They had all told her that for an unmarried mother, life in the Highlands was going to be unbearable, and urged her to go to Canada with John Robert. It was a new country, and people who went there were would not have the leisure to be judgmental. If she was after a normal life, it was her only chance. The one impediment was Rob Rob. She was sure that he would come back for her, and did not want to leave him heart-broken when he found that the family had gone God knows where. However it soon became clear to her that Hugh, Martha and Grand Mam were not planning to go anywhere. They were born Highlanders and wanted to die within sights of their glens and lochs. Selfishly Catriona thought, when Rob Rob came looking for her, Da would be able to tell him where she was, and he would surely come find her. Til a’ the seas gang dry! She was as sure of that as she was, of John Robert being the spitting image of Rob Rob and the prettiest baby in the whole world. Yes, she would go join her brother in Canada. With her, having once taken the decision, she did not once feel or express any regret. It was like with Rob Rob, she had decided that she would give herself to him, and she did and she never regretted the outcome.

Hugh, Martha, and Grand Mam who had urged her to go, found the thought that they would never see her again almost unbearable, but they put on a brave face, and kept saying that they would manage. They had everything they needed for a comfortable old age, they swore. In material terms that was true. It was the fact that they felt this had to be said so often, which made Kitty uneasy. She would love them forever, they had been caring and loving parents. Distance would make no difference to that love. She knew that apart from the shame of having been a wayward daughter, who, in the eyes of the world, had brought shame on the family, she had been dutiful and loving too, so there was no regret there. In any case she did not think it shameful to give yourself to the person you love. If she could put the clock back, even in the knowledge that she would never see Rob Rob again, she would not hesitate doing the same thing all over again, for at least now she would have a piece of him for keeps.

John Robert had brought a lot of happiness to the lives of the family. Grand Mam who had been gradually sliding into apathy, and had said that her time was nigh, suddenly grew a new skin, her eyes regaining their old sparkle, but even she insisted that for the sake of the little mite, there was no better option than to go away. You will both be happier there, the family said. What is happiness? Kitty asked herself? Put on one pan of the scales the happiness of having your loved ones around, minus the unhappiness of poverty and the certainty that there was no future for them, and on the other pan the knowledge that the loved ones had every chance of a good life minus the unhappiness of knowing that they would never see each other again. Which way would the scales swing? Difficult to say. Probably about an equal balance. But The Manufacturers’ Committee was offering funds and Kitty and baby John were going.

The whole family set out from Helmsdale to Cromarty by boat. The parting in Cromarty was tearful, and Kitty who had promised herself that she would maintain a cheerful front was unable to stop the flow of tears, but the moment she was on board the Milton, her eyes immediately dried up, but only for a short while. When she was led to the multi-storied hold where she was going to spend about six weeks, seeing its desolate nature and the space allowed for each passenger, her eyes became once more heavy with tears, but she managed to hold them inside. Looking at the number of women and children she was going to share this space with, she made a quick calculation and arrived at the conclusion that there was room for only half the people to lie down at any given time, whilst the rest would have to sit up huddled together like spoons in a box. The height of the compartment was such that you had to move with bent legs, your head down, if you did not want to knock it against the ceiling. She hoped the women would make allowance for the babies and children and squeeze themselves a little bit more, and grudgingly they did.

Once all the passengers had embarked and the tide was favourable, the Milton weighed anchor and slowly started gliding away in a northerly direction, with a chorus of sea gulls squawking to bid them God speed, as they rose and fell with the rocking billows. Not to be outdone, a trio of stormy petrels skimming the surface of the water happily showed them the way. The winds were favourable, and in a matter of hours they were once more at the level of Helmsdale. John O’Groats came next, and then the ship changed into a westerly course, heading for the Atlantic, when a strong wind made the ship rock, triggering a general onslaught of vomiting.

Kitty and John were sharing a space no bigger than the floor of their hut in Strathnaver with twenty other women and children. A foul smell of vomit filled the atmosphere, but she herself was not seasick. It was explained to them that in order to sleep, they had to agree between themselves and take turns. There would be bells to indicate the changeover. The crying of the little ones was almost continuous, except for short periods in the middle of the night. It was like a relay race, the moment one lot stopped, like they had passed the baton to a fresh lot, another started. John Robert was quite a handful, but Kitty drew much comfort from holding him tight and cuddling him. The toilet facilities amounted to no more than a couple of buckets behind a torn curtain in a corner of the hold, and the constant rolling of the ship caused many a spill, which did nothing to improve the already foul stench. She was able to lie down for a couple of hours, after which her neighbour woke her up, apologising profusely, pointing out that it was her turn, but she took John in her arms and sat up, and mercifully he continued to sleep.

In the morning they were allowed two hours on deck, in batches, to stretch their legs and take in some fresh air, and Kitty watched in wonder the blue waves rolling and crashing against the bulwark of the Milton. The food, consisting of dried biscuits and pickled herrings, was adequate but many passengers could not keep it in, resulting in more unpleasant stench. That was going to be the pattern for another five weeks, she thought gloomily.

She had not counted on a deterioration of the weather. Fierce winds made the ship roll dangerously, and people screamed as they prayed for their lives. Dante’s Inferno, Kitty imagined. As if that was not bad enough, the winds swelled into a real storm. People got thrown all over the place, and one woman died of a cracked skull. At the end of the storm, another four passengers had met a similar fate in other holds. She, who had always been full of compassion, was disappointed and shocked when she found that as people died and were buried at sea, instead of mourning for them, most, if not all her fellow passengers, herself included, saw this as a gain in space for themselves. Recognising her selfishness, her self-worth suffered a serious jolt. That’s not who I am, she kept telling herself. I’m only thinking of the baby, she explained to herself.

After five weeks, when Kitty and everybody else had reached the end of their tether and some people started talking of throwing themselves overboard for a merciful end to their suffering, the Milton found itself approaching the shores of Newfoundland. This is the place where John had not met his untimely death, she reflected wryly. The brown rugged, ragged and desolate coast was one of the most welcome sights she had ever seen, and the land breeze was most welcome too. What cheered the weary travellers more than anything, was the number of birds gathering round the ship, doing acrobatics in the air, swooping down with abandon, merrily chirping or squawking. Then, re-energised, they would soar up again, only to repeat this enchanting choreography. There were ducks and geese, seagulls and cormorants, swallows and albatrosses, and they instilled in the breast of the people coming into this new unknown world some badly needed optimism.

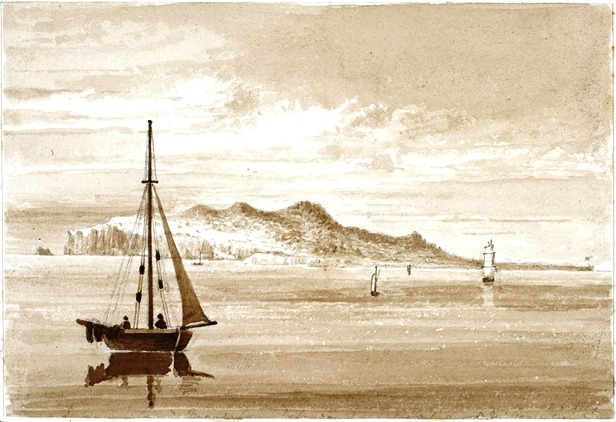

Photo Credit:

John Crawford Young, 1825-27 (public domain)

Photo Credit:

John Crawford Young, 1825-27 (public domain)

It did not take them long to reach the Gulf of St Lawrence. Kitty gaped at the ninety mile mouth of that waterway in wonder. It looked more like the open sea than the mouth of a river. After a short while, the outlines of the coast on the southern side of the river begin to appear more distinctly.

Kitty watches in rapt admiration the clouds rolling along in colourful billows as they catch the sunbeam, giving it a rosy hue. They seem to be playing hide and seek: now you see them, now they have disappeared. It is as if they are alive and have a mind of their own. Soon Green Island emerges in a distant mist, and as the Milton approaches it, the shores with houses and farms become visible, most with tin roofs brazenly reflecting the sunlight.

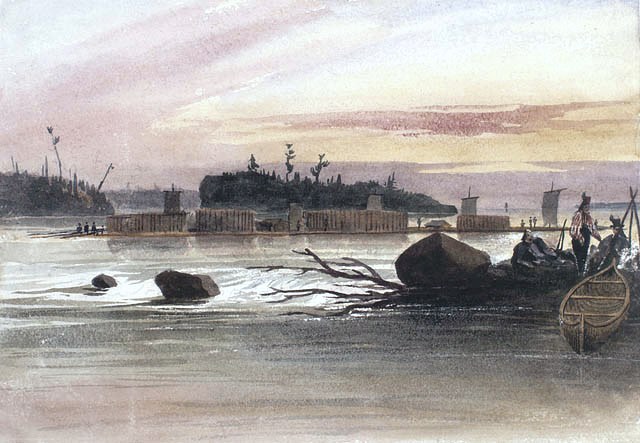

As the ship approaches Gros Isle, a rocky island with attractive groves of beeches, birch, ash and fir, two ships with yellow flags are sighted, signalling an outbreak of cholera. This means some form of quarantine was being enforced. She is weary of the interminable voyage, and is impatient to be on terra firma, but for John Robert’s sake, she welcomes the tedious formalities. The boy has had a bad crossing, and is lucky to make it so far, and she does not want him to be exposed to a fatal illness so near the destination. Three whole days are spent in quarantine, where passengers are checked and vetted.

Photo Credit:

Philip John Bainbridge 1840 (public domain)

Photo Credit:

Philip John Bainbridge 1840 (public domain)

John Robert had been all right when they were finally given the all clear and they set forth towards Quebec, but mother and child were admiring the Montmorenci falls when the child started fidgeting and then began screaming. It was obvious that he was in great pain, and no manner of cajoling and cuddling would make him stop. She was greatly alarmed when she found that he had become so hot that it was like holding a loaf just taken out of the oven. Next he began throwing up and had the runs. She began panicking and an officer took mother and child to the ship doctor’s, although as an unwritten rule only first class passengers benefited from his immediate services, often leaving passengers from the other classes to die before they could be seen. He said that it was not unusual for a little child to have high temperatures, believed that the fever would go down of its own after making him swallow a tablet, and urged her not to worry. However, the temperature showed no signs of abating, and the vomiting got worse, as did the runs. She screamed that she needed the doctor, but confined in the hold with scarcely any room to move, nobody heard her and nothing could be done. John Robert passed away in the night. As did three adults and two more children. The captain panicked and ordered that the dead be buried at sea without delay, as cholera was known to spread like wild fire. People were quick to point out that the quarantine which was supposed to be a preventative measure, was in fact what had exposed them to the catastrophe. Prior to the forced landing at Gros Isle, there was not a single case of cholera on board. But what was the point of finger-pointing now?

Kitty was disconsolate and thought that she was going to lose her mind. She too got a high temperature and became delirious, screaming that she wanted to go back home, when she would have her baby back. People kept away from her, fearing that she would contaminate them. She did not know how she survived.

When her high temperature subsided, she had neither the inclination nor the strength to go on deck to catch a glimpse of Quebec, a majestic city built on a magnificent rock. Her neighbour, impressed by the sights, kept describing the sights in lyrical terms, with an insensitivity bordering on callousness. What did it matter to her that there was a magnificent fortress overlooking the river on Cape Diamond? Why did she not just shut up and let her die?

That night she slept fitfully, waking up in a panic every now and again, clasping emptiness instead of her little baby.

She had no inclination to watch the varied landscape on either banks when the river narrowed and when the scenery became more varied and picturesque as the Milton went further up river. The number of orchards lining the shores, bending down with rich harvests of apples and plums was astounding. Were there enough mouths in the world to gobble them all up?

The travel-weary multitudes who had braved winds and tempests to come look for a more comfortable life in unknown territory were greatly heartened by the signs indicating that poverty had left these shores forever. The soil seemed more fertile, making for a lush green vegetation. This was what had obviously attracted settlers and as a result instead of the rudimentary log-houses further down the river, there were now tastily built houses with windows and steps, mostly painted white or pale-green.

Kitty had lost all concept of time when they reached Port Hope, where John had said that he would be waiting for them. She had no idea how long it was since her baby had passed away. Very few passengers got off, and Kitty was relieved to have reached her destination. John was waiting, and brother and sister held each other, crying for a number of unsaid reasons: their much loved parents who they will never see again, her lost little boy, the glens and lochs of the land that they had left behind and which neither will never see again, her lost love, their childhood. John did not immediately register the absence of the little boy, not having known him, but she tearfully told him the story of his needless death through bad planning. John had come in a horse-drawn carriage which his employer had lent him to pick up his sister. It was a two-hour ride to Oxenham, on the shores of the Rice Lake.