The Coimbra was going to stop at Nossi Bé on the big island of Madagascar for water and provisions. Midala had been surprised at the ease with which information could be transmitted now. The crew often talked among themselves in the hearing of the captives, in the belief that no one understood them, but there was always someone who did, and as drum telegraphy had become widespread, a few taps, and everybody was kept informed.

The warrior often wondered whether what had been happening over the last weeks was real. Perhaps, he thought, I died when we were attacked, and I have gone to the Bad Place, and I am paying for my sins, but he had not been a bad person, never knowingly done anyone any harm. As a soldier it was his duty to fight wars but he never killed wantonly. He had always been there for anybody who needed help, been kind to everybody. He loved his wife and children, never stole or told lies. He had never betrayed anybody in his life. Maybe he was not good enough to go to the Good Place right away, but the Spirits are never unjust, and he felt sure that he had not done so many wrong things that he should be punished to that extent. But he was undaunted, and in spite of being kept in chains and under almost constant surveillance, he had not given up hope of a decisive action.

Having been apprised of the stopover, he thought of the possibility of a massive breakout, in the hope that they would find the island hospitable. But the problems were many. The chains had to be removed before anything could be done. After the death of Bomo, he had not found a reliable man to discuss his plans with. He was pleased when Bomo had explained the intricacies of the drum language to him, how to produce two high, two low and a middle note by tapping on different thicknesses with different materials. He had realised the importance of this, and had not only perfected his technique, but also taught a number of people in his hold, and had urged those in the other holds, where there was invariably one or two initiated in the art, to do the same. They were all amazed at the ease with which they were able to communicate with each other. It was thus that he had learnt of the fate of Matamba, a young mother with a toddler. She was a stunningly beautiful woman, and it was not long before she had attracted the attention of the crew. A second mate promised to see that her sick and ill-fed baby was fed properly in return for sexual favours. She had lost her husband when the village was sacked, and the first time she had cried out in horror at such a suggestion, but it was explained to her that if she did not consent, she would be gang-raped anyway, and the baby would suffer. She had no choice but to submit to the demands of the man. The baby died all the same and was thrown overboard. She was then passed around from man to man, including the captain, and had learnt to accept her fate. She had always shared whatever tidbits her ravishers gave her, as a sort of reward with her wretched companions.

Midala knew that sending out messages by tapping them out was fraught with danger. Their first plan was wrecked because it had been betrayed. How could he be sure that future plans would not meet with the same fate? He had, however, felt that greater solidarity had developed between the prisoners after the death of the poor sick woman and the suicide of Bolimbo. Everybody had witnessed how a poor man had been driven to betray his own people in a futile attempt to save his wife, and no one was likely to forget it. So he decided to take the risk, but asked everybody to be vigilant, and watch for possible traitors trying to pass information to the crew. The crew totally ignored the tap tapping going on, and dismissed it: those savages, all they think about is music and dancing, they would say. It was true that one thing that allayed their wretchedness was singing and making music with whatever was available.

Midala had enlisted the help of Pumpino from Hold 2. The two had never met, but had conversed by drum telegraphy. The younger man had impressed him with his quick wit and daring words, but his actions were yet to be tested. Thus he became a natural second-in-command. They communicated several times daily, and they managed to identify and enlist four young men and two young women who seemed to have all the right qualities to carry out a lightning action on the captain and his crew. But they were only going to go ahead with this desperate plan if their fellow victims agreed that it was worth risking their lives.

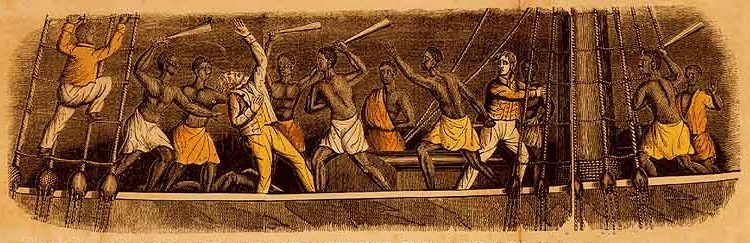

He sent out a message suggesting that they should attempt a massive breakout when the ship reached the port, explaining that there was every chance that a large number of them would be shot dead. He was surprised by the reaction. Messages flooded in, all with the clear indication that whatever the outcome, doing nothing was cowardly. They had had a taste of slavery, they claimed, and if death resulted in their attempts to regain their liberty, they were willing to take the risk. He was greatly heartened. He asked if anybody could provide them with implements like files and iron bars, so they could file away their chains, and then fight their captors. That was when Matamba promised she would do all she could to help. Left alone for even the shortest of intervals in the cabin of whoever was taking advantage of her, she rummaged around and in less that a week, she had been able to lay hands on four files, a number of nails, a butcher’s knife, an axe and two spare axe handles. Midala arranged for these to be collected at pre-arranged caches by people in the other holds, so they could be picked when required, and everybody set to work to free themselves and prepare for the big breakout. He had repeatedly stressed upon the merit of a concerted action, and had explained that only if people did exactly as they were told, would there be any realistic chance of success. If anybody did anything unplanned, they would bear the serious responsibility of the mission’s failure. At a given signal from him, they would all rush out of the holds in an orderly fashion. The strong swimmers among them would then jump into the sea and swim to freedom, and the non-swimmers would gather near the lifeboats whilst Midala and Pumpino, and half a dozen young stalwarts would disarm the captain and the first mate, hold a knife to their throats, thus paralysing the rest of the crew, after which they would launch the lifeboats. They would then land on the big island, and go in hiding from both the crew of the Coimbra and the natives of the island, having no idea whether they would be hostile or not.

On the morning the ship sailed into the port of Nossi Bé, Midala, having got rid of his chains, slowly crept out of his hold. He did not expect any signs of the break out just yet. He paused as the incredible beauty of the cerulean seas and the golden sands hit him. His companions held their breaths in expectation, but suddenly a loud splash was heard. Some captives from Hold 3, in their impatience had rushed out and jumped into the sea, fatally compromising the action planned. The captain and his men surged forth brandishing guns, shooting in the air to create panic whilst making for the railing, from which they started shooting at the fugitives. Midala did not want a bloodbath on deck, and was once more frustrated in his attempt to lead his people to freedom. Clearly the Spirits did not wish it! Six of the fugitives were hit, and drowned, but three of them were unaccounted for. Did they make it to the shore? Were they able to enlist the support of the islanders? Midala would never know, but felt sure that they were much happier for having dared, even if their indiscipline was criminal.

Life on board returned to normal, and surprisingly the captain and crew, who were drunk most of the time, mystified by the severed chains, decided that it would be too complicated to do anything about it, seeing that in a couple of weeks, the troublesome captives would stop being their responsibility. All he did was to order his crew to stop “mollycoddling our guests.”

After Nossi Bé, the Coimbra met with favourable winds, and reached the port of Mahébourg on the south-east coast of the Île de France in under a fortnight, and without any incident, if one discounts the death from cholera of a handful of captives in Hold 2. They were unceremoniously despatched to the deeps, as usual, together with one old woman who had not quite died, Flyte-Camilton having decided that it would save time on the morrow, when she surely would have.

On the final day of their journey, the captives were allowed to wash, and the sick were attended to. Those captives with visible scars and wounds were treated with a variety of products, including a mixture of mud and coal tar, applied to crevasses in their bodies in an attempt to disguise the damage done to the product, so as not to incur the wrath of their lawful owners, who had paid handsomely for it. Most of them were naked, even the women, but by now they had ceased to care about minor considerations like modesty or pride. All the scrubbing and mending could not disguise the fact that they were a sorry sight and had gone through hell. When they came down the ladders, without their chains for the first time in months, Midala thought that even if they kept him in chains for the rest of his life, he would never give up hope of liberty. However it was now known to everybody that they had been sold to plantation owners who needed them in order to cultivate their land, so there would be no logic in keeping them in chains. His course of action was clear to him, he would keep his head down and plan his escape as soon as the occasion arose. The Spirits knew that he had been a true son of the tribe, and had tried his best to bring succour to his folk, but in their wisdom they had withheld from him the means to do it right. He had tried and failed, so now he was not going to try for them anymore. Six people had died because of him, and now he was not going to do anything to risk the lives of others. He would find the means for his own salvation, and he was going to act cautiously and slowly. The sea was calm and clear, and everywhere around there was luscious green vegetation. Ahead loomed a large hill which looked like a lion at rest. In spite of his disenchantment at his condition, he had a good feeling about this place which reminded him of his native Inhambane.

He was herded in the company of the men and women who had been branded together. They were under the watchful guard of a handful of armed guards, all black men like themselves, armed with guns. It pained him that people who in all likelihood had suffered the same tribulations from the slave-traders would show so much hostility to them. No sooner were they in a large shed on land than an irate white man — he was more red than white — burst in upon them and started haranguing them in an unknown language, becoming redder by the minute, as he spat out his spiteful words. He was a stocky man with a head that was almost square, his grey eyes that were too close to each other, with thick set features, wide shoulders and disconcertingly short dumpy legs. Nobody understood a word he said. After a while he beckoned a slender and tall grey-bearded black man, and when he approached the master, Midala noticed that he walked with a limp. His beard was sparse and uneven, his eyes bloodshot. The red man spoke to him in kindly tones, and then turned round looking for Flyte-Camilton. The lame man then began to address them in Chopi language. He said that his name was Antoine Gentil. You too will be given a new name, he said in a mild and gentle voice, and you will do well to forget the name you were given at birth, because if you are heard using it, the punishment would be a substantial decrease in food rations. Midala kept his emotion under control.

The limping man said that he was glad they had survived the boat trip, he knew how tough it must have been. He explained that the irate man was their owner who had placed an order with Captain Flyte-Camilton, through an agent in Zanzibar, for a certain number of able-bodied slaves. First, one third of the slaves he had paid for were missing, and he was angry because you, the survivors all seem on the point of death. He smiled apologetically and explained that he was only translating the words of Missié de Fleury. Do not worry, he told them, your wounds will heal and you will regain your health much quicker than you think. If you do as you are told and do not rock the boat, you will be fed, given medicine and kept under a roof. What more does a slave want to survive? This white man is a tough one, so you had better start on the right footing with him, because he takes nonsense from nobody. Everybody knows the reputation of Missié Victor. Take my advice, do not under any circumstances cross him, for you will regret it. When an army has no weapons, the best course is to sue for peace. It really would be a complete waste of time to attempt to escape. Many have tried and no one has succeeded. This is a small island, and the Anti-Maroon Units are known for their vigilance and their zeal. They know all the hiding places and last time someone tried to run away, he was caught on the same day before the sun had set. The poor fellow was dragged back to the plantations, tied to a mango tree and the white man himself whipped him and finished him off. It was the law of the land. The runaway deserves no less, Gentil said, and it is in your best interest to remember this at all times. Think of Missié Victor as your father, your mother and your god. He has all the power, and if he decides to beat you to death, it is his right, there is no one to prevent him.

Antoine paused for a short while, looked left and then right to make sure that no one was eavesdropping, and proceeded in a whisper. No, he confided, it is not the law of the land actually. There is something called the Code Noir which makes it illegal for the slave owners to dish out justice themselves, but the plantation owners did as they pleased because they all drank and partied with the governor and the top administrators. There is nobody to stop them. In fact, according to the Code Noir, escaped slaves should be sent to the Bagne there, and he pointed in the direction of a building which they could not see properly. The conditions in the Bagne are much worse than any plantation owner can dish out, trust him. You work from dawn to sunset, carrying and breaking stones for construction work, you got fed the same thing day in day out, manioc and pumpkin, dal and spinach, and you are kept in chains all day long and often all night long too. You sleep like animals, twenty to a room, because there are too few guards. The hand-picked guards are sadists and are very eager to use whips, sticks and their own fists as well. But if like me you abide by the law, as it is practised, do your work with a smile on your face, you will have a decent life, you will get food which you can cook yourselves and decent clothing. If not, I pity you. Welcome to Île de France, Vive le roi!

Missié de Fleury reappeared, and as the captain had reimbursed him some of his losses, his redness had given way to pink. He made another speech, but this time did not ask Antoine to translate, not minding that no one understood. The tone of his speech was one of heightened anger, and this was all he meant to convey to the men.

The slaves were tied together securely, with a brown man with a straw hat, brandishing a whip in charge. He was followed by some black men in khaki, armed with iron rods and machetes, and they were ordered to march in silence. It was mid-morning when they started, and, with whips much in evidence, were made to walk at a brisk rate. They walked through the bush where the trees looked very different from those of Inhambane, except for the few ebony trees and aloe plants which grew here and there. Midala found that link comforting for some strange reason. They crossed some rivulets, and often the path led towards the beaches, and he thought that they looked much prettier than back home. It was much after dark when they reached their destination, when they were taken to a large room with corrugated iron walls and a straw roof. He was grateful for the yam, boiled pumpkin and pili pili sauce that they were given, specially as the sauce was how they made it in Inhambane. Some candles were lit and placed on the floor, for there was no furniture in the shed. There were some rolled gunny bags in one corner, and they were told to pick two per person, and use them as a bed to lie upon and a blanket. The men were to occupy one end of the hall, and the women the opposite. And we do not want any funny business, the guards warned them, you are here to work and not to indulge in fornication. Midala was surprised that the men spoke to them in their own tongue, but to each other they spoke a language which seemed similar to the one the red man had used. Later they would discover that the red man spoke French and the guards spoke kreol which seemed similar. They were warned that the door of the hall would be locked and that sentries would be on patrol outside with dogs which were only fed in the morning, in case anybody got some funny notions.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-ND llee_wu

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-ND llee_wu

At dawn next morning, he was greatly comforted by the chirping of birds, and through the chinks in the walls, he could see birds he had never seen before and did not know the names of. He would learn later that they were red cardinals which were unique to the island, green parakeets, which Midala would later learn were called catteau vert, flying from tree to tree, golden yellow canaries and many others. There were tamarind trees that he had not seen before, flame trees with their distinct flaming red hues, bois noir, mangoes, avocados, papayas, and several others that he could not identify, either because he did not know them or could not have a proper view of them. In the uncleared bush, growing wild, he would discover the most succulent and the tastiest little round fruit that he had ever tasted, and he would learn that it was called goyave. The guards came and unlocked the doors, and they were let out, for the first time, unfettered, but the presence of a large number of well-armed guards was more than enough to deter any thought of escape. As he emerged from the shed, he was greeted by a sight which cheered him up considerably. They were under a mountain which immediately reminded him of the breasts of a woman even if they were pointing upwards, and there were three of them. He would find out later that it was called Montagne des Trois Mamelles. In the morning hue, the mammaries appeared blue with white light reflected on a face which seemed as if they had been fashioned by human hands. Lucky devil, thought the warrior wryly. The mountain was nothing as big as those back home. All the features that he will see, will strike him as being miniatures, but he thought this was what made them beautiful. As a child, he had thought that the dwarf rooster an aunt gave him was the most beautiful bird that the Spirits had created. In spite of his small size, he was fearless and even the massive cockerels kept out of his path, and the hens simply adored him. He could hear the soft tingling of a rivulet flowing, and indeed it was a small river — everything was on a reduced scale on this small island — and its water was crystalline. He did not think that having been forcibly taken to another country he would find anything good in it, but in spite of himself, he found that he was liking his surroundings. Not that this made the slightest difference to his refusal to accept enslavement.

He had promised himself that whatever the consequences, he was going to run away at some point. Flogged to death? What is death? No man is immortal, although the soul was, and no power on earth can imprison the soul. But he was not going to run away just yet. He would keep his head down. All his previous attempts had failed, no doubt because they were carried out in desperation. His plans must have been defective and could never be reasonably expected to succeed, but the next one will be his final one. Since they had to work, they would not be in chains, or yoked in any way, and the land provided more scope than the sea. He would either make it or die! He would keep is eyes and ears open, find as much as he could about the lie of the land, ask discreet questions, and put his fate in the hands of the Spirits.

Missié Victor’s appearance, with Antoine following, put an end to his musings. The red man went to speak with the guards, and the limping man approached him. He was the white man’s slave, and had to do his master’s bidding, but Midala did not have any bad feelings towards him. He began to ask a few questions to which the warrior replied curtly. The old man then looked away and in a stammer informed him that Missié Victor was going to be give them their names.

‘What do you mean? We already have names,’ he said, and Antoine laughed defensively.

‘No,’ he said, ‘not savage names, new names, civilised, Christian names.’ Then, making sure no one was listening, he whispered, ‘Antoine is not my real name, I am from the royal family and my true name is Colibango.’ And he smiled proudly at this, showing his near toothless gums.

‘My name is Midala, and I don’t want a new name.’ Antoine tut tutted sadly. ‘No, you must, just take the name, say nothing… or better say merci missié.’

‘Missi Missé? Why?’

‘It means thank you in the language of the country.’ Midala shrugged, ‘my advice is don’t draw attention to yourself… then you will be all right. You will have two meals a day, nothing fancy, but the hyena eats the dead, and in times of need even the lion will eat grass, remember.’ Midala said nothing, and Antoine went to speak to some of the others. Suddenly he turned round and said, ‘Not missi missé… it’s merci missié.’ Midala nodded almost imperceptibly. Antoine looked at him thoughtfully, not moving, and finally said, ‘And please my brother, keep your head down.’ Brother, Midala mused.

Later Victor de Fleury summoned them in his presence. One of his men had a ledger, and a small coffee-coloured kid carrying a small ink pot. The master, now pink, seemed less irate than earlier on, and made a speech which Antoine translated. It was what he had told them earlier on. There were a handful of brown men who were neither white nor black, and two or three black guards in his proximity, no doubt slaves who had behaved and were given some position of trust, and they were talking to each other in Chopi. The captives were required to line themselves up, and to move forward at a sign from one of the minions. The first one to be given a name was a frail grey haired old man. Midala wondered how he had survived the horrors of the voyage.

‘Look at you,’ de Fleury said laughing, ‘you look like you’re already dead.’ The guards and minions laughed exaggeratedly.

‘You name shall be Mourant, Jean Mourant.’

The guards burst out laughing, explaining that Mourant means dying. The scribe wrote the names in his ledger as the names were dished out.

The naming ceremony went on at a pace. The various names Midala heard were, Marie Vache, Michel Bouteille, Henri Marteau, Denise Vilain, Marcel Mardi, Jules Crétin, Jeanne Grocul. When he learnt the language of the island, he would gather that these were risible names, meaning Cow, Bottle, Hammer… When it was his turn, he took two steps towards the white man, remembering Antoine’s injunction not to make waves.

‘Look at the sour face of that fellow,’ de Fleury said to the guards who laughed out aloud, ‘doesn’t he make you think that he has eaten some hen shit?’

The minions shook with hilarity, nodding their agreement with what the wise white man had just said.

‘Your name shall be Louis Cacapou.’

‘Merci Missié,’ he said. And Antoine breathed again. He will find out later that Cacapou is a shortened form of Hen Shit.

Thus he started working for Missié Victor. It turned out that he had sugar plantations all over the island, and was in the process of building a factory for crushing cane and turning it into raw sugar. He had recently bought fifty arpents of rugged land near Sept Cascades in the region called Tamarin, and he wanted it cleared and the new arrivals, of whom a little less than half were women, were all marched there.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Herr Olsen

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Herr Olsen

On the first day, they were required to build a shed. This work was supervised by a pale and callow youth in shiny leather boots reaching up to his knees and wearing a pith helmet. He shouted a lot but was not otherwise violent, his main preoccupation seemed to be keeping his boots clean. The armed guards of whom some were black, others white or mixed, were not as fierce looking as those on the Coimbra. They surprised themselves at the speed with which they were working. Midala marvelled at the capacity of human beings to pick up the pieces and get on with their lives. When the sun was right in the middle of the sky, they were allowed to stop and were given the means of cooking their own meal. The company had provided manioc, spinach and pulses. The women set to work whilst the men were allowed to smoke pipes which the guards produced for them. The women teased the men for being lazy bones, and this was the first time since the night of the attack that Midala had heard the sound of laughter. It took two days for the work on the shed to be completed. People allocated themselves areas of the floor without any major arguments. On the next day, they were be led to the fields, when serious and more back-breaking work was expected of them.

The callow youth was replaced by an unsmiling white man who was rather older and he shared out the work. Instead looking after the shine of his boots, he constantly followed a small party and never stopped berating them for one thing or another. He hit a man in the face with his whip because he thought he had looked at him with disrespect. He looked at Midala pointedly, but the latter kept his head down and continued digging.

Forgetting his resolution not to involve others in his plans, he thought that this time, they had pickaxes, machetes and spades, numerical superiority, and that it would be easy to overpower the supervisors, or colons, as he soon learned they were called, but where would they hide afterwards? How would they feed themselves? He might discuss this with his fellow slaves at night, but there was a danger that he might yet again be bounced into a half-baked scheme. He thought that the best course was getting to know his companions better.

The clearing work proceeded at a good rate, although the colon continually expressed his dissatisfaction. Every day he found a pretext to whip someone. He kept picking on the three men and a woman who were erecting a wall with the rocks that had been removed from the soil, saying that it was too high or too low, or maybe both, and when the leader did not immediately acquiesce, he grabbed him by the scruff of the neck and dragged him towards a bois noir. The guards ran to his assistance, and were asked to tie the fellow to the tree. He then began screaming at him, and ordered a guard to give the man twenty of the best. This, the man did this without too much relish, but when he had finished with him, left the victim more dead than alive. The colon then came to him and offered him a swill from a bottle of rum, which the man first refused, but he immediately changed his mind, in case he was given another twenty for insubordination.

The whipping and flogging was a daily routine now, but Midala had so far been spared. At night they would sing sad dirges about their lost homeland and dear dead ones, finding new words to describe their pains. The women, who were in better shape than the men, because the rape that they had endured on board, as opposed to beatings, had left them more mentally than physically damaged, began to tend the poor male slaves, and in no time couples began to be formed. Midala wanted nothing to do with women, he was still in mourning. Matamba, the most desirable woman on the Coimbra who had had to submit to crew and captain, had lost her erstwhile comeliness, specially since her baby died, but she had started regaining her looks. She was a good woman and had suffered a lot. One night she came to him and asked if she could lie by his side. He did not want her, but he said nothing and she took this as acquiescence. He was quite embarrassed when she began to make it manifest that she wanted him. Gently he indicated that he was not ready. She understood, nodded and went away, but she did not look for another man. She had obviously made up her mind that it was Midala she wanted. He fought hard to stop images of that most desirable woman invading his thoughts unbidden. She had high cheekbones and slightly sunken eyes, and an egg-shaped head which he found very attractive, but he thought that her full lips were her best features, vibrant and sensual. She was a strong woman but her breasts seemed small in comparison, and surprisingly long slender legs shot down from her ample behind. He easily imagined his two hands sliding up and down her frame in a sort of closing and opening flourish centred on her waist. He was a man with normal desires and knew that sooner or later he would not be able to resist her charms, specially as it was obvious that she had chosen him.

Missié de Fleury himself came for a visit the following week, and said he was shocked at the snail’s pace of this useless lot. He made a speech in that sense, which was translated by Antoine, and threatened severe measures. His eyes fell on Midala as he was talking, and he got Antoine to call him. Midala walked towards the big Missié eyes on the ground, and for no reason Victor de Fleury slapped him with the back of his hand.

‘That’s for your insolence, Cacapou,’ the red man said, ‘just remember who you are and who I am!’ Midala did not understand a word, and although he was boiling with rage, he kept his head down. The irate man screamed some more, and gave them some orders to the guards, whereupon three of them came towards the warrior, seized him and frogmarched him to a coconut palm and tied him there. He offered no resistance. They then took turns and gave him ten strokes of the whip each. The warrior thought that it was politic to pretend more pain than he felt, and winced dramatically each time the leather coiled itself round his bare bleeding back. He readily understood that whipping was not a punishment for slackness or for doing something wrong. It had two purposes, to show who was boss, but more importantly, to break the spirit of the slave in order to gain complete dominion over him. My spirit will never be broken, he promised the Spirits.

But his body was in a a sorry state, and that night when Matamba came to nurse him, he felt grateful and let her, and she knew that she had won. She rubbed his sores with coconut oil, and then began to caress him all over, and was delighted when he responded. He did not tell her that although she was the woman in his bed, in his mind he was lying with Rolena, who will forever be the woman in his heart, the woman who will welcome him when his time came, to travel to the Land Beyond.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Henning Leweke

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Henning Leweke

The fields near Sept Cascades had been cleared and were ready for cultivation but the cane cuttings had not yet arrived from the north. So, when a ship arrived in the half-finished harbour of Port Louis on the west coast, with cattle that de Fleury’s agents had bought for him in Madagascar, Midala and a party of other slaves with half a dozen armed guards were despatched to go fetch them and take them to Montagne Trois Mamelles, where his herds were kept. The men walked from daybreak until much after sunset, when they reached the new harbour town. They slept on the beach. Escape would have been possible, but Midala was still not ready for that leap in the dark. There is plenty of time for that, he told himself. Next morning, the cattle were disembarked, washed, watered and fed. There were forty of them, most of them severely ill-fed, with protruding ribs. Five had died during the crossing, for they had undergone a five day trip in their hold with no food and very little water.

It was early afternoon before they were ready to start moving. The team was quite expert at dealing with the bovines, and Midala was quite happy to follow the instructions of Georges Couillon, who had obviously been an accomplished cattleman back home. They went along at a brisk rate, and an hour or so later, cattle and men found themselves on the bank of the Grande Riviè Nord Ouest, a slightly more respectable river than the stream beneath the mountain. The cattle drank lustily, and the men cooked and ate their meals quickly. They continued along the bank of the waterway, and as the terrain was rugged and rocky, they had to proceed gingerly. Sunset saw them on the riverside and they bivouacked for the night. Couillon again proved himself a dab hand at what he was doing. The cattle were clearly disturbed after the rough crossing, and might have been nervous and unruly, but he went to each animal individually, patted them, talked gently to them, and instructed the men to do the same, and what might have ended up as an almighty stampede, turned into a peaceful night.

Midala was heartened by the almost complete absence of people on the road. It was easy to see why. There were hardly fifteen thousand people living in the island, almost all of them living in the settlements that had started springing up. Probably no more than two thousand were white men, and the rest were their offspring with black women or slaves, or so, Midala surmised from what he had heard. It seemed possible to hide in these ravines, with a proper river providing drinking water, as well as irrigation for cultivation of corn and yam. If there were just him and Matamba, it would be almost impossible for them to be detected, and if there were more, they would have to organise a watch. They could live a decent life like this for a long time.

Antoine told him that de Fleury was delighted with the team, as not a single mishap had occurred, not one cow or bull had escaped or died during the trek to Trois Mamelles, but naturally he said nothing to the men, except threatened to flog them for taking so long and wasting valuable time. Midala and his companions were kept busy doing a number of chores. A concern like de Fleury Estates with its multifarious interests depended on work rotation, and Victor de Fleury prided himself on his organisational skills. Sept Cascades was waiting for the right time for the planting of the cuttings, so some people were despatched to Flacq on the east coast where he grew tobacco, and others to Trois Mamelles to look after the cattle. Midala having been part of that successful team was picked for that, but Matamba went to Flacq. Midala did not realise how much he would miss his new woman, but he had no choice in the matter. He did not feel the time was ripe for a dash to freedom, and would bide his time

The work on the cattle ranch was neverending, but it kept him from thinking too much of his wretched condition. He missed Matamba, and did not welcome the advances of other women. He wondered whether he was falling in love with the woman. He hoped not, as he would not want anybody to take Rolena’s place in his heart. Every night he would think of his dead wife and recall the many good moments the two of them had spent together, but often as sleep began to take over, Matamba and Rolena became confused in his mind.

When it was time to start the sowing, he was sent back to Sept Cascades, as was Matamba. She had pined for the return of her new lover, and their reunion that night was passionate and fulfilling for both of them. Why can we not be always together? she asked. Why do we have to be slaves? The man replied.

As he was a cautious man, he had not talked about the ravines and the river to her, or to anybody. Surprisingly the one person he felt the urge to open up to on this subject was Antoine although he knew that the older man had the trust of de Fleury, but he also knew that he would never betray anybody. Antoine sometimes stopped for the night at Sept Cascades, sleeping in the shed with the others, and one moonlit night the two of them were sitting under a flame tree outside, smoking their pipes when he said a sentence that he had rehearsed many times before.

‘Colibango, have you tried to run away from here?’ Antoine froze, looked at him obliquely and frowned.

‘Don’t talk like that. Some questions are never asked. And please don’t let them hear you call me Colibango, Midala… eh Cacapou.’

‘Have you?’ he insisted. The older man shook his head and stayed silent for a bit.

‘Like everybody I have thought of it, but there are so few places to hide, I told you that on the day you arrived. This is a small island.’ After a pause, he added, ‘What can you do with a bad leg anyway?’

‘I know one or two,’ Midala said, ‘I mean places to hide.’

‘I also told you about the Anti-Maroon Units, they are —’

‘The place I am thinking of, it will be easy to play hide and seek, you see, when we went to the harbour —’

‘No don’t tell me any more, for I might blurt it all out if I am flogged. I am an old coward.’

‘I don’t think you’re a coward… or old… but…’ He thought it best to leave it at that.

‘There are places… like the gorges in Black River, Le Morne Brabant,’ Antoine said unexpectedly. He was obviously surprised to hear himself utter these words, ‘Eh, and… there’s water there, and grottoes, I am told… and you could grow corn and there’s plenty of cocoyam growing wild… and there are fruits… but the Units will be sure to look there. And you must have seen the Grand River… there are ravines there… also a good place to hide, but again, they will look there… I could name a few other places… but I don’t want to encourage you… if they catch you…’ Antoine’s voice was near cracking with tears threatening to cascade out, ‘My brother Combasso… my uncle’s son actually, he ran away. They caught up with him on that mountain in Port-Louis… the Citadel… he was half starved and sick, they dragged him up to Trois Mamelles, here… you’ve seen the tamarind tree? They tied him there for two nights, and on the third morning, Missié Victor summoned everybody to come and watch. He made a speech. ‘I am not a bad man,’ he said. Antoine stopped here, unable to continue for a big lump his throat. But he took a deep breath.

‘Yes. I am not a bad man, Missié de Fleury said, I am a God-fearing Christian, I go to church every Sunday… I feed you, I clothe you, I give you a roof on your head… out of the goodness of my heart, but I expect obedience. One hundred percent, you understand. You savages cannot understand this, as you have lived in the jungle, eating each other, respecting no laws, human or God’s, so you need to be taught a lesson that you cannot forget. The law of this country is that a runaway has to pay with his life. I am going to carry out this execution. Antoine… he called me.’

Here Antoine was unable to restrain himself, and his tears rolled down profusely. Midala put his arms around him and hugged him.

‘I get the picture, you don’t have to talk about this.’

‘No, I want to,’ said the older man almost aggressively. ‘Antoine, here, take this, he said. And he gave me the whip. You’ve seen his whips, they are made of dried cow hide. You start… as he is your cousin… show them that you agree that your cousin deserves what he is getting. I told you that I am a coward… I knew that if I refused, I would end up like Combasso… so I nodded and took it. Combasso… he was younger than me, it was my duty to look after him, and there I was, helping to kill him. What was worse Midala, was that I could not show my sadness and anger to the boss, or I might have lost his trust… and I needed him to trust me… to think that I am on his side at all times… that’s the worse part of slavery, your survival becomes more important than your soul… And I knew what I was expected to say, and I said it… Pierre… yes, that was Combasso’s new civilised name… was ungrateful master, you gave him everything and he… spat in your face…’

‘Tell him he deserves to die,’ prompted de Fleury.

‘I opened my mouth, but no power on earth was going to make me.’ Missié Victor took two steps in my direction, and I began to fear for my life and instinctively put my hands in front of my face, but he looked at me incredulously.

‘What was I thinking? He’s your flesh and blood…’ He shook his head sadly and took the whip from me.

‘He made someone else do the job, but I had to watch…’ the limping man whispered. And Antoine’s tears were now beyond control, and he was unable to continue. He cried like a child, like a woman who has just seen her child killed, but most of all he cried like a man who had suddenly remembered how to cry.

‘I understand,’ said Midala, ‘he’s such a hateful man, how you must hate him.’

‘Me hate him? No, Missié Victor is my father and my mother, my god.’

‘What are you saying, Colibango? How can you not hate him? Do you have blood in your veins?’

‘I have blood in my veins. But that man… listen, when we landed in Mahébourg… I was more dead than alive, I had diarrhoea, but worse, during the storm I had broken my leg… you know, the ship rolls and you are chained and lose control, you are thrown all over the place —’

‘I know, so many people were crushed to death.’

‘Anyway, my leg was broken… we had just landed, and there was this colon shoving and pushing me. I had fallen down and he was kicking me when Missié Victor saw us… he came towards us and slapped the colon in the face, hard like… Can’t you see the man has a broken leg? He took me under his wings, ordered some men to look after me, treat my leg, threatening to flog them if anything happened to me.’

‘Really!’

‘Yes. Go figure.’ He smiled wanly.

‘And he came to see me everyday, bringing me a bottle of rum and ham and eggs… he then decided that as I was not completely fit, I would not be able to do any hard labour, and decided that I could do a good job as a sort of go-between between him and the workforce. So how can I hate him? He saved my lie, I owe him everything.’

Was this the reason why the white man seemed to treat Colibango with something like respect? It was more than respect, Midala had seen clear evidence of affection. Midala knew that when someone did a good action, the gratitude this generated was two-sided: first, the recipient felt grateful for obvious reasons, but the benefactor feels gratitude for being allowed to do something which made him feel good about himself. Being kind to Colibango was De Fleury’s certificate of humanity that he awarded to himself. Since he had one, it did not matter how he treated the others!