Midala had stopped feeling the pain in his ankle and wrist, but what was worse was that his whole body felt numb. His unjustified anger at Bomo the carpenter, the fellow he was chained to at the legs and the wrists, his twin, as he thought of him not without bitterness, had gone after he had repeated to himself that the poor man had not chosen to be tied to him. He had kept telling himself that Bomo had as much right to be angry with him, for whatever discomfort was unwittingly inflicted upon one of them, he had no choice but to instinctively react to the inevitable pain generated under the circumstances in order to minimise his own. He was surprised to discover, by his body language and the expression on his face that the carpenter bore him no grudge at all. He is a better man than me, he had thought. More in order to atone for his sullenness than for enlightenment, he whispered the blindingly obvious information, ‘I think we are being taken to the ship’. This earned him an immediate hit in the ribs by the mute mulatto guard. Midala felt the sharp pain, and would have been minded to jump on his attacker and beat him to a pulp had his movements not been restricted.

The ship could sometimes be seen in the distance when the vegetation and the rocky reliefs permitted. The sea ahead was visible as a pale bluish-green blanket with white embroidered patches where two or more waves collided. A gentle breeze somewhat mitigated their misery. Do you know where we’re going? asked Bomo under his breath, coughing slyly to disguise this infringement of the rule of silence, Midala shrugged. The mulatto saw nothing.

Bomo was almost the same build as him. The captors knew exactly how to pair the captives in order to convey them from the point of capture to the point of delivery most efficiently. The two men had known each other, but they had never had much intercourse, Bomo being a humble carpenter who earned his living making dugout canoes and wooden implements for pounding yam, stools, tom-toms and beds. He lived in his hut at the far end of the village, near the river, with his two wives and six children. He had no idea what had happened to any of them. The modest carpenter knew all about his illustrious twin, how many wars he had won for the tribe. He knew that whenever there was any problem, the Cojo entrusted him with the task of finding a solution. Everybody talked about the beads he had invented for the purpose of carrying out quick calculations, about his two-tiered folding ladder which made tree climbing so much easier (and to his chagrin, encouraged drunkenness, as it made it easier for people to tap their own wines from the palm trees). His other great invention was the hoe with holes in it to facilitate the separation of pebbles from earth, but it was undoubtedly his method of keeping the rogue elephants at bay which had earned him his unassailable position as the brains of the tribe. A man like him, the carpenter had surmised, is bound to be the best man to be tied to. Clearly if anybody can find the means of escaping the dire fate waiting for them, that man would be Midala the warrior.

Escape was naturally the first thing that Midala had thought of the moment he was captured, and he vowed to himself that somehow he would get out of this, but he was too shocked and angry to think of anything at the moment. As a military strategist, he never did anything impulsively, but collected all the pertinent facts first, weighed all the considerations, the risks involved and how to minimise them, and the advantages to be gained by the various courses open to him.

He was not happy with himself for allowing his plight to cloud his vision and for, thus far, not paying any attention to the misery of his brothers and sisters who had fought so valiantly and had nevertheless either been killed or captured. He never ceased to marvel at the bravery of the women generally, and of his own Rolena in particular. The cowards had felled her with their spear and stabbed her to death, and he had been unable to do anything for her, as he was himself fending off the assault of three attackers at the time. He knew why they killed her. It was clear to all that they had been ordered to seize as many captives alive, for a dead captive is worth nothing except to vultures and hyenas. Rolena had overcome two of her attackers, one armed with a gun, and killed them. They had been shamed by her valour, angry at being bested by a mere woman, and finally by the force of numbers and superior weapons, they were able to overcome her. There was no point in dwelling upon the fate of that most excellent of women. The warrior knew that death in a just war was not something to be deplored. It was a singular honour to die for the tribe, but he was a mere mortal, and the sight of the person he loved most on this earth lying on the ground covered in blood, lifeless, was unbearable, and it had quite unmanned him. He had thrown himself on her inert body and wept like a woman — which had made it possible for his enemies to overcome and capture him, thus earning a rebuke from the warrior in him. A husband reacts differently to a fighter. She had been a loving wife and mother. They had laughed together, had had a good life, he could always depend on her common sense, her loyalty to him and the tribe. It had been the dearest wish of both of them to grow old together and watch their children blossom into adulthood and give them grandchildren. A passionate and virile man, he had always laughed off suggestions by the elders of the tribe that he took more wives. Rolena was all the woman he wanted. The Spirits would surely welcome her in the Land Beyond and she will wait for him when his time came, and spend eternity together. He wished that it might be soon, but knew that it was his duty to stay alive, as he felt responsible for this brothers and sisters of the tribe. Alive he might be of some use to them. He could see his fellow tribesmen and women, shackled together, some like him and Bomo, others in threes or fours, some with wooden yokes locking their necks together, many of them bleeding as these implements of the devil tore into their skins and flesh. This was much more painful than being twinned, he imagined, for you could hardly turn round without hurting your neck as well as that of your fellow victims.

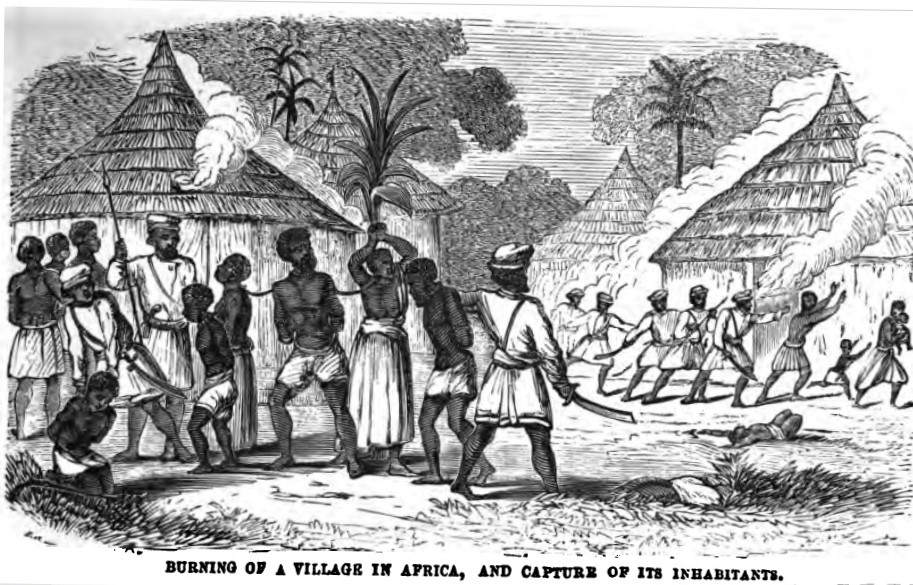

The massive Ibn Qalb, stroking his pot belly was in the forefront of the file, being carried by four Zanzibari youths in a palanquin. The English captain and his officers were in the back, laughing and enjoying the fruits of their treacherous victory, drinking masata which they had found a cache of. The burnt village was way behind them now, and it gave the vanquished warrior a sharp pain as he realised that he would never, in this life, see his beloved Mambocké where he had gone through all the stages of life from carefree childhood to lover and father.

There was an armed and mean-looking guard for every five or six groups. Some had spears and guns, which they used very liberally, prodding their helpless captives in the ribs with, often drawing blood, or hitting them in the back or in the legs, whilst others had scourges made of leather strips, which they playfully but menacingly twirled every now and then as a declaration of intent, occasionally putting their threats into action. These men were clearly not squeamish about the sight of blood. Midala was determined not to accept his fate, but he was not going to try anything desperate. For the moment he would keep his head down. He needed time to think clearly. The enemy was very powerful, and were the clear villains in this affair. He believed that the Spirits would never allow evil to prosper for long, nor the innocent and the virtuous to experience the bitter taste of defeat. You bear your tribulations with fortitude, and then as surely as rain follows thunder, your misfortune will vanish like ghosts at the first ray of sunrise.

The terrain was rocky and slippery as they were going down the cliffs towards the port, stumbling and falling and being bullied and beaten for this. To what distant land were they being taken? Would they see their loved ones again? Midala wondered whether he would see his son and two little girls again in this life. He had given them instructions, but who knows whether they had been able to do as he had instructed? They were so small and helpless, and the attack had been so sudden and had taken everybody by surprise. Had the Cojo done the right thing, the disaster that had befallen upon their nation would have been averted. Of that, he was more than ever convinced. The enemy was not invincible and that if only they had been given time to prepare…

By the look of it, half the population of the tribe, including half the children had been wiped out, and the other half captured. Ibn Qalb and Flyte-Camilton had not knowingly planned to murder little children. He would have liked to capture them, for they would have fetched a good price on the slave market. They could be trained to do any number of things. He had been told that in some countries, in the richer households, they liked having slave children perfumed and dressed up in fine clothes, serving the ladies and doing tricks for their amusement. The young girls were fed and clothed properly, and in all innocence, groomed to satisfy the sexual appetites of their masters and their friends. He wished that his daughters had been killed rather than experience such ignominy.

Photo Credit:

Wesleyan Juvenile Offering (public domain)

Photo Credit:

Wesleyan Juvenile Offering (public domain)

When he turned round to catch a last glimpse of the land of his birth, the fearless man was unable to stop his tears rolling down his cheeks. Bomo eyed him obliquely, and he too began weeping silently. The mute mulatto saw them and started laughing obscenely and this put an immediate stop to what the two men identified as self-indulgence.

As they went down the cliffs, they knew that one false step could mean a downward plunge into the abyss below. Midala had watched in alarm a pair of twins who had started at the front of the file, Wambane, a blacksmith and Biloko a medicine man, but they had gradually lost their lead. It was clear that Wambane was a very sick man, and could scarcely stand upright, let alone drag his tired body along. Biloko who was bruised all over and thoroughly exhausted, had to spend half of whatever energy he still had left, dragging his poor twin who had scarcely enough strength left in him to breathe, let alone lift his leaden legs. Blood was coming out of his wrist, his ankles and now his knees, bruised by repeated falls. Their guard had been deaf to Biloko’s entreaties to get his poor companion seen to, and had paid him with a vicious stab in the rib with a stick for his pains. Finally Biloko had no more strength left in his body and the two men crumbled into one heap and stayed there whilst the other captives had to produce the extra effort to avoid stepping on them. One guard rushed to the pair on the ground and started lashing out at them with a whip, calling them lazy sons of dogs. Another one arrived to lend him support, and they discovered that Wambane had died, whereupon the first guard asked his colleague what was to be done.

‘The Shaikh said not to waste time,’ the second guard said.

‘Let me go ask him.’

‘No, you son of a diseased warthog, there is only one thing to do, throw the bastard down the cliff and be done with you.’ They argued for a short while and finally agreed on this course of action, whereupon the first guard began to detach the dead man from his near dying twin.

‘What the fuck are you doing, you boil on the cunt of a diseased whore?’ The other tried to explain, whereupon the other guy spat on the ground.

‘There is no time for that, shiteater, just push the fuckers over the cliff and be done with you.’ The first guard looked incredulously at his colleague and then they burst out laughing. Just as they were about to carry out the task, Midala and Bomo drew level with them. Without a word, they flung themselves on the two guards and fell on them, overpowering them in the bargain. They would have been suffocated to death, but the furore drew the attention of other guards who rushed to their rescue. The collective wisdom of the guards decided on a whipping to death of the pair, and they immediately started acting upon their decision, taking turns, but Ibn Qalb who had been alerted by the noise, asked to be taken to the scene, and for a time he watched in amusement as the two men took their punishment, his beads in one hand and a bottle in the other. Finally by raising his hand he ordered this to stop. He stepped out of his palanquin and waddled towards the guards, every step he took, an obvious ordeal because of his great bulk. He examined the two captives who had dared to assault armed guards, nodding to himself. Suddenly he unfastened his dagger, which was obviously something he valued, as it was more a piece of jewellery than a weapon, with its silver handle encrusted with rubies and sapphires, and offered it to one of the guards, who made no effort to take it.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Ton Rulkens

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Ton Rulkens

‘Here, take it,’ he said in a kindly voice, ‘throw it over the cliff for me.’ Everybody looked at him as if he had lost his mind. Timidly the guard stretched out his hand, but not far enough to receive the princely object. Then in an angry booming voice, the boss bellowed, ‘You sons of syphilitic male whores, do you have any idea what these men will fetch on the slave market? What were you trying to do, ruin me? Take my dagger and throw it over the cliff… you may as well.’ The guards bent their heads down and looked at their feet. For a moment nobody said a word, and the captives held their breaths as well, and the faint music of the waves below were the only sounds they could hear. Suddenly Ibn Qalb screamed at the top of his voice.

‘Anybody ill-advised enough to damage my merchandise, will be tossed over the cliff, and I will take great pleasure in doing it myself. Now get a move on, we have no time to waste. Give those three men some water.’ Biloko was detached from his dead companion and the three men drank copious amounts of water, after which the surviving captive was tied to Midala, and at a stroke, the twins became triplets.

They reached the beach without any serious incident. A three-masted brig was at anchor, and it looked more like a ghost ship, with its paint almost all gone and weeds and barnacles covering the hulk. It was the Coimbra, a three hundred tonner, once a Portuguese pirate ship, now converted into a more lucrative slave transporter. Midala who had been told of the savagery of the waves in the open sea, did not believe that this cockpit would survive even a moderate storm. He knew that in a matter of days if not hours, they would be on board, heading for some foreign land where they would end their days in misery. With any luck, a storm might put an end to their misery before they reached their destination. A number of small crafts laden with people and goods were plying between the shore and the ship, no doubt fitting her for an imminent departure.

The captives were led into a massive shed, where they were given food and water. They saw a number of men waiting there, most of them white men or Arabs, and they watched anxiously whilst these men engaged in endless negotiations with Ibn Qalb and Flyte-Camilton. The men then began inspecting the captives, who were required to show their arms, their legs, and their teeth. Some were ordered to jump up in the air or do some similar feats, in order to impress upon prospective buyers how agile they were. Some were picked up and thrown on the ground in order to determine how fit they were. After a lot of haggling, the newcomers pointed at those captives they wanted to buy and small groups were led in different corners of the shed. Midala and Bomo were bought by the same man, who bought twenty more, including six women, but Biloko went to another buyer. The others in the party were likewise shared out.

Midala was intrigued by the sight of three people squatting round a stove, where a fire was blazing. The men might have been Zanzibaris or Swahilis from another part. They were smoking pipes, which they passed around to each other, and had some rods they were playing with. Midala and his batch were marched towards them, and the white man spoke to the men in a foreign language. A guard then pushed him unceremoniously towards the three men, and their intention became immediately clear to him, for it was a long tradition among the various tribes to brand their cattle with the marks of their owners, in order to stop cattle thieves operating. So, he told himself wryly, I have now been transformed from a human being into an ox. He knew that there was no way out of this, the enemy was too powerful. He therefore decided to accept being branded without a protest. He took a deep breath and braced himself. The physical pain was something he knew how to bear, it was the humiliation that he found difficult. What was unbearable was the thought that the children were also going to suffer this ordeal too. But he closed his eyes and heard the hissing noise as the hot metal was applied to his chest, and smelled burning flesh before he felt the pain. Every single captive, children included, was thus branded. Some howled in agony, many screamed and protested, but most bore their pain in defiant silence.

They spent the night in the shed, shackled together and then the people at either ends were tied to posts with metallic chains. All night long, the sailors and their helpers loaded the ship, for it was the captain’s aim to leave with the morning tide. Midala found it difficult to get any sleep. First, he was feverish and aching all over, the burn on his chest pulsated with pain, and he was unable to ward off the gloomy thoughts that preyed on his mind. The unceasing din did not help. When he did mercifully nod off, he was assailed by nightmares in which he saw his battered children lying in a great bloody pile, bleeding to death, and he, paralysed, unable to go near them to help. Then a couple of hours before daybreak, just when he had finally fallen asleep, some guards burst in, kicking the sleepers in the ribs, wickedly smacking their whips in the air, getting them to wake up. They were released from the post to which they had been tied, and pushed like cattle towards the small crafts which were waiting to take them aboard the Coimbra.

Midala decided to do as he was ordered. He was surprised to find that they had again paired him off with Bomo. After the fracas on the cliffs, anybody would have realised that they were a dangerous pair, but they thought that they had nothing to fear from them, that they had succeeded in enslaving their spirits. But both men knew instinctively that neither of them was going to just accept his fate without at least trying something daring and decisive.

Before being pressed on board, guards made sure that the chains and ropes round the captives were properly secured. As they clambered on board on precarious ladders, one pair of twins slipped and fell into the sea, and was immediately dragged to the bottom by the weight of their chains. Clearly they could not be saved, but the crew did not seem to have even noticed the fatal accident. Captives who tarried to have a look and commiserate, were roundly shoved and pushed, and threatened with whipping.

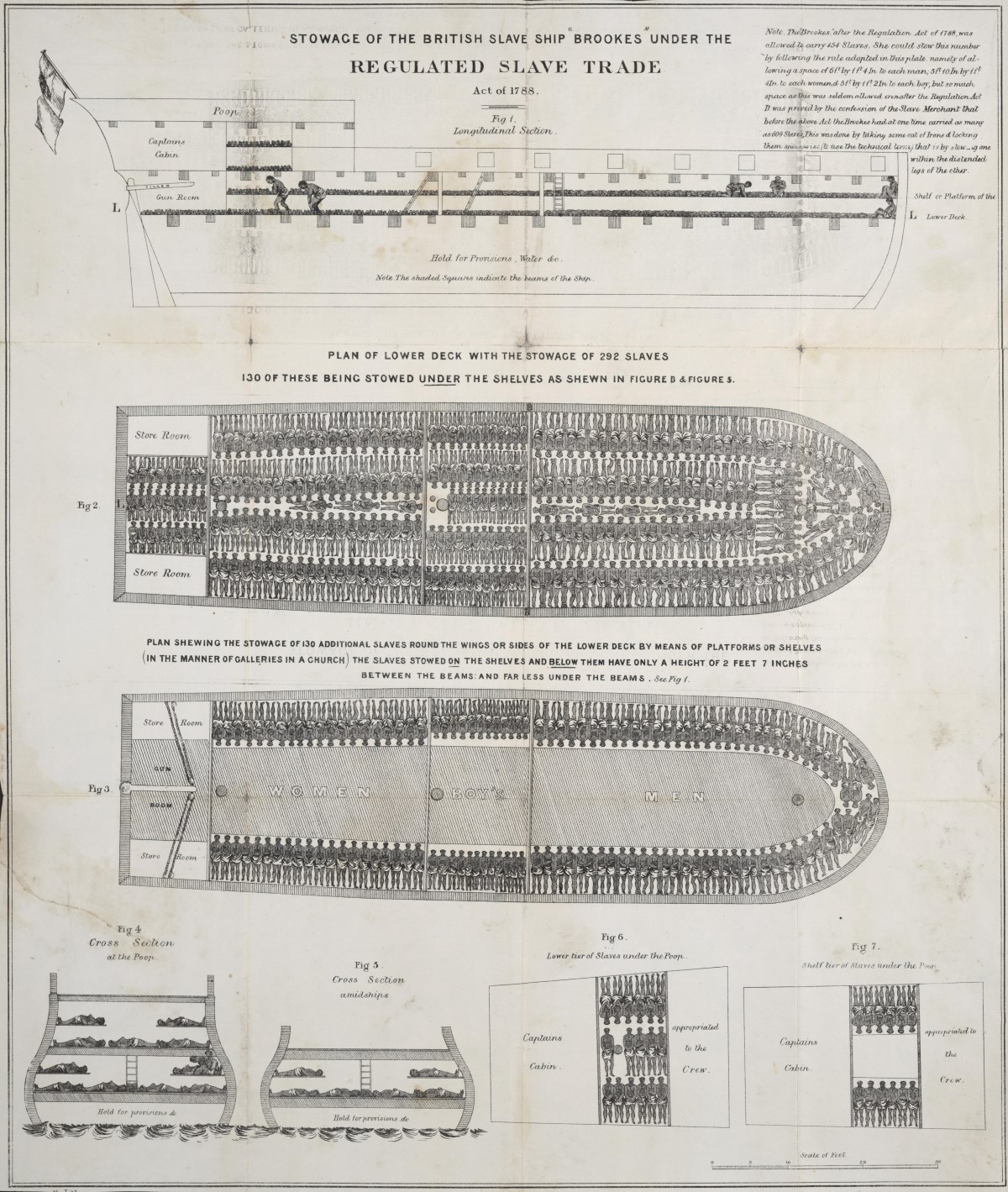

Once on board, they were led into specially designed holds. Midala’s heart sank as he saw the space where he knew he would be confined to for the duration of the trip, which might well be over a month. The platforms were made of rough wood, and the holds were no higher than a seven-year-old boy like his Abo. They were told to spread themselves out in very small areas, and he imagined that they looked no different from the ngaah left to dry in the sun, placed side by side, with hardly any free space between them. Already the stench was overwhelming; it was a mixture of sweat and urine, festering wounds and fear generated in the melee; as a warrior, Midala recognised the smell of fear. Above and below his own area, there were similar holds, possibly five or six, one on top of another, where more men, women and children were confined; he could hear their moans, screams and cries of despair and the frustration that he experienced at his inability to do anything for them was intense.

The ship had hardly sailed out of the harbour than seasickness set in. Everywhere in the hold, people began throwing up, and the stench in the confined space which was already quite nauseating was causing more vomiting. The moaning redoubled and soon it was the most desolate place on this earth. From the hold above where women and children were confined, the sounds of wailing and people being sick rent the air, and Midala wondered how anybody could survive this cacophony of despair any longer. He imagined that the Bad Place where bad people were condemned to spend eternity for their evil deeds on earth could not be worse. Mercifully he became so confused at that point that all this misery and despair seemed unreal.

Food was brought in later, and although they had been on a starvation diet for days and their stomachs were empty, no one had any appetite. Midala was surprised when the guards started screaming at them, but he knew that as they were commodities, it was in the interest of the captain and his associates to keep them in one piece. It was from this that his first idea sprouted. Afraid of the punishment that would be inflicted upon them, most of the prisoners, including Midala, made some effort to eat, but there were a handful among them who stood their grounds. The guards took them away and later he learnt that they had been whipped, and when they still refused, red hot iron rods were brought near their mouths until they gave up. He heard that one man choked to death as food was rammed down his throat and was thrown overboard. Also on the way back to the hold, two of them who were tied together, in a concerted action, threw themselves at the guards and overcoming them momentarily they sprang towards the railing and joyfully threw themselves in the boiling seas below. Midala naturally deplored the death of his fellow victims, but remembered thinking that with three less people, there was now going to be just that much more space for the rest of them.

About a week after they had left Inhambane, Bomo, who was familiar with the language of talking drums, noticed that two adjacent planks on which they were lying were made of different wood, and were not of the same thickness, and began tapping a message with a nail held between his two smallest fingers and a stick between his thumb and index finger: ‘I am Bomo the carpenter, and I greet you all.’ At the far end of the hold above, Chissane who thought he was dying heard this. He too knew drum language, and his neighbours were surprised when the young man mysteriously perked. Most people had not even heard the coded taps from Bomo, and were surprised. Chissane made a superhuman effort to raise his body just a little bit, and his companions, feeling sorry for the dying man, were willing to give up some of their already limited space for him and squeezed themselves more tightly. Weakly Chissane began tapping on the floor. Bomo smiled as he understood the response: I am Chissane and I want to die. Bomo whispered this intelligence to Midala, who immediately shook us head. No, tell him not to lose hope, tell him that we must live in order to fight for everybody’s freedom, tell him that we will find the way to regain our liberty. Bomo nodded, and tapped his message, adding that Midala himself had told him to convey this message. It required little effort to communicate with the captives in the hold above, and in the great tradition of bush telegraphy, the message was relayed to the whole ship. Soon everybody, having heard of Midala’s presence among them, began to cheer up and murmur among themselves. Ask if anybody has any idea of where we are going, Midala told Bomo, and the carpenter tapped away. The answer came back almost immediately after: The big island, Madagascar. Midala did not know that name, but he had heard of the big island. He wondered what was there, why they were being taken there.

On the next day, the ship began to roll rather dangerously, and this grew more intense by the minute. It was clear that a storm was brewing. The helpless captives were propelled one way and then the other, some failing to avoid knocking their heads against the hull, and a chorus of agonised screams tore the air. Outside fierce winds were howling, and there was not one man, woman or child who did not think that their last hour had come. Even the hardened sailors who must have been used to the vagaries of the high seas seemed to fear the worse. The winds roared furiously and the waves tossed the ship up like a mean cat tosses the mouse. Inside, more people were getting their skulls and bones cracked as they were flung against the sides of the ship. Many, weighed down by the heavy chains were unable to pick themselves up and not a few got smothered to death. This went on for hours and when the storm had finally abated, most people looked at each other surprised that they had survived yet another ordeal. All night long there was wailing and mourning for the dead, and in the morning the guards came, detached the dead from the living, took them on the deck and unceremoniously threw them overboard to the sharks.

As people were shackled and there was no one to free them whenever they needed to answer the call of nature, they all had to bear the ignominy of emptying their bowels and bladder on the spot. By now everybody had lost what little clothing they had when they came on board. When you are covered in your own excrement, it is the most difficult thing in the world to maintain your dignity. The humiliation brought tears to the eyes of all, and a big lump to their throats. They felt diminished as human beings and had to fight hard in order to stop the animal nature in all human beings from gaining the upper hand and rise like a bilious sap up their heads and poison their brains.

Every other day, groups of captives were led up the deck, in an attempt to keep them fit and alive. It was feared that if they died or were in a bad shape when they landed, the size of the profit for the captain and his partners would shrink. The exercise usually comprised of getting the men to jump up and down randomly and dance, to the sound of tom toms provided under duress by their fellow captives. The men badly needed the exercise after having endured almost forty eight hours of inertia in an area where they could hardly move, but it was obvious to them that jumping up and down on the deck with no clothes on was a singularly degrading sight, especially as the guards and sailors would gather around them and cackle obscenely. Often they refused to submit themselves to this, and were whipped for insubordination. It was this that gave flesh to Midala’s idea.

They had gathered enough information by means of their improvised telegraphy, and they agreed that if they were to take over the ship, this would have to be done during the exercise break, when a batch of over fifty captives would have the freedom to roam the deck for about an hour, albeit under armed guard. Furthermore, the exact whereabouts of captain, crew and guards were now known to them, and this enabled them to work out a plan. When everything was ready, they would risk everything on a specified day. For the plan to work, the element of surprise was vital, but as all information transmitted were only understood by the captives, with captain and crew unaware of the signals being exchanged, there was next to no chance of their plan being known by the enemy. A date had been set, and Midala and Bomo had assigned a role to all the men and women who had enthusiastically volunteered to take part in the action. The guards and crew had not failed to notice a sudden change in the attitude of the captives who did not look forlorn and consumed by despair any more.

On the morning of the action, a dead woman was thrown overboard, and many volunteers saw this as a bad omen. Midala was shocked to find that not only were there many more guards than usual, but they were all armed with guns. It was more usual for them to have a stick or a whip. Midala suspected that luck was against them, but orders had been given. He suspected that they might have been betrayed, that someone, expecting some reward had gone and spilled the beans, and Flyte-Camilton was ready for them. He looked at Bomo who pursed his lips. There was only one thing to do, tell his followers to abort. He took a step forward and was about to open his mouth, when Bomo brushed past him and in a loud and clear voice shouted at the top of his voice: Friends, we are betrayed, do nothing. Immediately three armed guards flung themselves at him, overpowered him and led him away towards the captain who had been watching the development. He ordered that Bomo be whipped to death, unless he revealed the names of all his accomplices. As Midala knew, Bomo said not one word, and was tied to a mast and mercilessly whipped. He bled, fainted, was revived, was whipped some more, until he finally passed away. The captain talked with his officers and they decided that after having made an example of one rebel, there was no risk of further disturbance, although he did not doubt that there were many others involved. In order not to compromise the size of his profit, no further action needed to be taken.

Next Bolimbo, a fishnet maker threw himself to the sharks, and Midala soon found out why. The man had learnt by the drum telegraphy what Bomo and Midala had instigated, and as his wife who was in the upper hold was seriously ill, he had thought that if he told the officers what he knew, they would reward him by giving her some white man’s medicine, but the medicine had not worked and she had died. The shame of betraying his own people for nothing was too much for the heart-broken man. It was the wretched woman who had been thrown overboard in the morning. Strangely, no one had asked Bolimbo how he had found out about the planned action.

Everyday someone died and was thrown to the sharks. By now the spirits of every single captive seemed to have been broken. No one had accepted the fate awaiting them, but they did not have the strength to hope.

Photo Credit:

The Slave Ship, by JMW Turner (1840, public domain)

Photo Credit:

The Slave Ship, by JMW Turner (1840, public domain)