship, although he had time aplenty, his stock of material was packed in his many suitcases in the hold. He wryly told himself that in other times, he would have all the materials handy, but never the time. He wondered why he had bought The Illustrated Book of Canaries and Other Cage-Birds. The very idea of caged animals revolted him. The Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoological Society Delineated was a serendipitous find at Maggs, and he treasured this book above all else.

He never really liked tobacco, but a pipe gave him something to do, as he immediately started blushing and blinking at the approach of someone he did not know well. Fiddling with a pipe and a match gave him the means of minimising his embarrassment, and besides, this added a modicum of gravitas to his youthful appearance, his carefully nurtured moustache not helping much. He had contemplated growing a beard too, but as he was rather proud of his square jaw, he decided that he was not going to hide it.

Having always been bookish and withdrawn by nature, he had never developed the art of talking to the female sex. Why, he thought wryly, he hardly knew how to talk to men. He probably did not have conversational skills, for even when he talked about things of universal interest, like the behaviour of birds under different climactic conditions, (who can find that fascinating subject other than stimulating?) he found that after less than half an hour people began losing interest, and the same people, he noticed later, seemed singularly engrossed in something else when he appeared.

There were some handsome specimens of the female sex on board, and he easily imagined himself enjoying their company, but he had no idea what to do after you bowed to the young lady, smiled and exchanged information about the weather. He had promised himself that he was going to try ever so hard on this trip. He had the feeling that luck was on his side with so many desirable young maidens confined to the limited space of the decks and dining rooms. Propitious conditions indeed!

As he was reclining on a deck chair reading his Bewick, a young lady holding a fetching parasol, Miss Hilve Mortensen, to whom the captain had already presented him, and her aunt, appeared on the deck, walking towards him. He put his book down and looked for his pipe. He put it in his mouth and found a box of safety matches, in readiness. She was an American whose father had come over from Denmark and had bought a foundry in Boston. She had bouncy, bright, volatile blond hair and smiling blue eyes to match, a fine slim figure contrasting perversely with the aunt’s short squat physique, and a self-assured bearing. Yes, he would not mind getting to know her. Romances were known to sprout on an Atlantic crossing, and Donald was ready. He stood up and bowed to them as they drew level with him.

‘Oh good morning, Mr Robertson,’ said the aunt, in a thick Danish accent, and the niece smiled angelically and bowed slightly. He wondered whether he should make an attempt to kiss their hands, but started blinking instead.

‘Yes,’ he said enthusiastically, ‘it is a good morning indeed.’ A little erudition might help create a good impression, he thought, so he added, ‘The wind seems to be blowing in a north-easterly direction, and the clouds over there, which you might think are of the altostratus variety, are in fact cirrus clouds. It would interest you to know that they only appear nearer because the air is clear… what I mean is that rain is unlikely, with excellent prospects of a nice clear day.’ But he did not wish to sound like a know-all. ‘Of course I may be wrong,’ he said convinced that he was not, ‘I am sure the captain will issue a weather forecast in due course, and I for one, shall be studying it with great interest.’

Photo Credit:

George H. Fergus, Chicago,1874, from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

Photo Credit:

George H. Fergus, Chicago,1874, from the United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

‘How very interesting,’ said the aunt in admiration.

‘Are you interested in clouds, Miss… Andersen?’

‘Mortensen,’ the girl corrected hiding her mortification.

‘The captain was telling us that you won a first class honours degree at Trinity,’ the aunt said, more as a rebuke to the young lady, than to impart the information to him, since he was already aware of it.

‘Oh yes, I did, thank you. You see, I specialised in fish and birds…’

‘Oh do tell us about birds, Mr Robertson,’ entreated the older Miss Mortensen, ‘I have always wanted to know how birds migrate. I am sure you clever scientists know everything there is to know about that.’ Don failed to notice the look of despair that suddenly appeared on Hilve Mortensen’s face.

‘Well, this is not as much of a mystery as people might think,’ he began. He was going to enjoy himself. He started by taking a deep breath and clearing his throat.

‘All the senses come into it,’ he began with gusto. The fair Hilve frowned. ‘Vision, hearing and smell of course… but only a week ago,’ he added without a pause for breath, ‘I read an article in Nature, and I found it very enlightening, to the effect that earth magnetism plays a big part. You see, the earth can be considered as a big magnet with two poles…’

‘I know,’ said Hilve in an attempt to pacify her aunt, who she knew expected her to greet the young men she thought of as good prospects with some respect not to say friendliness. ‘One at the north pole and the other at the south pole.’ Donald looked disappointed. He pursed his lips and obviously regretted having to contradict her.

‘Actually,’ he said, ‘the so-called north pole is not at the north pole per se, nor is the magnetic south pole at the south pole. That’s a very interesting subject too, and if you are interested I shall be delighted to elaborate.’ They said nothing, so he took that as a cue to continue.

‘When we say that the needle of a compass points towards the north pole, it isn’t exactly right, it only seeks the north pole.’ He was now in full flow, but suddenly he was invaded by less scientific thoughts. The Captain’s Ball! That would be an ideal occasion to gain further intimacy with the highly desirable young lady. He had to impress her, so he explained polarity in great details, and then remembered that it had all started with bird migration. The ladies began to fidget. No doubt like him, they were eager to get to lunch. Bird migration will have to wait for another time.

‘I hope you will be going to the Captain’s Ball tonight,’ he said, ‘may I be so bold as to…’ his courage failed him. He put the pipe in his mouth and started lighting it. Hilve frowned.

‘Mr Robertson, I think you should put some tobacco in the pipe before lighting it.’

‘Yes, quite… quite right…’

‘The absent-minded professor, eh!’ the maiden aunt cackled merrily.

‘You were saying?’ she was determined to keep the conversation going.

‘Aye, yes, yes… I hope to see you there… at the ball.’ Hilve smiled and curtsied and led her aunt away.

Hilve avoided the young scientist after having verified her suspicion that there was no lousier dancer in the whole world. Donald was a bit disheartened by his singular lack of success with the girl, but that was not the first time that his earnest efforts at finding a soul mate had failed.

Still, he was not one to let desperation take hold of him. In any case, he had always been in two minds about attachments, as he feared that his pursuit of knowledge would probably come at a price. He badly wanted to find a woman to love passionately and whole-heartedly, but would she understand that sometimes, when his attention was completely taken by some investigation, he would have no time for her at all? He knew for instance that once he had embarked on a study, he could think of nothing else, he forgot to eat lunch, he was up all night, and when people talked to him he did not hear them. All those women who he had unsuccessfully tried to court in the past, might even have done him a favour by not responding to his attention. Hilve Mortensen was a case in point. She was a society beauty, and if he married her, she would expect him to attend and organise balls and soirées, and he did not expect soirées and balls to feature much in a life devoted to learning. On the other hand, a scientist is nothing if he has a closed mind. He must be open to new sensations, perhaps it would not be too difficult to juggle a social life with the seeking of knowledge. Still he wondered if the fair Hilve was at all winnable. He would discover that she was not.

Nothing much happened on board that was out of the ordinary. There were no encounters with icebergs, the sea stayed uncharacteristically calm, and the Scotia reached New York a day early. He travelled by coach to Rochester and from there took a ferry to Toronto. He stayed two days in that city and then father and mother joined him on the trip to Peterborough in their fiacre. The family had an impressive town house in Peterborough, but also possessed huge chunks of land and property spreading all the way to the Rice Lake, where great uncles John Smith and Albert Robertson (né Wahaitiya) had joined forces some fifty years ago and created their flourishing sawmill business. He was pleased to find that so much had changed, the roads were now macadamised, making the trip smooth and pleasant. The family estate had grown quite considerably. Thousands of acres of forest stretching from the Rice Lake towards Peterborough had been cleared since he was last there, and golden wheat was everywhere. Donald, who had spent almost three weeks at sea, where the unimpeded view of the ocean stretched to infinity, as if nothing else existed on this earth, had a similar sensation when passing through the cultivated fields. It was as if the globe had been transformed into a golden ocean of wheat to the exclusion of everything else, causing waves as the gentle wind dispensed with its caresses. The family owned over ten thousand acres of prime land on the banks of the Otanabee River and they had been transformed into orchards by Uncle John Smith Junior. Smith and Robertson were still the most important timber merchants in the Maritime and had a very modern plant which employed over a hundred workers, mainly Ojibwas and Cayugas. There were any number of new edifices of varying size, colours and styles lining up the road from the town to the Lake, housing the large influx of people from the Maritime who had flocked in there to find work.

Photo Credit:

Ontario Dept of Mines, 1913

Photo Credit:

Ontario Dept of Mines, 1913

Of all his family, he loved Granny Kitty more than anybody else. Mother was undemonstrative — not that he ever doubted her love for him. Father was too absorbed in the business of making money to have time for him. He regretted that he only knew one way of showing how much he loved and admired his boy, which was to lavish huge sums of money on him, often buying him things for which he had no use.

Granny claimed that the return of her favourite person in the whole world made her feel ten years younger. She was now the most respected woman in Peterborough, and Grandpa Wahaitiya glowed with pleasure every time some newspaper ran a story of one of her many achievements. He had kept a scrap book to show Donald. Father was devoted to his old man, and often regretted that following advice from his accountant, he had changed his name by deed poll to Robertson, at the suggestion of Granny Catriona. When one is in business, a Scottish name would sound more trustworthy than the Ojibwa name that he acquired at birth. Granny Catriona, like everybody else in this world, he simply worshipped. For once father seemed not to regret leaving Toronto and money-making. He much preferred working in an office and had left the practical side of the family business in the hands of his younger brother Albert and the Smith uncles who relished that sort of thing. He was so proud of his son, and expected to spend some quality time with him, not that he would be able to follow what the gifted young scientist would have to say. He wished he could hear his son disown Mr Darwin’s heretical claims, but because he feared that he might not, he chose not to raise that issue with him. Granny openly broached the subject of marriage.

‘You know dearest, there was a time when I was not sure if marriage was all that desirable an institution. It is even easier for a man to avoid it, as man can have liaisons without the world judging him harshly. But when I decided that my lovely Ojibwa man here, was the only man I would ever want, my soul mate, and once I talked him into throwing his lot with me, I changed my mind for good. A good woman can make all the difference to your life, trust me.’

‘Granny,’ Donald said laughing, ‘you are preaching to the converted, I want nothing else, but where do I find such a woman… my soul mate, as you say?’

Granny walked towards him, took his head and buried it in her breast, and said, ‘They don’t know those hussies, what a prize catch you would be.’ He always marvelled at her plummy Highland accent which she had never made the slightest effort of getting rid of.

‘Just find me one, then,’ he said with a laugh.

Granny did not need to be asked twice. Yes, there was Eve MacKay who was teaching at the school, recently arrived from Greenock, Scotland, and who was boarding with the headmistress, Mrs Phillips. She will arrange for the two of them to meet, specially as she knew that Mr Phillips was going to be away in Toronto on business. She sent word to the headmistress who was a good friend, and got her to arrange for the two young people to meet. Donald was delighted. He was already half in love with the charming Scotswoman whom he had not even seen yet.

Mrs Phillips invited Donald and Eve to tea on Wednesday of the following week. Donald had spent a sleepless night putting some order in the subjects he might broach in an attempt to make a good impression. He obviously knew about fish and birds, but besides, he also knew a large number of useful scientific facts about volcanoes, hurricanes, astronomy, natural selection. So when he met Eve, he was positively brimming with facts and rearing to let them loose on receptive ears.

Eve was very pretty and had high cheekbones, lips which were thin but seemed to go on forever until they seemed to reach her ears, and a small snub nose. She was just the way he liked women, slim, not very tall, auburn hair coiled in thick tresses, and crystalline black and intelligent eyes. Most noticeably, she had a bearing that was elegant without being arrogant. With her slightly pointed jaw her profile had a fetching triangular aspect which made her possibly the most attractive woman he had ever come across. When Donald went to school, teachers had no right to be so pretty. He imagined that he could indeed easily fall in love with a woman like her. She talked softly but quickly, in a determined manner, and chose her words with great deliberation.

As he would have expected in a dedicated teacher, she thought that education was by far the most important thing in the life of a child, even more important than food or medicine.

‘Medicine has made fantastic progress in the last ten years. When I was in England, I —’

‘Without education,’ Eve interrupted, ‘no one would be able to learn medicine, and…’ He was not listening to her, but admiring the intensity and clarity with which she was putting across her views.

‘Of course most teachers do not choose the profession in order to enrich themselves,’ she said, ‘it is a vocation, or it is nothing!’ Don could hear the impact of the exclamation mark.

She went on without stopping, broached the subjects of morality and ethics, decried the obstacles standing in the path of women seeking to educate themselves. Did Donald meet any women students when he was studying at Trinity? No, of course you did not, because women are not allowed to go to university! He had the strange feeling that she seemed to be holding him personally responsible for this sad state of affairs. No, of course she did not hate all men, where would she be if her own dear father the Reverend Gordon MacKay had not undertaken to educate her personally?

He allowed his mind to wander momentarily, and when he urged himself to pay attention, she seemed to be holding forth about the necessity to educate adults, and was advocating the creation of night schools, not only for those adults who felt that they had missed out, but for anybody who was still illiterate or semi-literate. In her view, illiteracy was as great a calamity as consumption. Donald now stopped listening to her, and was just nodding, waiting for a moment when he might slip a word in edgewise. He found that whilst he might be in agreement with Eve, he did not necessarily want to know all the pros and cons of the matter. Good thing though education was — and he had no quarrel with her position — it was only interesting up to a point which Eve had overtaken a full two hours earlier. Seamlessly she seemed to have broken into new grounds, explaining why she thought that it might be better for children to start by learning simple words rather the letters of the alphabet. Eve seemed delighted with the way the evening had gone. She expressed her delight at meeting someone who obviously shared her passion for education and was so interested in what she had to say, and hoped that they might meet again.

Next morning at breakfast, Granny was all smiles.

‘Come on now, laddie, tell granny how the evening went. What did you think of Eve MacKay? Did the two of you hit it off?’ Donald pursed his lips glumly.

‘Well granny, I liked her a lot at first, I thought she was very pretty, intelligent and charming, but my God, what a bore! She talked about nothing but education all evening, I was never so bored in my life. Why won’t people understand that what they might consider interesting, may leave their interlocutors cold?’ Granny Kitty promised herself that she would try again at the earliest opportunity.

The big party for the grandparents’ wedding anniversary was a big family occasion, and everybody seemed to have a great time. Even great uncle John Smith and great aunt Felicity, who were on their best behaviour, seemed thrilled. They had always intrigued him. As a child, he could not help noticing how they could not bear to be apart, and surmised that few married couples could be so much in love, but they did not seem happy, there was always some tension between them which he could not understand. Later he discovered that John drank too much, and Felicity was given to bouts of depression. Granny Kitty who was not given to passing judgement on other people, once confided to him that although the great aunt was the one who had instigated the big romance, although she did not doubt for a minute that she loved her brother John as much as anybody could love a husband, she could never forget that she had married beneath her station, and instead of cashing the great love that they had for each other and building a happy life with it, she could not resist pointing out, even in company, how uncouth he was, always trying to change him so he would become a polished gentleman. Early in the marriage, Kitty had advised her brother to put his foot down and tell her to stop this nonsense, but dear John would never raise his voice to anybody. He so hated giving offence, that he much preferred to say nothing and bottle it all in. This, she explained was what had driven her brother to the bottle.

Father was due to leave for Toronto in the afternoon, and in the morning Donald and he had been locked in conversation in Granny’s study. The old man had made it clear that he had no intention of dictating to his son what he had to do.

‘I am proud, Donnie,’ he was saying. He was the only man who called him by that strange appellation. ‘I am proud that whatever my failings, not having followed the advice of Mam, and denied myself learning…’ Donald nodded, it was true. He had been a dutiful father, he knew how much he had loved him, even if he had not been the type to give him a piggy back or go for a swim with him. He was not always there for the momentous events in his life, because he had other priorities. What was better for the family that I love, he would ask himself, to negotiate that contract worth ten thousand dollars or to take the boy out kite-flying? Money was very important for one’s happiness, how can one say one loves one’s family if one left them unprotected from the vagaries of life? Thus he had never flinched from spending money on his wife, his only remaining son, his father and mother. He had spent tens of thousand of dollars building them that house in Peterborough. Would they have preferred him to neglect his business and visit them more often? No, a house was more concrete. Didn’t Donnie agree? He had never given this much thought, but he nodded.

‘Tell me, Donnie, have you made any plans for the future?’ He immediately added, ‘Mind you I am not pressing you, I know how hard you have studied, I had my informants, you know,’ he added with a smile, ‘You need a rest. Stay with your granny here for as long as you like, put some order in your thoughts, and I know you will arrive at the right decision. When you do, just let me know.’ Donald always felt a bit uneasy with the old man, but he knew that there was much unsaid love on both sides. He coughed uneasily and smiled apologetically.

‘Actually Father, I rested more than I needed to on the crossing, I don’t need a rest. Enforced idleness tires me out.’ A chip off the old block, the old man thought happily. He too found holidays tiring, which was why he rarely took one.

‘I propose to set to work straight away.’

‘Are you planning to secure an appointment at some university? With your Cambridge degree you should have no difficulty at all, I daresay. I know one or two good people who will put in a good word —’

‘Father, I am not planning to join any university at the moment, I want to… Oh, I don’t know how to put it.’ Old Mr Robertson frowned, he liked straight talking.

‘I want some hands-on, eh, I think that’s it’s called now, hands-on experience first. The last four years I have almost always been between four walls learning from between two covers, occasionally dissecting birds and rabbits… what I want to do now is to go out in the wild and learn first hand from nature.’

‘I am not sure I understand what you’re saying, Donnie.’ The young man cleared his throat.

‘If you are agreeable to my proposition, I would like to go live in places where I might come in contact with fauna and to some extent, flora. Birds, fish, rare animals and plants, make a comprehensive study of them, photograph them, make sketches of them, that sort of thing.’

The old man stared at his son, not sure about what he had heard. Suddenly his face lit up.

‘This is the ideal country to study bears and…lichens… ’ He did not finish the sentence as he had caught Donald shaking his head.

‘Why Donnie, you know best… Draw up a plan of action and we can discuss the financial aspect.’

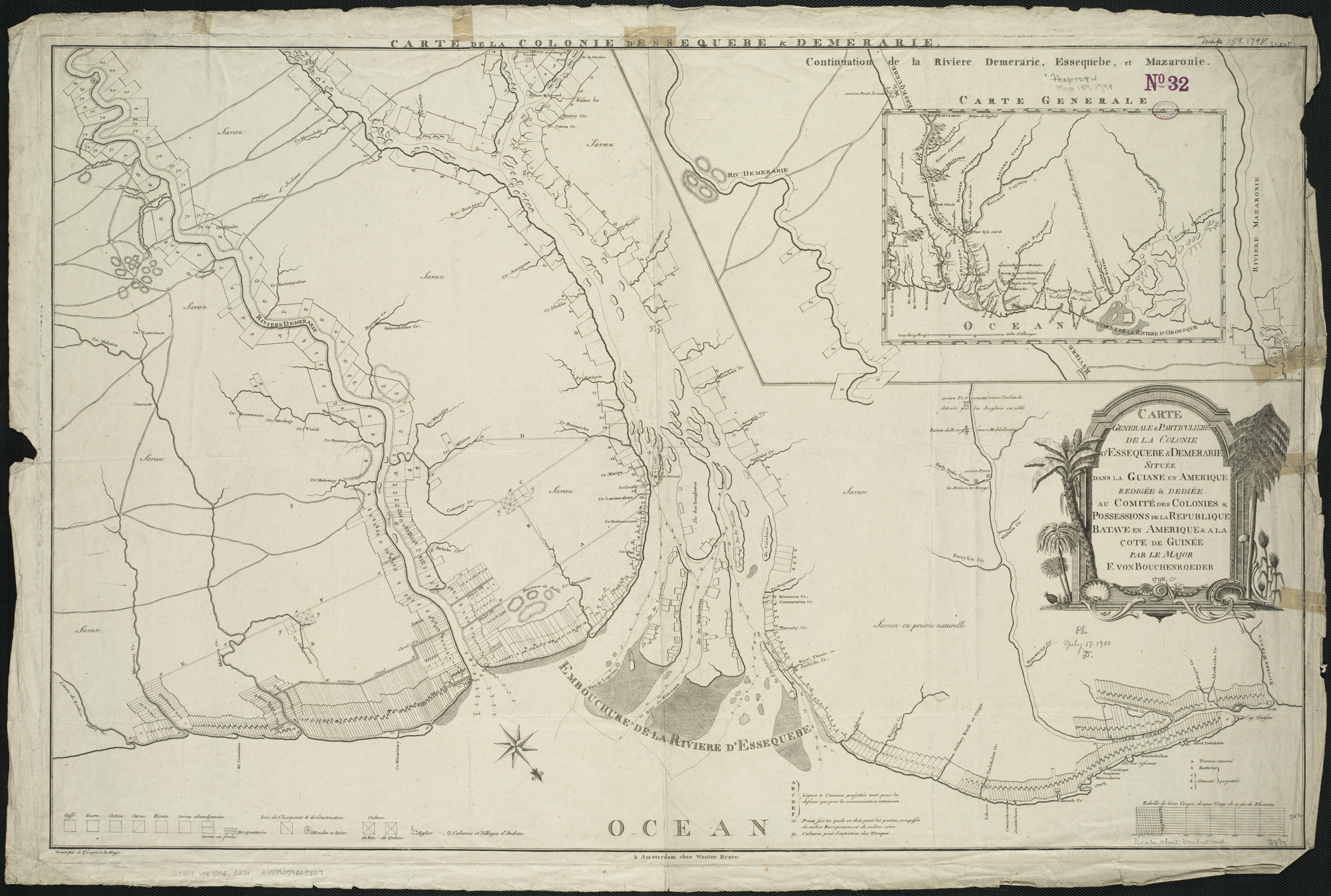

Donald had already thought everything through. He would like to go live in Demerara for a while. The land there had, density-wise, a richness of fauna that had no equal in the known world. He would set up a base there, then make trips down the Demerara and the Essequibo rivers, study the land, the birds and the fishes, and then possibly use his findings towards a doctoral thesis. He thought a year there would do for a start. The old man said that he would arrange for the equivalent of one thousand pounds sterling, in Spanish dollars, to be put aside for him straight away. Would that be sufficient? One thousand pounds? I could buy half of Georgetown with that.

Photo Credit:

Brave, Wouter, 1798

Photo Credit:

Brave, Wouter, 1798

Madeleine Rose Robertson was disappointed about her son’s hurry to leave after having been away for so many years. One week in Peterborough and then three in Toronto. He had to know how she adored him and how dearly she would love to look after him. She knew that people would find her ridiculous if she told them that the thing she missed most in life was helping her son putting his shirt on and combing his hair when he was a child. She knew that Donald would not like it now, but how she wished that he would let her, hold his head against her breast and rock him to sleep — and comb his hair — just once. He had grown up far too quickly for her. She vividly remembered the day the doctor confirmed that she was with child; she remembered his little half-formed feet kicking her, like it was only yesterday, and look at him now, he was almost twice her size. When her first born Graham died of meningitis, she thought that she would never recover, and had resented becoming pregnant gain so soon after. She was unsure about loving this newcomer whom she thought of as an interloper coming to take the place of her little angel, but the moment she heard his first cry for help, all the bottled up love for the dead child rose to the surface again and took over her whole life, like a drop of oil poured over the sea is known to spread over it for square miles. And now he was going away again. She had read about Demerara. There were primitive tribes there, cannibals, an article said, and dangerous animals, jaguars and venomous snakes. She would worry about him all the time and would never sleep again at night. Why couldn’t he break a leg and be house-bound, so she could look after him? Not forever of course, but for a year only? That would be heavenly… No, she was being selfish and undignified. She could only hope now that nobody would uncover that wicked thought of hers.

‘Donald dearest, have you not thought of starting a family?’ Maybe it was not too late to make him change his mind. She knew about mother-in-law Kitty’s unsuccessful attempt but no one had told her the details.

‘To start a family, Mama dear,’ the son replied, ‘one needs a wife, and I don’t seem to have one.’ She knew that he was not being facetious, he was sometimes very opaque.

‘Oh a boy of your… gifts… will have no difficulty finding a good woman… there are hundreds of eligible young women —’

‘I will come back in a year’s time Mama, and I daresay some of these wonderful young ladies will still be around, don’t you think?’

‘We missed you so much, your father and I, we counted the days.’ Donald knew that he should say that he missed them too, but he had not, so taken up was he by his studies, so he kept quiet. Madeleine’s face lit up, she had yet to play her trump card.

‘Your gran so wants to have you around, she is getting on, you know.’ This did produce an effect on him. She always knew that the boy felt more at ease with the old dear than with herself, but jealous she was not. At least she hoped not.

‘Oh yes, granny Kitty… but I will spend a whole week in Peterborough before I leave.’

‘She will like that,’ she conceded, ‘yes, do go visit her.’

‘And I will spend at least three weeks in Toronto with you before I leave.’

‘So your mind is made up?’ He pursed his lips and nodded.

‘I will write, Mama,’ he said, ‘to you and father,’ he added, remembering that he seemed to write only to Granny when he was in Cambridge.

‘Yes, dear, write often, we so enjoyed your letters.’ She did not tell him that she had read all his letters so often that she knew them all almost by heart. She probably could give a better account of what he had done those four years in the old country, than Donald himself could.

From Toronto he went to Montreal down the St Lawrence, and from there father, who transacted business with the Booker brothers, had arranged for him to travel on a Booker Transport ship to Georgetown.

He landed in what was to be his home for some time, one afternoon just as the sun was setting, and he had never seen a more glorious sunset. So when Mr Emsworth, a director of Booker Brothers who had come to meet him at his disembarkation and told him that he had secured a small villa on the bank of the Demerara overlooking the ocean, he was delighted. Mr Emsworth said that someone was looking after his luggage, which consisted largely of books, his photographic equipment and his microscopes, and would take everything to his residence, but that dinner was waiting for him at his own house near St George’s Church. Only when he discovered that Mr Emsworth and he did not share the same concept of the adjective small, did he express a slight reservation. How was he going to look after such a huge place? Mr Emsworth laughed; he would have to have people for that. People? Yes, servants. The concept of a single man having servants was completely inimical to Donald, although in Cambridge he had come across some insufferable toffs who specialised in speaking through their noses who had a valet in tow, who carried their books, dressed them, cleaned their shoes or their mess after they vomited after drunken bouts. He had thought that this was just a quaint aristocratic English practice. That would never do, he would not know how to deal with them. There was already a night watchman living on the premises, and he was part of the lease deal with the owner, an East Indian landowner, Emsworth explained.

Donald forgot everything when he was introduced to Emsworth’s daughter Charlotte. He thought that this time it was the true thing, a clear case of love at first sight. The haughty Hilve was but a pale shadow in comparison. Charlotte was like a dream come true. She was a bit on the tall side, reaching him to the ear when she wore high heels. She was a platinum blonde and had the loveliest nose he had ever seen on a woman. She had laughing, bewitching hazel eyes, and had obviously taken advantage of the sun, for she had a healthy and fetching tan.

Emsworth’s cook had prepared what was called a curry. Donald had never tasted that before, and was a bit disconcerted by its appearance. The observant Emsworth did not fail to notice his guest’s reticence, and assured him that once he tasted Shankar’s offering, he would become a fan for life. The daughter laughed a merry tinkling laugh which he found almost erotic. Although he had often fantasised about the opposite sex, he had never consciously entertained lascivious thoughts about them, but Charlotte aroused feelings in him that he wished he could keep under wraps — literally.

‘I assure you, Don,’ she said with a sweet little laugh, ‘my father is absolutely right.’ The mousy Mrs Emsworth to whom Donald had paid scant attention alarmed him by emitting a little squeak of a laugh, a distorted echo of her daughter’s, adding, ‘If you do not like it, which I promise you you won’t, I mean you won’t not like it… am I making sense Arnold?’ Arnold smiled indulgently at her, and assured her that she was.

‘If you don’t like it, I will get Shankar to make you a steak… the beef here is exceptionally good.’

‘No ma’am, I am sure I will like it. In my line of work, you see, I must expose myself to all sorts of new experience.’

‘Yes, Donald,’ Charlotte said enthusiastically, ‘tell us about the things you do and aim at doing here.’ But Donald who loved few things more than talking about science, was so overwhelmed by the young lady’s stunning presence that he became tongue-tied. He did not know that it was this momentary paralysis of his speech faculties which had helped him in his love quest.

In Toronto, Madeleine Rose Robertson was surprised when a big envelope was handed over to her, bearing stamps from British Guyana. First, there were three stamps with the queen’s head and one to make up for the full rate, was a magenta coloured 1 cent stamp with a signature. She did not expect the letter to be addressed to her as Donald usually wrote to his father with a few lines for her. To her amazement the envelope bore her name on it, in the boy’s bold handwriting. By the feel of it, she thought it was a lengthy one too. Perhaps he had enclosed a newspaper cutting; did they have newspapers there? She sat down on her rocking chair in the veranda overlooking her garden to savour it. There were at least four hand-written sheets, all in Donald’s bold careful script. She wiped off a tear as she remembered how she had taught him to write. She still thought that the letter might be addressed to his father, but she saw it right there: Dearest Mater!

Her hands were trembling and she made a mental effort not to cry, in the knowledge that her tears would make it difficult for her to read darling Donald’s words.

Taj Mahal Villa,

Georgetown,

12, January. 1863

Dearest Mater,

I hope you and father are both well, as indeed I am. You will be surprised at receiving this, seeing that I have usually only written short letters to you. Only now do I understand that I ought to have written to you more often in the past. And I will tell you why by and by. I remember father, in one of the rare moments of intimacy he and I have shared, telling me once that the first time he saw you, his immediate thought was, and I quote: “This is the woman I want to become the mother of my children!”

She stopped reading, took her glasses off and began wiping them, because the tears of joy gushing out of her as she took cognisance of these sentiments, had quite overwhelmed her. It was not often that she had received proof of love from the two persons she loved and cherished most on this earth. Yes, she had always supposed that Edward was fond of her, he was used to having her around, but she never knew about this. She read it again: “This is the woman I want to become the mother of my children!” . Why had he never told her that? But she loved him more than she loved God, and she had never told him that either; where would she have found the words? And Donald, whom she had suspected of not really caring for her, taking the trouble to write this long letter to her… dry up your tears gel, and read on.

The first time I saw Charlotte Emsworth, like father, I said to myself, ‘Here is the woman I want to be the mother of my children!’ Who is Charlotte Emsworth, you are wondering. I have decided to reveal all to you, darling mater. Mr Emsworth is the right hand man of Mr Connell at Booker Brothers, the largest English company in British Guyana, a company which he tells me was founded in the thirties. He kindly welcomed me to Georgetown when I arrived, as no doubt father has told you. He took me to his fabulous home on the night I landed and I ate curry for the first time. Curry is an Indian dish eaten with rice, and it is full of aromatic spices which are simply heavenly, although there is certain piquancy to it that I did not like at first, but found that it grew on one by the minute. I had not been three days here than I found myself addicted to the taste, and I daresay I could easily eat nothing else for the rest of my life.

I thought he loved my roast goose, she thought with a smile.

I promised myself to write a long detailed letter to you for once, and I am beginning to question myself if I am not boring you.

‘No, beloved child, you are not boring me! How can you say that!’ She heard herself almost shouting that out joyfully.

Anyway, the moment I perceived dear Charlotte, I thought no one can be as sweet and pleasant. She seemed bursting with intelligence and she has such bearing and presence. When I got talking to her, she confirmed my hypothesis that she was an accomplished young lady. She had stayed in Somerset, England, with her cousins who were being taught at home by their father, the Reverend John Emsworth, her uncle, and she told me that she loved few things in life above learning. She asked me intelligent questions about what I had studied at Cambridge and listened very attentively to my answers. Oh, on the first day we met, I could hardly open my mouth, so thunderstruck was I by her beauty. She was kind enough to say that talking to me had made her regret that there were no colleges for young women, that if it had been possible, she would have loved to study at a university too, but unfortunately there were none that girls could go to. I spend a lot of time with her, and Mr and Mrs Emsworth seem not to disapprove of our friendship. I will no doubt be in a position to narrate to you how this true to life love-story, not unlike one of Mr Reynold’s fictional pieces that I know, dearest mater, you are addicted to, like I now am to curries, develop. I pray that there will be a happy ending. Can I beg you to wish me the best of luck in my pursuit?

I know you must be keen to know more about the place, the people, the sort of things I do. British Guyana which is the old Demerara plus some other territories as well, and which I will subsequently call B.G. is about ten times bigger than Wales, and it is very varied in its physical features. Granny told us both, if you remember, that it is the only English speaking country in the whole of South America. I was told that Guyana means The Land Of Many Rivers in some Indian language. The Dutch and the French were here before us, but it is now part of our glorious empire. Georgetown is a quaint old city, built and designed by the Hollanders; we even have canals like in Amsterdam here. They built a series of sluice gates which are called kokers, where the canals meet the estuary. They form a barrier between the Atlantic Ocean and the canals, and at high tide they are opened to allow any excess water accumulated to be drained away. So, you see, we are safe. Oh, I forgot to tell you the most important thing, El Dorado is supposed to have been somewhere in this land.

My villa, which Mr Emsworth found for me was built by a rich East Indian gentleman who came here only twenty years ago as an indentured labourer, but who is now a wealthy land owner. It is built on stilts, and do not be alarmed when I tell you why. This town happens to have been built below sea level, and as a result, flooding is a real hazard. But the stilts are there to counter the effects of possible flooding.

Mr Emsworth said to me that there are few colonies which have more natural resources than B.G. Apart from the potential for all manners of cultivation, and I can mention sugar, balata (a kind of latex which is used to make rubber, for which there is going to be an incredible demand in the near future, he says), there are large deposits of bauxite from which aluminium is made. Keep this to yourself, but my informant also tells me that some geologists have indicated that there are reasons to believe that diamond is also to be found in some parts of the colony.

There are many new buildings going up in the town, sorry, city, as it has now acquired this status. I will not bore you with a long list of landmarks in the city, but the St George’s Church is one of the most impressive buildings you can hope to see anywhere in the world, it is made entirely of wood and is as far as I know, the tallest wooden edifice in the world. Incredibly there are railways operating quite efficiently here. The Demerara Railway Company operates passenger and freight services from Georgetown across sixty miles of track, down the Atlantic coast to Rossignol on the Berbic river.

The red and white striped lighthouse is an appealing sight, and I am trying to devise the means of taking a photograph of it to send you. As I will, indubitably, of all the striking buildings and monuments and landmarks.

I had the pleasure of accompanying Charlotte to a place on the river where there is the most spectacular and magical of flowers, a sort of lily which Mr Robert Schaumberg, a botanist whose works, which I read at Cambridge inspired me to come over here, named Victoria Regia, after our beloved sovereign. It has a diameter of the tallest man one can meet, and is of course circular. It looks like an enormous green plate floating on water, and at its centre is the most magnificent flower in the world, with a bright crimson centre surrounded by a pearly white ring and a rim of blushing pink. I shall paint a picture for you, for a photograph will not do justice to the colours.

As I said, I have a large house, and I rarely find use for more than one quarter of it. I have a whole room for my books! I shall convert it into a library later. I have secured the services of a cook, a young woman called Devi, who sleeps in a room in one wing of the house. She is very quiet and cooks delicious curries too, although possibly not as good as the Emsworth’s cook Shankar. There is a night watchman who doubles up as gardener; he came with the house, and is paid by Mr Ramnauth (the owner).

Let me assure you as I finish this long epistle, mater dearest, that I have never felt better in my life, my health is good, and I have met Dr Laker, a friend of the Emsworths who has kindly offered to advise me on medical matters, specially as I intend to travel in some unhealthy regions in the near future.

As soon as I feel settled, I propose to go on a long trip down the Demerara, as a sort of exploratory exercise which will dictate my future plans.

Give father all my love; of course without his generosity, it would not be possible for me to lead the extravagant and exciting adventure which I am already leading.

With all my love, dearest mater

Donald. R.

When she finished reading the letter, she was in tears. It was a private, intimate letter from her son to her, and she was not going to read it to anybody, she would only relate bits here and there to Edward. It was the happiest day of her life. It was funny how it could take a letter to do that; it was as if for the last twenty two years a mist had enveloped his filial love like her garden in a spring morning mist; you knew the spectacular irises were there, but before seeing them, you had to wait for the mist to lift; in the same manner, she could always feel that his love was there all the time, and had wished for a clearer vision of it; now that mist had cleared, no power on earth was going to make it descend on that love ever again. Although she was not sure about God, and even less sure about the power of prayers, she was going to pray hard for his success in both his love life and his professional life.

Bless that sweet Charlotte, I already think of her as my own!

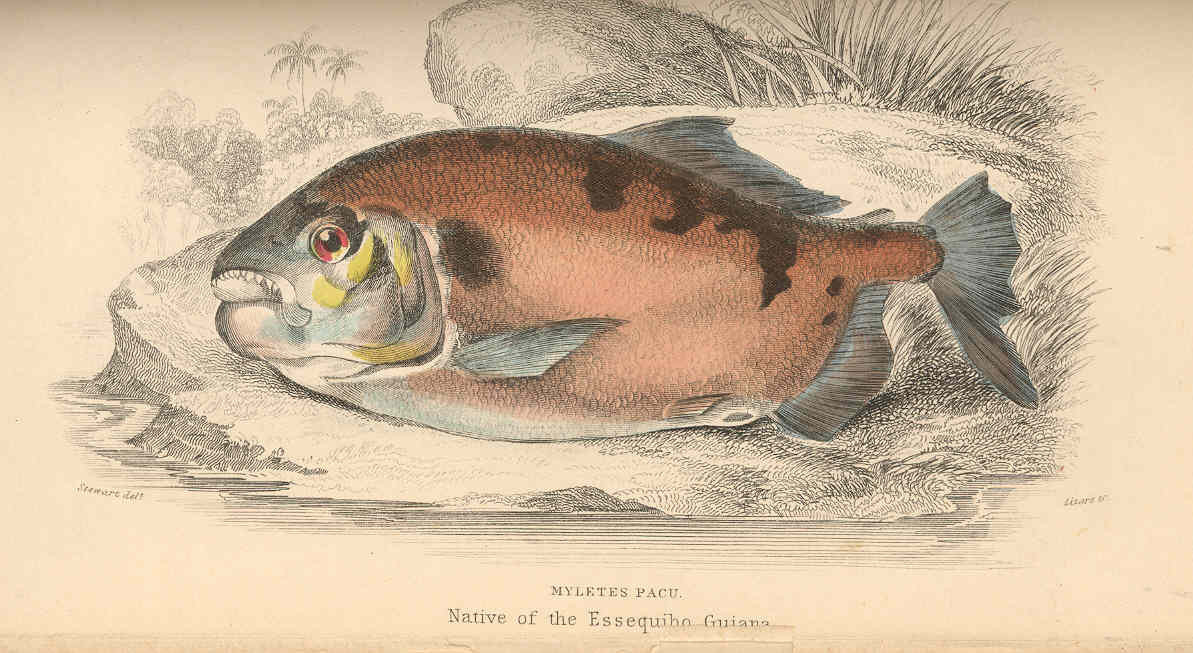

Photo Credit:

Schomburgk, R. H. (1852) Fishes of British Guyana,

Photo Credit:

Schomburgk, R. H. (1852) Fishes of British Guyana,

Donald hated the idea of leaving Charlotte in Georgetown whilst he went on a trip up the Demerara river. He hired a boat and a boatman, a squat Amerindian fellow who was all muscles called Yarreku, and made his first trip. Yarreku was a strange character; most of the time he had a frown on his forehead and appeared to be deep in thought, but on occasions, he was transformed into a fun loving, skittish fellow who could guffaw louder than Don’s fellow Cambridge undergraduates when they went on the King Street run.

The boat was of the type called candoa made and used by Carib Indians from light wood and bark of trees, and Yarreku, who spoke in words rather than full sentences said, Unsinkable, when he showed him the boat. As the currents at the mouth of the estuary were usually very strong, the boat was moored up the river a good mile away, so the pair of them walked, each carrying enough food for a short two-day trip, and some equipment, Donald in a rucksack on his back, and Yarreku in a thick wooden box which miraculously stayed finely balanced on his head, in spite of the uneven terrain and his propensity for scampering about at a pace.

The water was dark ochre and its flow was quite ferocious, which would have made Donald feel apprehensive, but he was too impatient to start his life of adventure to let fear come into the equation. Yarreku was endowed with incredible strength.

‘Sir Donal,’ he said, ‘you sit, Yarreku look after boat.’ He had tried on many occasions to inform the Carib man that he was not yet a knight of the realm (although he fully expected that at some point in the future he would be graced with that title, for his contribution to science), but the man seemed not to understand. He was ever to remain Sir Donal. The current was so strong that the boat began by going downstream, but Yarreku only smiled and after what did not seem to the young Canadian to be a powerful stroke, he managed not only to stop this, but to make the craft creep upstream. It was like magic, the budding scientist would write in his diary. After a while, the current seemed to become weaker, and the boatman invited him to try his hand. At Cambridge, he was not prepared to neglect his studies, so he had to content himself being a mere Sunday sculler. As they went up river, the vegetation became denser and more luxuriant. He made the boatman stop now and then, hopped on the bank, set up his camera and took photographs of plants that looked unfamiliar. Flora was an area that was of limited interest to him, but he had read Schaumberg’s papers and knew his Linnaeus, and he meant to show his pictures to some expert botanist friends. Yarreku was perplexed by the camera, and when Don explained to him what it did, he was not sure whether he had made any sense to the man. They stopped on the island of Borselm, which used to be the capital of Demerara in the days of the Dutch, but it was now almost deserted with most of the built-up structures in ruins. As they were sitting near the water, eating, Yarreku said, ‘Look, Sir Donal,’ pointing to the water, where there was a hardly perceptible ripple. A caiman, he thought, for that was something he wanted to see. No, his guide told him… anaconda. Then he saw it, a yellow anaconda, swimming towards them. As the water was clear, he could see the dark bluish patterns on its body. Yarreku was not watching the snake, but looking intently at the young scientist. Don guessed that the snake was about twenty feet long. Suddenly the serpent changed course, and they watched it disappear. The Amerindian smiled, spat in the water and dismissively said, ‘Him small!’. What did he mean? He explained by pointing to his eyes, which meant that he once saw one specimen, then by tracing an invisible line between two palm trees which must have been a hundred feet apart, suggested what he thought the length of the reptile was. Later he would discover that Yarreku was not given to exaggeration. They spent the night on the island. He would not have been able to photograph the anaconda, so he sat down on the grass and made a sketch of what he had seen. If he saw nothing else of interest during the trip, this sight alone would have made it worth while.

On the island there were a large number of birds, many of which he had not even seen pictures of. Where possible, he took photographs. But the great find of the trip happened on the island as they were preparing to leave in the morning. Yarreku suddenly grabbed Don’s hand in an obvious signal for him to stop. Then gingerly he inched forward, controlling the white man’s movement at the same time, his free hand on his lips to demand silence. Don followed him closely, and the Amerindian bent down noiselessly and pointed to a hole in the ground. At first he thought it was a rock, but then he saw it, a grey ground-dove, resting in its nest in the ground. He was about the length of his outstretched palm, from the tip of his middle finger to the rim of his wrist. It was ash-grey, and its wings had dark violet but shiny markings. Don began to assemble his tripod, and to his surprise his companion who until a day ago, had no idea what a camera was, instinctively seemed to know how to help. He was able to see the object of his fascination through the lens. He took a deep and silent breath and pressed the shutter. Only then did the bird become aware of alien presence and took to flight.

‘Lucky the dove did not fly away.’

‘No luck, Sir Donal, Me make bird still.’ Was he suggesting that he had some strange gifts?

‘Yarreku, you saying you have gifts?’ The man nodded.

‘Then why did you not get that anaconda to wait?’

‘Make him come forward, no can make him stop in water.’ Maybe he was a joker.

The trip lasted no more than two days. Back in Taj Mahal, he had a wash, and had just finished putting on his suit when Devi knocked on the door. She seemed truly pleased to see him, and Don could see her hesitate before asking if he was staying at the villa for his supper. No, he said, he was going to see some friends. He noticed the look of delight transforming into one of disappointment. She bowed slightly and left. He went to the Emsworths, as he had promised Charlotte. They sat under the open verandah, and he gave her a detailed account of his first trip. She was very keen to hear everything, and asked many questions. She laughed when he spoke of the prowess of Yarreku.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Zweer de Bruin

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Zweer de Bruin

‘Yarreku? Was that his name?’

‘Aye, why?’

‘Yarreku means the monkey in Carib language.’ Don thought that it was funny that a man would not mind being called Monkey.

He was greatly heartened to find that she was indeed his soul mate. Perhaps some day, when he felt more confident, he might invite her to join him on a trip. Not only would that be a wonderful experience which they would recount to their grandchildren some day, but she might well be of help, as she seemed to have a great thirst for learning. He caught her staring at him, and asked what the matter was. She hesitated before answering.

‘Father is out, and Mum is busy in the study,’ Don nodded, enquiring with his eyes if that meant anything. She nodded first.

‘If you want to kiss me, I am sure it’s all right.’ Don had been dreaming of doing just that for days, but now he seemed shocked that she should volunteer. Yes, of course, he said, walking towards her. She stayed seated, and he bent down clumsily, put his hands behind his back and approached his lips to hers. She stood up.

‘Not like that,’ she said, grabbing his arms and putting them firmly round her waist. He needed no more instruction. He smiled, tightened his grip, pulled her towards him, making a sly effort to involve her pulsating breasts in the process, and that moment when the two pairs of lips met, is something which he promised he would never ever forget. She responded with equal passion, rubbing her breasts against his, and they stayed like that, holding each other and kissing, at first lips against lips, gently stroking them, and when nature dictated, they began searching each other’s tongues. A fellow undergraduate had explained to him that that was the ultimate aim of kissing, that it was called a French kiss. He had also explained that a kiss was a prelude to sexual intercourse. And indeed, he felt deeply aroused, but he knew that he should not contemplate that sort of thing before they were wed. On second thoughts, not before they were officially engaged — or at least when he knew that they were going to be engaged. There was one more step, and he took it: when we get to know each other better. But even then it was going to be very difficult.

‘I know what you boys are like,’ she said, rubbing against his hardness, ‘but my answer is no.’ Don looked at her guiltily, as if he had propositioned her. ‘Not tonight anyway,’ she said. He was pleasantly surprised by this, but the look on his face had, as yet, only registered the surprise and not the magnitude of the promise.

‘Don’t look so disappointed, I will arrange it very soon… when they go to play Bridge with Doctor Laker. The servants will keep their mouths shut.’

On his way back home in the Emsworth’s ghari, he could not stop whistling. He got out and almost danced his way up the steps of his new home.

Devi immediately appeared and asked if he wanted a nightcap, and he declined. He was so happy and lightheaded, he thought he had to be extra nice. The hardness was still there, and he felt a little wetness in his underwear.

‘Don’t run away, Devi, you aren’t in a hurry?’

‘No, master.’ He indicated with his head that she should come into the veranda and asked her to sit down, pointing to a chair, but she let him sit down first, and then squatted opposite him, on the floor. He pointed to the chair again, but she shook her head violently.

‘Tell me Devi, are you alright?’ She looked behind her in astonishment, as if she would find the answer to that unusual question there. She nodded violently.

‘I mean, are you happy here? Enough money? Not too much work?’ She shook her head in that special manner Don had noticed East Indians did when they meant to say no. Then remembering that he had asked two questions, she started nodding, a yes to the first question. Don thought that a shy young woman saying yes and no simultaneously was a comical sight, and laughed, and she smiled tentatively, unsure about what had caused the hilarity.

‘Tell me,’ he said, ‘what made you come to work for me?’ She frowned. Why did people work for other people if not to get money so they could live, she was thinking. Why is he asking. Perhaps they were all the same, he must be after something. She raised her eyes furtively in an attempt at assessing the man. He was well-built and handsome, had a kind face, but that was not enough to make him a nice man. He was obviously well-fed, and his frank open face told her that he had never been bullied by anybody, that the whole world loved him. He had never known what it is like to feel cold or go to bed hungry. But I suppose, she told herself, that all his advantages did not stop him suffering the same as us when he has toothache. She had not realised that she had smiled as that perverse thought crossed her mind, and only became aware of it as she noticed him smiling in return, clearly not because he could read her mind, but because, she supposed, hoped, that he was probably a good-natured man after all. But that badmash, that rogue, Jeewan, had already taken her virginity, she had nothing to lose.

‘My father, sir, he not working, I must earn so we eat.’

‘Oh, I see,’ he said. No, she thought, you don’t see, how can anybody?

‘My father sir, he lose mind. People at the Mandir they look after him, but I must to pay for food.’

The Pandit had said that he could stay under the banyan tree in the compound for free. He had even provided him with a piece of sailcloth for shelter in case of rain, but Baba needed to eat too. The people would give him food, but she did not want them to think of him as a beggar, so she had to find some money. Her hope was that one day she might be able to make enough money to rent a small hut where they might live together. Especially as now, after what happened with Jeewan, nobody would want to marry her, she thought. She did not plan to tell the white man all this.

‘He has lost his mind? Do you mean he is…’ he was unable to say the word.

‘Yes sir, he mad, not know where he is, thinking he back in Calcutta…’

‘I am so sorry to hear that, what happened?’ No, she was not going to tell him, she shook her head, and he saw how tears had filled her eyes, and he decided to drop the matter. She stood up, and asked if that was all, and he nodded.

‘Can I bring pipe, sir?’ What an excellent idea, he thought and nodded.

When she brought his pipe to him, he smiled at her and said thank you, thank you, Devi, and as she was going back inside the house, he stopped her.

‘Oh, Devi, I meant to tell you, you cook beautifully, your prawn curry last week was an absolute masterpiece.’

‘Master what?’ He explained and she seemed so happy. What an excellent day, what an excellent everything!

Devi was both relieved and disappointed. Relieved to find that the man she had admired almost from the beginning had not behaved like a cad, and also a bit disappointed, because she would have liked what she feared he was going to demand of her.

A week later, Jonathan, the young freed slave who worked for the Emsworths came with a note: Tonight is Bridge Night. There was no signature, but a tantalising print of lips as made by a very special crimson lipstick that Charlotte favoured.

He got a cariole to take him across the city to her place, his heart thumping with anticipation. He was certain that he was going to make a mess of it, but found comfort by telling himself that everybody did, the first time. He was surprised when the first thing she did was to give him a French letter, probably made of sheep intestine. He had seen one before in Cambridge when his friend Lord Blankhead produced one at a party and regaled the guests with his tales of sexual conquests. Charlotte told him that it was her cousin Clara who sent them to her, smuggled in one of the books that she regularly sent her by the post. She took him by the hand and led him into her bedroom.

He found that she was a good teacher, as obviously the mysteries of sex were not a mystery to her. She must have learned more than what her uncle had taught her in Somerset, he surmised wryly. He was too excited to give that much thought, and with her help, managed to give a good account of himself, although he was a bit shocked by her unguarded manifestations of ecstasy as she reached her climax. She lit a cigarette with a newfangled silver lamp, and they smoked it alternately. He did not really like cigarettes, he was not even sure if he liked the pipe, although he smoked one. She inhaled deeply, and pulling his mouth towards him, opened it with her tongue and blew the smoke in his mouth. It nearly choked him, and she laughed when he explained that he was not used to inhaling. It had been a memorable experience, even if it had shattered a few illusions about her. His friends at university had told him stories of their sexual encounters with so-called well-born girls, but he had not believed them entirely. Now he knew that there was so much about the real world that he had not the faintest idea about. He was pleased to find that he had not been put off by her colourful past, but he was certainly not going to confide in mother this time.

For a whole week, he never even went out of the house, so busy was he writing his notes about the river trip, making diagrams and sketches. On Saturday he went to dinner at the Emsworths’. But before they sat at table, Charlotte said she and Donald were going out for a stroll. Arnold did not even hear, but Mrs Emsworth said, We will eat in an hour and a half.

‘Then that gives us enough time,’ she whispered to Don with a smile.

‘Time for what?’ he asked.

‘You’ll see,’ she said and he followed her meekly.

The house of the Emsworths was on very spacious grounds, and in five minutes, with the luxuriant growths around, they seemed to be on a desert island. A macaw flew overhead. Don followed Charlotte to a cosy clearing where there was a man-made grass mattress with a cotton sheet on it.

‘I thought that this would make a nice little love nest,’ she said, ‘I made it for us myself.’ Don knew that he ought to show some disapproval, but he was too overwhelmed by the prospect of what was in wait. She fell on the bed of straw and dragged him down. The world stood still.

When he went back to the villa, Devi was still up and waiting under the veranda, in case he wanted anything.

‘Devi, you should not wait for me, you need your sleep, you’ve been up since before the cock crowed.’

‘No, all right.’

‘I don’t really want anything, you go to bed. I am sorry I deprived you of your sleep.’

‘No sleepful,’ she said, beginning to get up.

‘Sleepy,’ he corrected automatically, adding, ‘if you want, you can keep me company, and tell me about your father.’ She shook her head in a determined manner.

‘Of course, not if you don’t want to, sorry for being…’, he could not find the words, and added, ‘how about if I tell you about Miss Charlotte?’ She nodded enthusiastically. ‘I am in love with her, Devi.’ She smiled happily and bent her head.

‘I am going to marry her.’ She raised her head and smiled again. She obviously wanted him to be happy.

‘Wouldn’t you want to be married, Devi?’ She did not answer, but shook her head violently.

‘Why not? You’re a sensible young woman, beautiful, you’ll make someone a good wife.’ She stood up.

‘Now, I sleepful. Good night Master.’

A few days later, Donald who had been working all day was drinking a small whisky and smoking his pipe when Devi appeared, to ask if he wanted anything.

‘I would really like to know why you were upset when I asked you if you wanted to marry some day.’

‘An impure woman can’t marry sir.’

‘What do you mean, Devi? You are not impure.’ He had heard about untouchability, and thought that it was a great shame.

‘No man will marry me, because I am…’

‘You are what? Is it a caste thing?’

‘No sir. I impure.’ Why is he pretending he does not understand, she thought.

‘A man wants bride pure on first night, sir.’ Finally he understood. What a silly notion these people have! Does that mean that I should not marry my Charlotte? She certainly is not pure. But somehow he could not believe that Devi would have had the same history as the white girl, who clearly had been all for it.

‘Did you have a lover then?’

‘No, sir,’ she said, tears dripping down her cheeks, ‘he took me by force.’ Don stood up angrily, very upset, and started pacing up and down the veranda in an extremely agitated fashion.

‘Who did? Who’s the cad?’ His anger was such that if he met the man who did this to her, he, who was not given to physical violence, felt that he could have throttled the villain.

‘I can’t say, sir, please don’t ask me. Can I go bed now, sir?’ He was too moved to say anything, he just nodded, and she left quietly.