The cane plants now growing lustily in Sept Cascades provided an impressive sight to visitors. The luxuriance was not unexpected, for the land had been fallow since it rose from under the ocean nine million years ago as a result of a volcanic cataclysm. The cane stalks in the ground were firm and dark scarlet, and the leaves fluttering in the breeze, like a green sea, the colour of jade. Flourishing above the leaves, the marble-white bloom with a soupçon of the palest pink shone proudly in the tropical sun, swaying gently in the breeze.

There is always a period of inactivity prior to the harvesting or coupe, and people who had gone to tend cattle or grow tobacco in de Fleury’s other outposts began coming back, in readiness for the back-breaking task of cutting the cane with a machete. All of a sudden there were people hacking at the stems, denuding the sticks of their green stalks and loading them on oxcarts, and Midala knew that this hive of activity would provide a good smokescreen when preparing his breakaway. He had not got to know any of his fellow slaves well enough to risk confiding in them, so it was just going to be him and Matamba. After his attempts at organising escapes on the Coimbra, which had ended in catastrophe, he was not sure if he wanted to be responsible for any further tragedies. Besides deep down he must have known that two people on their own had a better chance of escaping recapture. He had carefully noted landmarks when he had accompanied Couillon to Port-Louis, noted the position of the sun at various times of the day. He had been a hunter in Inhambane since childhood, and as such had developed the skills necessary for guiding himself by land features and stars. To his amazement, on the eve of the day he had chosen for the breakaway, Antoine asked him to join him for a smoke behind the shed. I have got something I want to give you, he said, it belonged to Combasso. He gave him a flint and steel striker. You never know when you might need this, he said curtly, and not waiting for a thank you, he hobbled away on his limping legs.

On a Sunday morning, after mass, attendance to which was compulsory, he and Matamba quietly slipped away, collected the few things which they had been hiding in the bush over the last weeks, among which there were a battered old cooking pot, a kitchen knife, some dried salt-fish, some manioc, and took off. They walked briskly towards the mountain. It would take some time before they were missed and a lot longer before anybody would inform De Fleury and the Unit. In any case it would not be difficult to play Hide and Seek with them in the thickets that flourished all over the place. Soon the Trois Mammelles was behind them, and they took that as a sort of victory. They kept walking until sunset, when the rains started. They had reached Tamarin and decided that they would stop there. They were in no hurry. They found shelter under a massive strangler fig, huddling together for warmth, for the in May, the temperature drops quite a bit at night. Next morning, some monkeys on the strangler began hollering, and throwing sticks and pebbles at them, and they got up. Matamba manifested her amusement at the antics of the apes by screaming with laughter; Midala smiled happily — even at his happiest he rarely laughed — Rolena used to tease him about this.

He collected some twigs of which there was an inexhaustible supply, and proudly lit a fire by using Antoine’s gift, and made tea. They drank it with sugar, from a small bamboo cup they had brought along with them. At home in Inhambane, they used wild honey as a sweetener, but this was a sugar island.

They walked briskly for a couple of hours. In the distance they could see the sea and the new but still incomplete Port-Louis harbour which Midala had seen when he went to collect de Fleury’s cattle. They were not surprised, and considerably relieved when they had not encountered a single human being since they left their camp. They heard nothing but their own footsteps, birds twittering, monkeys howling, lizards tut tutting, and in the night, frogs croaking and cicadas chirping, leaves rustling in the breeze. Matamba said that if she closed her eyes, she could also hear the sound of the stars. He had not felt so lighthearted since the times when he was courting Rolena. It was mid-afternoon on the next day when they heard the flow of the river. They could contain their excitement no longer, and rushed towards where that most welcome of sound was coming from. Suddenly they saw the ravine with the river flowing below. It seemed narrower than he remembered, certainly not wider than the length of a mopane tree, ten tall adults standing on each other’e shoulders. They scrambled down the steep bank, unconcerned by scratches to their limbs and face, and exhausted by the effort, but ecstatic at finally becoming free, they threw themselves on the ground, the sun in their face and relished the moment. They found a nice pool and swam and gambolled in it like teenagers, after which they made love. Until now, they had always made love furtively, embarrassed by the presence of forty other couples, often doing the same thing. Even if no one could not see what the others were doing in the dark, the ubiquitous ‘hoos’ and ‘haas’ were off-putting. This was the first time they indulged in their passion without any inhibitions, as free individuals.

They went exploring the area, to discover what, if any, were the sources of danger and plan a strategy on the how to avoid detection.

It did not take them long to discover a grotto which seemed ideal for them. The Spirits were looking after them. Just outside there was a tree of Mother’s Best Friend, the Drumstick tree — the best possible food in existence. We need never go hungry now, Midala said, the Spirits mean us to prosper. They had found their new home. Next they set out to discover where they could grow the seeds that they had brought along, and although the terrain was pretty rocky, they found patches where the soil seemed dark and fertile. They had tomato seeds, kalalu, beans, chillies, chou chou, pumpkin. They put aside half the seeds, in case they failed to sprout for some unknown reason, or were destroyed by pests, insects or birds.

He was satisfied that as they were well hidden by the luxuriant vegetation deep in the ravine, there was little risk of detection, unless it was suspected that they were there and a party was despatched to seize them. But they knew that with the coupe in full throttle, De Fleury would not be able to spare men to join the Anti-Maroon Unit, but they knew that Missié Victor often acted impulsively, and thought it best to be on their guard at all times.

There were plenty of snails. They collected them, scooped them out of their shells and roasted them over a wood fire and found them better than those back home. Then they made their most serendipitous discovery: cocoyam, the husband of all yams, growing on the river bank, just like at home. In Sept Cascades, people called their heart-shaped green fans “brède songe”, dream leaves. They were delicious when cooked with a piece of fish, for on its own it gave one the itches and caused rashes. Matamba was not over-fond of the brède songe though. To her, the best thing about it was how drops of water coagulated on its waxy surface to form a small ball of liquid silver. You’re just like a child, her lover teased her. When we were children, she told Midala, whenever they did not listen to their parents, they would moan. Whatever you tell the children, they would say, is like water on malanga. Midala smiled, nodded and added that in their village they used to say whatever you said to us children went in one ear and straight out of the next with the speed of a cheetah.

For the best effect, one needed salt and oil to cook malanga leaves, and they had neither. If only they had thought of bringing some salt… Still it filled space in an empty stomach. Unfortunately their supply of dried fish was limited, as they had only been able to deviate a small quantity, but they knew that living by the riverside, it would not be long before they discovered the means of catching fish. They peered into the water where it was relatively still, and indeed saw some fish there, but catching them was another matter. They found a few dried-up breadfruits still on the branch, and ate them boiled, but unfortunately, again unsalted. For some time they ate what was available, one day brède songe and cocoyam and next day drumstick leaves soup and roasted snails, and did not starve. There were wood pigeons but like the fish, they needed to be caught first. They hoped that it was a matter of time before they found the means of doing so.

Sisal grew in profusion in the area, and before long they were making yarns. Matamba did a very delicate job, and ended up with twines of incredible fineness and strength.

By now, the seedlings had begun to prosper, and the runaways felt optimism rise in them. They made some blankets with the sisal fibres, and if they were coarse at first, you soon got used to the scratching. They made fishnets and although the fish were elusive at first, they were more easily able to catch very small shrimps which they cooked with the brède songe to excellent effect, but the lack of salt made it difficult to enjoy fully. Matamba often expressed regret at this. Everyday they would look at the sea, and dream of a properly salted meal. It did not seem all that far away, but they were not going to take their chances. Still there was very little traffic in the area, except around Port-Louis, which they could see in the distance when they went up the ravine, so…

They discovered some coconut palms growing beyond a ridge they had not ventured beyond until now, and this brought a new dimension to their diet. Grounded coconut provided the oiliness that enhanced sauces. Patiently Midala detached the hard shells from their fibres, and working on a shell for hours, with his prized knife, he managed to make bowls and containers which proved very useful. They were able to make coarser ropes with the coconut fibres. They tried various spots in the river for fish, and finally found what must have been a rich breeding ground and gathering fish became a simple exercise. Back in Inhambane everybody dried their catch of ngaa in the sun for use off-season, and they did the same thing in their new abode.

One thing leading to another, they made things to wear, and got used to them after a while. As he did not have any proper tools, Midala used his trusty knife to fashion out bits of wood in all sorts of shapes, and ended up by putting them together to make stools and tables. Matamba made footwear for both of them, and they thought that they were living quite comfortably. Unless there were unforeseen changes, they thought, they could live comfortably and in freedom for years to come.

They found lots of fruit trees, and expected that when the warm weather arrived, they would have plenty of mangoes, guavas, jackfruits and some other fruits they did not have in Inhambane.

Everyday they ventured a little bit further, and were satisfied that there was not a single dwelling within shouting distance of their domain. They knew that even taking all possible precautions, even if they could stay out of sight, there was no way of stopping smoke attracting attention. This was what made them do their cooking at night, but as they felt more secure, they began gradually dropping their guards. They discovered the early stages of a track at some distance from the grotto, which they imagined the cariole of the masters sometimes used, but so far they had not seen or heard any traffic.

One day, he gave the woman he now loved more and more the fright of her life by suggesting that he would go fetch her some sea water so they could really enjoy some saltiness. Are you mad? she said, do you want to be caught? You’re right, it’s too dangerous, he said negligently, but already he had a plan.

There was a measure of recklessness in the old warrior which he could not always control. He had decided that he would attempt a midnight sortie. He had the faculty of waking up at the time of his choosing, and one full moon, three hours before dawn he quietly slipped out of bed with two empty coconut shells aiming for the shore which he easily reached before dawn. There was a very small settlement of less than ten huts, probably housing some freed families. There was also an official looking building, probably the army hospital he had heard about. There was not a soul in sight, but he could see smoke in the distance. Or it might have been morning mist. What looked like another larger settlement unexpectedly emerged from the dark, and he navigated very carefully round it. When he arrived at the beach, as he expected, there was not a soul in sight. First light enabled him to peer in awe at the beauty as he watched the glistening waves. He closed his eyes in order to dwell upon their music as they gently crept in and finally crashed on the sands. Suddenly he could not resist going in. Swimming in the river was nothing in comparison. He swallowed a big gulp of sea water, and although it was more bitter than salty, he relished it. He then filled his shells with sea water, and was on his way back. The first ray of the sun was beginning to peep in timidly when he heard a noise, and saw three carioles coming towards him. He was in a field with no place to hide, but a strangler fig tree, and he waited behind it for the carriages to go away. However, to his amazement, they stopped, and some men in pith helmets and shiny knee-length boots carrying whips came out with a handful of semi-clad blacks, carrying bundles and cases. There was no way to move and avoid detection, so there was only one thing to do, the Spirits be blessed. He carefully put his two coconut shells full of sea water beneath the tree, eased himself as he knew that it might be some time before he would be able to do it properly, and using a hanging root, he hoisted himself up, sat on a branch, protected from view by the thick foliage, and he did the only thing possible, watch the men at work. The men were obviously carrying out some preliminary work in that very field. No doubt the early start was to avoid the punishing sun. They started working in an enclosed area of the field, measuring and digging out huge rocks. They worked without stopping, for hours, until the sun started going down, and he was in agony, hungry, hot and thirsty, waiting for the men to finish, and when they finally stopped, they did not seem to be in a hurry to leave. He had worried about Matamba all day long and expected a right telling off when he got back to her. She was a good woman, and the wise Rolena would not mind about them being together when she watched them from the Good Place.

The man who appeared to be the leader finally ordered his men to stack the rocks in a neat pile in a corner, and this took over an hour. He stayed on the tree until sunset, and when the work force had finally finished their work, they got in the carriages and drove away. He waited for them to be out of sight, came down but in his hurry, he forgot the sea water. He had walked for about half an hour when he suddenly remembered, and went back to get his coconut shells. There was no danger now. Matamba’s eyes were red with weeping; she clung to her man, beating him on the chest with her fists and hugging him at the same time. She was trembling all over, and it took a while before she regained her composure.

‘I’ll cook you some pigeon,’ said Matamba between sobs, crying and laughing at the same time, ‘and tonight we will have our first salted dish since we ran away.’

She explained how she had imagined the worse and how, distraught and frustrated, she had angrily thrown a stick at some poor pigeons and, incredibly, it had hit one.

The two runaways lived like this for some time. Although they both loved malanga cooked with shrimps or fish, and drumstick leaves in all its forms, specially cooked with coconut- a recipe Matamba had invented- they were beginning to hanker after other things. Fortunately their seedlings started bearing, and there was never any shortage of variety. It was clear that one could throw a million sticks at some pigeons and not hit any. The Supreme Spirit had intervened because He had wanted to comfort Matamba. Now, the warrior set about devising the means of capturing pigeons. He got her to weave a basket with sisal fibres and placed some left over food under it, and when the pigeons came to eat, he pulled a piece of string he had attached to it, causing the basket to trap the unsuspecting bird under it. They found some thick bamboo one day, and he cut a few of the thickest ones, and after a lot of hard work was able to make containers of much larger size than coconut shells. Matamba frowned when he brought them to her as she was sitting on a rock with her feet in the water.

‘Why what’s the matter with my bamboo bottles?’

‘You’re not thinking of going back to the sea to collect sea water, are you?’

‘I know the route now,’ he said, ‘ and above all, I know how to avoid the danger.’

They argued for a bit, but he assured her that there was no danger at all, and promised that he would be ever so careful. Again some hours before dawn, he set out, promising that he would be back early in the morning. This time he was true to his word. The people who had been working in that field had come back, and were building what looked like a big stone building, and some of them seemed to be sleeping on the site now.

‘That must have been dangerous, they could have seen you?’ He grinned and shook his head. She stared at him in admiration, for this was one of the rare occasions that she had seen him smile. No, it’s not dangerous, once you know what to expect. This was a principle he had learnt as a soldier. Intelligence was much more valuable than weapons

Their confidence in their new environment grew from day to day, and they began venturing further and further away, never dropping their guard. Sometimes they saw carioles in the distance, negotiating the rough terrain; rarely they saw people on foot. One afternoon, they espied a man and a woman, clearly white bosses, walking in a leisurely manner, arm in arm, and they tailed them cautiously. They ended up in an alley planted on both sides by ornamental palm trees, at the end of which they saw a newly built mansion. It had a large open verandah and was freshly painted white. As there was plenty of luxuriant vegetation, they found it easy to remain unseen. There were some black slaves working in the garden, two men and three women. They watched them in silence for a time, taking comfort in the knowledge that there were people nearby they could ask for help in an emergency.

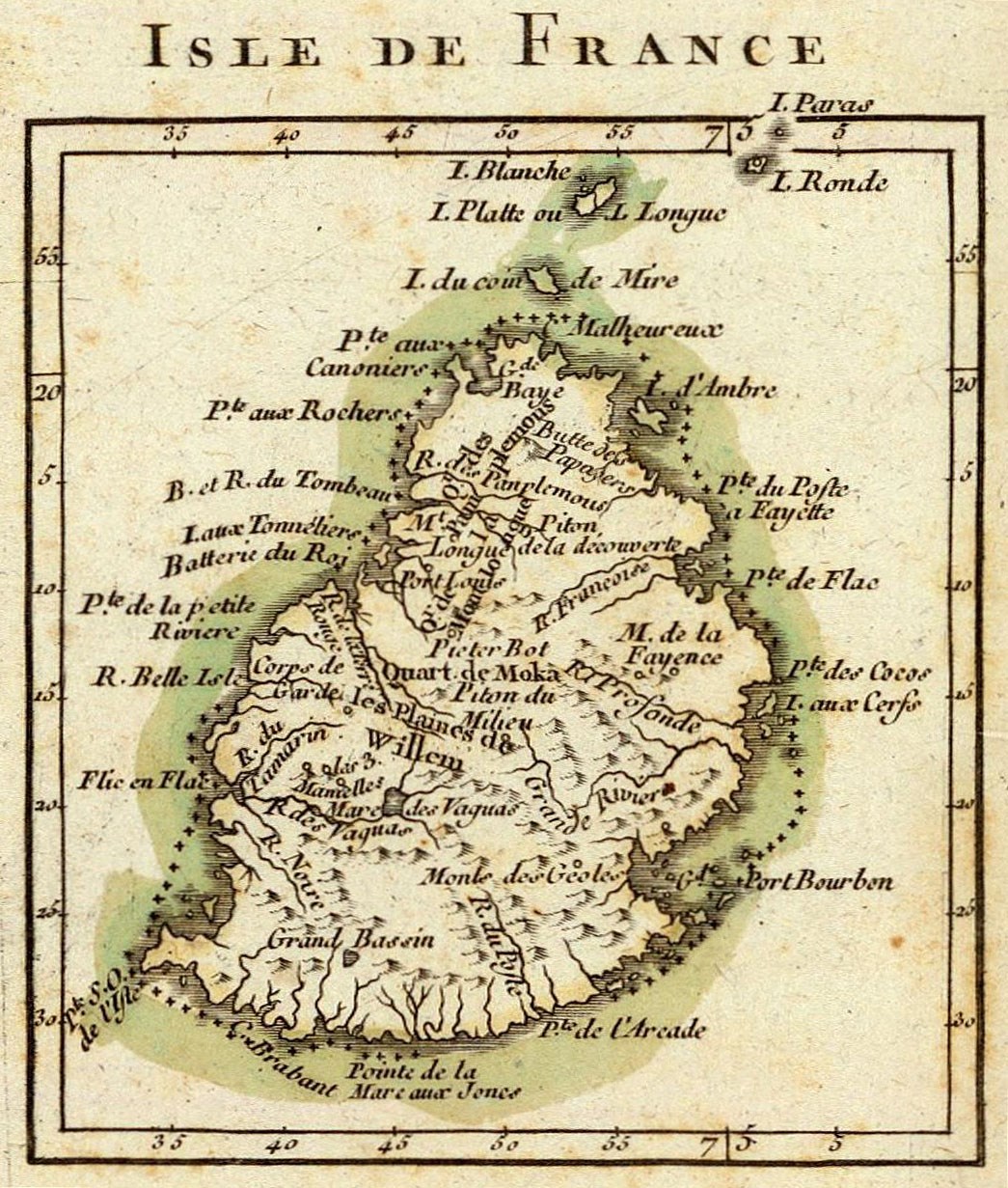

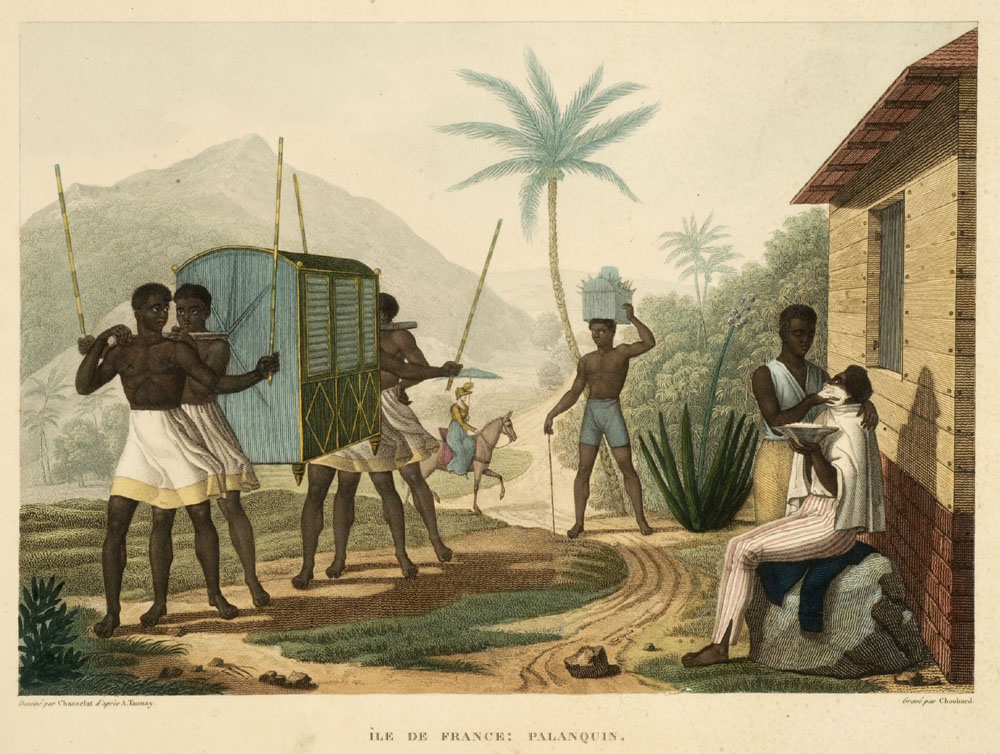

Photo Credit:

Carrying a Sedan Chair or Palanquin, Ile de France 1818 (Public domain, copyright expired)

Photo Credit:

Carrying a Sedan Chair or Palanquin, Ile de France 1818 (Public domain, copyright expired)

On the next day they decided to go back to the mansion, and as luck would have it, they saw a cariole coming towards them. They hid behind a tamarind tree and saw the white couple they had seen the day before. They guessed that the slaves would be on their own, and decided to seize the moment. They made their way inside the grounds and hanged around for a while amid the shrubbery, waiting for something to happen; they did not have to wait long. A round little woman emerged from the house and made for the garden where there were lots of vegetables, and they watched her collecting beans in a basket. Matamba suddenly took a few steps in her direction. The round little woman was humming happily, committing the pods to her basket in a comical manner, tossing them with a flourish, unaware of the alien presence. Matamba coughed gently, and the round little woman was so taken aback that she dropped her basket and began running away, as if she had seen a ghost.

‘Stop,’ said Matamba in Chopi, ‘I am not a ghost, I am… Matamba.’ The woman stopped, turned round to face her and looked at her in disbelief, opening her large eyes wide. How could she not be a ghost? She seemed to be telling herself.

‘I am a runaway slave, a maroon.’

‘Ayo,’ she said, and shouted in Shagaan in the direction of the house, ‘come over here, there’s a maroon… she speaks Chopi…’ Matamba got the gist of what the woman was saying, and was terrified; who was she calling? Were there other white masters inside? Midala, who had stayed hidden emerged from the bush, increasing the confusion of the small round woman. A small army of black slaves came out of the house, brandishing broomsticks, machetes and iron rods.

‘We are not dangerous,’ Midala said, ‘we mean you no harm, we’re runaways.’

A grey-haired man with only one eye nodded wisely.

‘We suspected there were runaways in the ravine, when we saw the smoke; we even talked about it.’

‘But then no more smoke…’ said a thin woman with a child on her haunch.

‘But of course we said nothing to the masters, we don’t wish you any harm,’ said a woman with a child on her back.

The pair knew that the battle was won, that there was nothing to fear. Without further ceremony, they all sat down on the dry grass like long lost friends. They were Shangaans and not Chopis, they explained, but the wars between their two nations were back there; here we are all cousins, they said. They explained that the masters had gone to Port-Louis for the day; he was the son of the richest man on the island, some sort of chief. They were called Monsieur Alexandre Taillefer de Sauvigny and the lady was Madame Georgette. They had a little boy called Bertrand, but he lived with his grand parents in a place called Moka. The lady is the daughter of the governor of the island. The name of this house is Mon Château, they added.

‘I am sure you must be living under difficult conditions,’ said the grey-haired man whose name he told them was Jacques Grenouille.

‘Midala had to risk his life to get me some sea water,’ Matamba said, and told the story to a rapt audience.

‘Oh yes,’ someone said, ‘we have heard that they are building a factory to make sacks with the sisals near La Pointe aux Sables.’

‘You must be short of pots and pans, kitchen things,’ the woman with the child on her back said, ‘we can give you all you need; we have everything here, and nobody knows how many; the lady never sets foot in the kitchen anyway.’

They were delighted when someone proposed to get some food from the kitchen, and came back with bits of goat meat and manioc; they ate and drank heartily, and someone asked why they had preferred to leave the comfort of their master’s house to brave it in the woods, and were shocked when they were told about the conditions in Sept Cascades, the back-breaking work, the whip and the insults.

‘Here,’ Grenouille said, ‘the master and the mistress are very nice and the idea would never occur to them to whip anybody.’ Besides, they explained, Monsieur Alexandre has said that as they belonged to his father, he could not free them, but that one day, he would do just that. They were not all delighted at that prospect.

‘This is a strange country,’ the round little woman chipped in, ‘we did not ask to come here, they captured us and took us here against our will; if the master returns us to our home that’s fine, but if they just tell us one day, look, you slaves are all free to do as you wish, what will we do.’ Jacques shook his head and tut tutted.

‘I have explained I do not know how many times, that when a slave is set free, he can find employment and earn good money and live where he likes, and as he likes, but not everybody is convinced.’

Midala and Matamba had clear views about this, but were sure that when the time came, everybody would seize their liberty with both hands and never let go.

The people of Mon Château gave them a large quantity of foodstuff, clothing and kitchen implements. Midala almost regretted that he need never go back to the sea to fetch salty water.

‘We’d like to come visit you in your… abode…’ someone said, ‘but we don’t think we are allowed to leave the perimeter of Mon Château.’ This made Jacques Grenouille cackle with laughter.

‘Proves my point,’ he said, ‘as free men and women, you would be free to go anywhere, there will be no boundaries -‘

‘He is right,’ Midala said. And they went back to their home, not for one moment minding the weight of their gifts.

Life after their visit to Mon Château became much easier, but Midala could not help feeling uneasy about the new development. No one was going to betray them intentionally, but something bad was bound to happen.

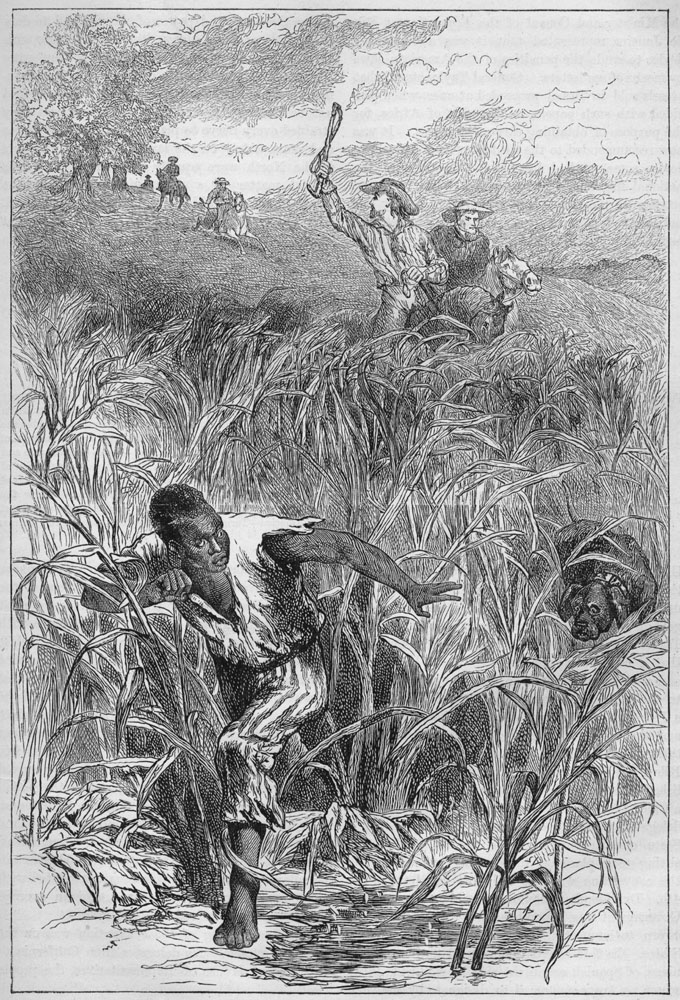

Photo Credit:

William Dobson Valentine "Valentine and Sons - Cane Cutters, Jamaica", 1891 (Public domain, copyright expired)

Photo Credit:

William Dobson Valentine "Valentine and Sons - Cane Cutters, Jamaica", 1891 (Public domain, copyright expired)

At the end of the cane-cutting season, de Fleury summoned his guards and ordered them to find the runaway couple or else… As he had guessed, the Anti-Maroon unit had been completely useless. Antoine was again included in the party. Later, when he was helping the master remove his boots, he felt emboldened to emit an opinion.

‘Master, there are so many places for a runaway to hide, where shall we start? We’ll never catch them, it would be like looking for a cricket that has lost its song in a cane field… I mean the chirping might have led us to him…’

‘The first place would be the Citadel; remember that fellow who was hiding there, before we dealt with him?’ How can the man be so insensitive as to mention him, thought Antoine.

‘Yes, master, but there are so many places,’ insisted the slave.

‘Where would you look?’ asked de Fleury; Antoine winced. What if he mentioned a place and Midala just happened to be there? It would be like he was betraying him.

‘Master, I have hardly been anywhere, I am an ignorant slave, I have no idea.’ De Fleury laughed.

‘Suppose… you decided to run away… where would you go?’ He had thought of the Black River Gorges once.

‘Well, he began,’ but stopped immediately. No, he was not going to say. He took a deep breath.

‘Master,’ he said smiling, ‘why would I want to run away; I am very contented here, serving you…’ De Fleury nodded happily; why didn’t the others realise that he was a fair man, and that all he wanted was for them to do as he said and they would never suffer any ill treatment.

‘The Black River Gorges would seem like a good place to search, and the ravines… the two Grande Rivières, there are some grottoes on the coast. The island is small… it shouldn’t be too difficult. If I was not so busy, I’d come myself, it should be good fun, better than deer hunting, eh.’

A few days later, four guards, three fresh recruits from France, a Créole, and Antoine, set out on their mission to put an end to Midala and Matamba’s dash for freedom, under the leadership of Mr Catard, a senior colon. They scoured a good few places where runaways might find a refuge, but found nothing. Finally the party arrived in the vicinity of Mon Château near the hiding place of the couple. They were received by the young master and his wife, and they in turn ordered all their retainers to appear in front of the search party. The Shangaans were shaken and when they denied with unnecessary vehemence that they had seen the slightest unusual thing, never any smoke, may their tongue drop out of their mouths if they were lying, Antoine immediately knew that the couple were in the ravines below.

Catard suggested that they searched the ravines, whereupon the crafty Antoine casually mentioned that according to him that would be a waste of time, for if the runaways were anywhere near here, the Shagaans would have seen something, some movement, or smoke. Catard was on the point of agreeing, but changed his mind.

‘We are running out of places to look,’ he said, ‘if we go back empty-handed, the boss is going to have the skin off our arses,’ adding ‘and if he heard that we did not go down the ravines here, he will think we failed in our duty… I think we had better go and see for ourselves.’ So it was decided to go down the ravines.

Perhaps because he had guessed right, Antoine kept seeing signs of human presence, debris of sisals, mango stones, feathers, and such things. At one point, one of the guards stumbled on some tomato plants and gave the alarm.

‘Right, our slaves are in the area,’ the leader said, ‘let us leave no stone unturned now… come on boys, open both your eyes wide, and your ears too.’

Antoine burst out laughing, ‘here on this island, tomatoes grow wild,’ he said, ‘didn’t you know that?’ Fortunately this was accepted by the colon who had grown up in a town. Still, they looked and saw nothing. He was running out of ideas, and if the white men discovered that he had been trying to put them off scent, de Fleury might vent his anger upon him. Suddenly they came across the charred remains of a wood fire, and Antoine was sweating all over. Fortunately it was Catard himself who came to the rescue.

‘I know what this is,’ he said, ‘people come fishing here on the riverside, and they light fires to heat their food.’ Everybody agreed, except the crafty Antoine who demurred.

The fugitives had received the shock of their lives when they had seen the armed party scrambling down the ravines; their game was up, they had thought. There was only one thing to do, and that was to go inside their grotto and wait for the worse. They were not planning to fight against men armed with guns. They held their breaths, holding each other for comfort and waited. On his own, Midala would have flung himself on a guard in the hope of disarming him and then use his weapon to fight the others, but that would be madness under the circumstances. The party passed just outside the grotto, but the camouflage must have been good, for no one stopped, and finally they gave up and left. They spent another week chasing shadows, and to their surprise the normally irate man said that it was indeed a tall order, just like looking for a cricket which had lost its song in a sugar field. But mark his word, he warned, that rascally pair was bound to commit a mistake, and when they do, he will be waiting, adding his usual cryptic phrase, ‘they are losing nothing by waiting!’

The pair decided to go to Mon Château on the next day to share the tale of their narrow escape with their new friends. They waited in the lush vegetation to make sure they would not run into the masters, and true enough the cariole with the young couple drove past, and they rushed to the house. They were received like long lost friends; their Shagaan hosts could not do enough for them. Midala did not say much, but Matamba regaled her audience with the story of their narrow escape. The masters were on their way to Moka, and would not come back for a few days, so they had the house all to themselves, but they were bringing back the brat Bertrand with them. Everybody ate and drank like kings, and although the pair were invited to spend the night at Mon Château, they preferred to “go back home,” as they put it.

The Taillefer de Sauvigny returned in a week with the boy Bertrand. It turned out that he was fanatical about fishing, and the moment he arrived home, he began pestering his parents to take him fishing in the river. Monsieur Alexandre was not too keen, but Madame Georgette begged him to humour the boy. So father and son set out one morning and went down the ravines to the river bank. Midala and Matamba caught a glimpse of them scrambling down, and watched their progress with apprehension, when suddenly, a branch to which the boy was hanging snapped, and he began rolling down the slope of the ravine, and landed in the water, as Midala knew he would. Alexandre began shouting “Au secours, au secours!” but as he scrambled down in panic, he slipped and caught his leg in a protruding root and was instantly immobilised, possibly with a broken leg. Midala watched his face contort in agony before it changed to an expression of horror, his son could not swim. Midala rushed out without thinking and hurled himself in the torrents, swam to the boy, grabbed him and dragged him to the bank; fortunately the boy was more scared than damaged. Monsieur Alexandre watched in amazement as this saviour appeared from nowhere to save both him and his son.

The fugitives were apprehensive; their cover had been blown. Although it was clear that Monsieur Alexandre was not going to do anything to harm them, the boy Bertrand was only seven.

Photo Credit:

Edmund Ollier, Cassell's History of the United States (London, 1874-77) (Public domain, copyright expired)

Photo Credit:

Edmund Ollier, Cassell's History of the United States (London, 1874-77) (Public domain, copyright expired)

The inevitable happened, and Midala and Matamba were rounded, put in chains and unceremoniously carted to Sept Cascades. He knew that de Fleury was watching him closely, so he decided to lie low for a while, but the white man, frustrated in his desire to whip the man to death because he had not weighed up the new governor yet; the bastard lost nothing by waiting; in the meantime he decided to separate the pair. No one, not even Antoine had any idea of where she might have been despatched to.

Midala had never given up the idea of escaping, but the military strategist in him was biding his time, accumulating more useful facts, determined that his next attempt would be a successful one. It took him all of a year to find the right moment. This time, Midala said to himself, no one will catch me alive. This time, swore the white man, I will move heaven and earth to catch the bastard, I will go looking for him myself, and when I do, he will have lose nothing for waiting!

Obviously Rolena had pride of place in his heart, but she was gone. The passion which had developed between him and Matamba had rekindled from embers that he had thought to be cold ashes, and a whole year’s separation had not cooled his passion for her. She was somewhere on the island, and he was going to do his utmost to find her. By now, he had a clearer idea of the lie of the land, and Antoine had told him a number of vital things. His friend had guessed that Matamba might be in Crève Coeur, where the master had a pineapple plantation. He also told him that as there was now an increasing number of freed ex-slaves scattered all over the island, living in small settlements, he might find refuge for a night or two, as to many of them it was a point of honour to come to the rescue of a runaway brother or sister; yes, even women ran away too. Antoine had told him of a champion escape artist called Azoline, who had escaped dozens of times. Antoine informed him about the code; it was surprising, he explained, that the Bourgeois class had not yet cracked it. If you are a runaway, and if you meet a black man whom you suspected of being a former slave, you rubbed your right eye with your index finger, as you passed him. If he does not respond, it means that he is not in the know, and had best be avoided. On the other hand, if he is willing to help, he will then rub his left eye to indicate this. When and if he does, you can follow him discreetly and he will give you food and shelter for the night, and will help you in many other ways.

With the bustle in the thriving establishment that Sept Cascades had become, it was not too difficult for a runaway to sneak out unnoticed, but it was well-known that most maroons were rounded up within one week. The slaves who made up most of the Anti-Maroon détachements having been promised freedom if they caught so many runaways, showed great keenness to rope in their fellow victims.

All the same, one Sunday morning, Midala quietly slipped away, heading for Crève Coeur. He walked carefully, avoiding public places where there were people about, although sometimes this was unavoidable, but to his relief, no one challenged him; Antoine had given him some decent clothing which made him look like a free man.

After four days, he found himself in the north of Port-Louis, whose importance was growing by the day ever since Governor Maupin had moved the capital there. A free man had advised him to go to Madame Agathe, an extraordinary woman who lived in Roche Bois; she was the mistress of de Metzger, a powerful Alsatian colonel of the Quatrième Régiment des Hussars, and had a string of powerful lovers besides. The lady, knew all about the suffering and humiliation of being a slave, having herself been only recently freed, at the instigation of one of her lovers. My body belonged to whoever could do her a favour, but my heart belonged to my enslaved people, she was reputed to have said. Although she was herself from Madagascar, she considered all slaves her people. It was a wonder that she had never been caught, for she was very open about what she did, feeding runaways, housing them, sometimes sleeping with them; everybody seemed to know about her habits, except the Colonel, who was besotted with her body; people said that she had given him her “dilo dire oui” to drink, and when you drank a woman’s dilo dire oui, you became her slave. If she tells you that black is white, you believed her, if she said that night was day, you’d swear the moon was the sun.

Midala had no trouble finding Agathe’s house, a handsome wooden edifice built at the back of a long alley in a spacious ground with luxuriant vegetation. It had originally been earmarked for lieutenant de Metzger’s, but he had reallocated it to the woman whose body could arouse passions in him that he had thought had long since expired. The fugitive was surprised to find that everything he had heard about Agathe was true. To his surprise, the big-hearted woman was also sheltering Azoline, of whom Antoine had spoken.

‘Go on, Azoline tell our guest how many times you have run away?’

The champion escapee smiled shyly and tried to work out the answer, and finally using her fingers, indicated to the man who had only run away twice that she had run away nineteen times in four years and a bit.

‘I have offered to send her back to Madagascar, but she doesn’t want to go,’ said Madame Agathe sadly, ‘she has her own reasons.’ Midala was surprised.

‘Do you mean you can arrange for —’

‘Sometimes,’ she said proudly, ‘if I can find a ship.’ Midala stared at her with admiration.

‘I can probably ship you to Inhambane,’ she said negligently. The warrior opened his eyes wide. He would dearly love to go back to his tribe, or whatever was left of it, find his boy Abo and his little girls.

‘Just say the word, and I’ll start working on it.’

No, tempting though it was, he was searching for Matamba; perhaps after he had found her, he might reconsider.

‘When you decide, I may not be around,’ she said sadly.

Next day, he was on his way to Crève Coeur. It was one of the most beautiful sights he had seen on the island, with rolling valleys criss-crossing each other, filled with a green and luxurious vegetation. There were a number of officious people supervising black men and women planting seedlings and removing weeds, and he had to hide until he found a good moment to address a wizened old man who could hardly stand on his two feet. When he addressed the man, he jumped with fright, and was on the point of running away, when Midala caught hold of his hand and stopped him. He asked him about Matamba, and it was clear that the man did not understand a word of what he was saying. It turned out that he was from Madagascar, recently arrived and had not yet picked kreol. But he offered to find someone who could help. He waited alone whilst the Madagascar man went to find a trusted kreol speaker.

When one was found, he greeted Midala with cautious friendliness, and said that as far as he knew, a woman fitting the description, and her baby had been taken away to another place, but she was called Madeleine.

His first thought was that it could not have been her; Matamba was not carrying his baby, or was she? He would go back to Agathe to ask for her help; she had many friends, and if anybody could find a cricket with or without its song in a cane-field, Agathe would be her name.

Reluctantly he turned his back on this beautiful place, and directed his steps towards Port-Louis. In Terre Rouge, which was a hive of activity because of the mining of iron ore going on there, Midala thought that he would easily pass unnoticed. But he was wrong. He was picked up and taken to Trou Fanfaron, where he was thrown in jail, pending a decision about what was to be done with him. De Fleury demanded that the culprit be handed over to him; he would cut off his ears and brand him on the shoulder with a fleur de lys, as was his right. He was convinced that that was the only way to deal with the recalcitrant. However, governor Maupin decided that the man was an ideal candidate for the Bagne, specially designed for receiving grands marrons, habitual runaways, and as yet, Victor de Fleury had not found any hold over his new excellency.

He was therefore delivered to the Bagne on the quayside in Port-Louis. It was His Excellency’s stated ambition to make this the most escape-proof establishment on any French territory, and to this effect, he had hand-picked Colonel Grapouille to be his representative on earth, naming him Surintendant du Bagne.