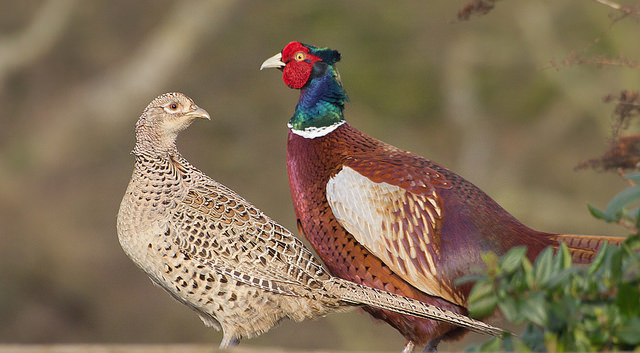

Katrina had cycled extensively in the Highlands and had spent three days in Ullapool. The town was charming enough but not what she would have called riveting, and feeling a bit blasée she had thought of giving a miss to the usual tourist sites. She had checked in at the Eilean Doran Guest House, and had been quite content to take things easy, and catch up with her reading and watching television. One of the articles she had read only last night, was Donald Robertson’s paper on the Godwit. He had something of a reputation in ornithological circles. She had obviously read most of his other writings and had been impressed by the clarity of his exposition, his lucid and intelligent conjectures. She remembered how disappointed she had been when at the Smithsonian, she was told that she had missed meeting a man whose work she admired so much, by just a week.

She was fetching her bike from the garage, aiming to go south, although as yet she had not decided where, when suddenly the Canadian cyclist appeared at the gate, pushing his bike which he had just dismounted. He took a deep breath and made for Katrina.

‘Ex-ex-cuse me, is this the the the… Eilean Doran?’ They both laughed as they caught sight of the massive billboard with the name EILEAN DORAN writ large, under which they were. On a sudden impulse and the vaguest hunch, Katrina, knowing that he was Canadian asked, ‘Excuse me, are you by any chance Donald Robertson?’ He dropped his bicycle which went crashing to the ground, and he made no attempt to pick it up. He stared at her, dumbstruck, craning his neck in her direction, opening his eyes wide. Any onlooker might have taken him for a half-wit.

‘D-d-d-d-doctor C-c-c-crialese?’

As Don was still thunderstruck, Katrina decided to put him out of his misery.

‘Only last night I was reading your paper on the Godwit. Tremendous!’ Don took a deep breath, and reminded himself of his many strategies to speak without stammering.

‘Oowhen Aye oowas at zthe Sim-mithsonian, Aye heard sso mmuch aab-out you… always oowanted t-to emmeet you.’ In his estimate his strategy had worked, and that alone gave a big boost to his confidence, which facilitated his delivery. Katrina found his speech pattern strange, but did not immediately recognise it as an allotropy of the stammer. After talking shop with the man whose work she had always admired, and having learnt that they were going to be colleagues at Aberdeen, she took the decision to extend her stay in Ullapool.

They had tea and scones in the dining room of the Eilean Donan, and in the afternoon, they went round Ullapool on their bicycles. That evening they ate lobster and drank Viognier.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Roy Lathwell

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Roy Lathwell

On the next day, they cycled the twelve miles to Braemore to visit Corrieshalloch and the suspension bridge. They left their cycles in the car park and walked the narrow path to where the mile long gorge began. Neither of them, seasoned travellers though they were had seen anything so breathtaking — or so they claimed. The walls were almost vertical, and the river Droma flowing over a number of waterfalls below was a stunning sight. It was whilst walking on the suspension bridge that Donald, who had been thinking of nothing else since the start of the trip, managed to grab hold of Katrina’s hand. She reacted with mild hostility to that, as she did not like the idea of the male offering succour to a damsel in distress, but almost immediately after she identified this for what it was, a tentative attempt at establishing physical contact, and she smiled. Besides it felt nice. She was a sensual woman. It was more than the warmth of his hand that appealed to her, everything about the contact was pleasant. The pressure on her hand was firm without being aggressive or possessive, and when inevitably, shortly afterwards he began to gently play with her fingers, she closed her eyes and enjoyed the moment. They found it difficult to part with each other that night.

On the next day, on Ullapool Hill, they walked among the pine trees hand in hand, for long periods saying nothing. When they saw the place where as part of a project, some school kids had planted trees mirroring the vegetation that their ancestors migrating to Nova Scotia would have first seen on landing in Pictou in the late seventeen seventies, Don became a tad thoughtful.

‘One of my g-great great…’ he said, making a flowing gesture with his hands to indicate he wasn’t sure how many greats he should say, ‘grandfathers sailed on the Hector from Loch Broom.’

‘One of my ancestors was a slave from Mozambique,’ said Katrina.

Two young people in the prime of life, at the pinnacle of their profession, with the world at their feet, reflected on the long voyage that took their ancestors, from places that most people had never even heard of, to that spot in Ullapool. Each was thinking of their ancestry: the destitute Indian family who had mislaid their father, the near starving Highlanders forced out of their land, the proud slave ancestor who had refused to accept bondage, the original Steve McQueen, for whom no jail was unbreakable, the gipsy woman transported for stealing a chicken to feed her younger siblings, the Ojibwa man who knew about geometry, the labourers who tried to stand for their rights, the great great great grandmother who had had to submit to rape and violence before marrying the eminent scientist who had sailed up and down the Essequibo. The hero of the battle of Sind. The simple peasant grandfather who was forced to carry out the orders of the Nazis at Babi Yar and then ended up a hero at the Odessa Catacombs. So many others who must have had similar histories but about which they knew next to nothing.

It was at this spot that the pair exchanged their first kiss. The sun was hidden by a dark cloud, and a cool breeze was trying to subvert summer. Don had a hand over Katrina’s shoulder, and he squeezed it gently, which made her lean over helpfully, making the kiss the next obvious and inevitable move.

‘I’ve I’ve b-b-been looking for you all my life,’ said Don almost without stammering, ‘and f-f-fell in love with you in the Hamish. D-d-de you remember our paths c-c-rossed there?’ Katrina nodded, laughing at the memory. Hope he doesn’t come and sit at my table…

Although no words were said to that effect, at that moment, they both knew that they would spend the rest of their lives together.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Ian

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Ian

After the Highlands, they still had a few weeks before Jolyon came back from Australia, and they were free to travel south of the border. They found railway travel was not cheap. They visited Bedford and Dunstable. Katrina could not decide whether she truly remembered Dunstable Downs with its gliders, or if they were false memories based on photographs and stories heard.

When they finally arrived in Aberdeen, they found accommodation in Beach Boulevard, from which they could catch a glimpse of the Esplanade. They decided against living together, and took separate flats in a newly built apartment block, on the same floor, opposite each other. Conveniently, Ananda Garg who was going to be part of their team was able to get a flat in the same building, but on a lower floor. They all settled down and started working on their exciting new project with the enthusiasm of the dedicated scientists that they were. They worked hard and during weekends, Don and Katrina either went hill-walking or cycling. Sometimes they went camping on the Cairngorms. Ananda’s wife Roopa who was a television producer in Delhi had not joined her husband, but planned to come visit him twice a year. On some occasions he joined them, but he always seemed to be either on the phone to Roopa or expecting a call from her. As a rule the three of them had one meal a week together at home, during the weekend, usually Sunday late lunch, as they called it. Late, because it started late, giving everybody time for a lie-in, and it spilled until late afternoon, making dinner unnecessary.

Don had no culinary talent whatsoever. Katrina was good at following recipes (Gina had dictated a good few to her), and Ananda used to say that if he had not become a zoologist, he would surely have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a Chef. He was indeed an excellent cook, if a bit on the fastidious side. Indian cuisine, he explained, was designed to keep our virtuous Indian girls virgins until they married, by tying them to the kitchen in order to keep their minds off sex, so that the more time-consuming and complicated the method of cooking was, the more popular it was with the anxious parents. As a consequence, with all the time in the world available, he explained, elaborate recipes evolved through fine tuning, which is why, Indian cuisine is the best in the world. Don’t take my word for it, he said, that’’s what Einstein said. To anybody unconvinced by his oratory, he would give a discourse on Indian spices. Not only did we give all its known spices to the world, from aniseed to Zaffran, we also have the honour of not including horse radish in our cannon! Ananda loved an audience when he was cooking, so he could display his artistry, and at the same time, regale it with tales of famous bhandaris and their oeuvres.

The Indian ornithologist was an aficionado of pasta, and Katrina almost always cooked fusilli or macaroni for the boys when they met at her place. He said spaghetti reminded him of worms. Alternately they would invade Ananda’s kitchen and help the Bengali expert make kormas, biryanis, koftas and what not, peeling onions or potatoes, squeezing lemons, or mincing lamb (he did not eat beef). He did everything with a certain panache, holding the handle of the frying pan above the flame and twirling it round with studied insouciance. He always claimed that the end product was not quite what he had hoped for, but he now knew how to make it better next time.

He was a lover of good whisky, and said that this was why he had been so keen to come to the land which produced the finest single malt ever distilled this side of Svarga, the Hindu paradise. Don and Katrina were not averse to a tot or three of Glenfidditch either. Interestingly the Canadian never stammered on Sundays. Ananda would regale them with stories of his Saurkundi Pass Trek and the birds he saw and photographed there. Himalayan Bulbuls and Himalayan Griffons, Bonelli eagles, Hume’s warblers, pink-browed rosefinches, among hundreds of others. He had a fund of stories about India, the Kolkata of his birth and his adopted city of Delhi. He loved telling old Indian folk tales, and his guests loved listening to them. One day Don, having imbibed rather more single malt than usual, suddenly declared that he knew the best Indian tale ever, and bet that Ananda did not know it.

It was a story an ancestor used to tell the children, and was like an heirloom, being passed from generation to generation. Surprisingly he was told it by his rather austere father.

‘There was a man who p-p-possessed a unique well,’ he began, ‘and for some reason, he d-d-decided to sell it.’

‘Oh, I know,’ interrupted Ananda, ‘it is a Birbal story, go on.’

‘I also know a story about a man who had a gold well—’ Katrina said, ‘my grandma Gina was told it by… eh, my Indian ancestor. Sorry, go on, Don.’

‘Yes, it was a gold well… anyway… a man from Bihar b-bought it, paid his money and the v-vendor seemed happy enough.’

‘A man from Bihar? That was in my story too, how extraordinary.’

‘Birbal never told stories about men from Bihar!’ said Ananda with finality, ‘so it cannot be the story I know.’

‘In my story,’ Katrina went on, ‘the seller came back and—’

‘In m-mine too… to c-c-claim the gold…’

‘In Birbal’s too,’ admitted the expert.

It turned out that Don’s version was identical to the one Katrina knew, and this left the lovers perplexed for a while. Surprisingly the idea that it might have emanated from a common source did not seriously attach itself to either of them. Admittedly they each had Indian ancestors, and from Bihar too. Don never knew the circumstances in which his great great… however many… grandmother Devi found herself in Demerara, as his parents and grandparents did not remember or did not know. The mist of time had thickened into a pea-souper. Katrina only knew what Gina had told her, and many of the facts had got filtered away as one generation retold the tale to the next. She knew that there was an ancestor called Shanti who had mislaid her husband whilst catching the boat to Mauritius; that was what Prakash had told Gina.

One day, Katrina asked Don why he had decided to go to Ullapool. Because his great… grandmother Devi had once said that although she and her father had migrated from the Sundarbans, they had originally come from a place called Allapur in Bihar.

‘That’s uncanny, Gina also said that my soldier grandfather had ancestors who came from there, I thought Ullapool and Allapur seemed quite similar, so… call me stupid—’

‘Could it be,’ wondered Don aloud, ‘n-n-n-o, how c-c-ccan it be? This is real life, not Mills and Boone.’

Ida, who exchanged emails with her brother almost daily, had often said that she would seize the first opportunity to come visit them in Aberdeen. I am so keen to see for myself this paragon who seems to have ill-advisedly fallen for your hidden charms — hidden to me at any rate, she had written. Don was overjoyed when she phoned at three one morning to announce that she had booked herself on a flight to Glasgow. And good soul, he had rushed out and knocked on Katrina’s door, not wanting to keep that exciting news to himself.

Ida had rented a car and driven to Aberdeen.

‘I don’t believe this,’ she exclaimed the moment Katrina and Don opened the door to her, ‘you look more like his sister than I do.’ She elaborated.

‘I mean you do not have the same features, but I am talking about the overall picture, the bearing… know what I mean?’

‘All ornithologists all look alike.’

‘No, all Indians look alike.’

‘One of our ancestors must have misbehaved,’ Ida said.

‘Definitely an Indian one,’ said Ananda merrily, ‘if you only knew what goes on in those gaons.’

It seemed that Don had urged Ida to come over in time for the celebration of the first anniversary of their first meeting in Ullapool, although why this had taken such an overblown importance, Katrina could not fathom out. Unbeknownst to her, Don had planned to pop the question, and had wanted to share his happiness with his sister.

The Italian woman planned an Italian meal for themselves and Ananda on that Saturday. She was useless without recipes but with her scientific habit of following clear instructions, she did not feel daunted by the task. Usually when she set her mind to it, she made quite acceptable — Don said excellent — dishes. Also she prided herself on always carrying out her tasks in the most rational manner. She told the others that she wanted no help from them at all, preferring, as always, to work by herself as she found it easier to concentrate. She gave Ida the choice of sitting in the kitchen watching her cook or watching the Old Firm match with the boys on STV. Ananda was a great fan, and welcomed the opportunity of showing off his reading of the game but Don and Ida hardly understood the rules. Still they were happy to sit in front of the telly with cans of beer for a change. Don had got a few bottles of San Miguel in the fridge. Ananda agreed that whisky and football were incompatible.

She had planned everything perfectly, and everything was ready exactly at the end of the game. They ate heartily, drank Chianti, and ate Ras Malai which Ananda had brought for dessert. After the meal they played Upword, a multi-storied scrabble game for a bit, and Ananda kept making words which the others had never heard of, swearing that they were perfectly valid Indian spellings of words they knew differently. It was good fun.

When Ananda said he was going, Don said to hang on for a bit, he had something to give Katrina, and he wanted him to see it too. Typical of him, instead of producing it, he had to say a few words about it first.

‘It is s-s-something special… even unique I would say. You m-m-might say it’s incomplete, but it’s special just b-b-because of its… incompleteness. It is my most prized possession, I have it in my personal luggage w-w-whenever I travel… Ida knows what I am talking about. She was so jealous when Mum gave it to me instead of her.’

‘Not true,’ said Ida weakly.

‘M-m-mum ss-specifically said I should give it to my wi-wife… she…’

He stopped suddenly at that point, possibly overcome by emotion, and started blinking at a furious rate — something he had more or less stopped doing. Katrina put her hand on his arm and gently squeezed it.

‘I wished I knew its full history,’ he continued, ‘all I know is that it b-b-belonged to our Indian ancestor… my great great g-g-g-reat grandmother Verity—’

‘Her real name was Devi,’ corrected Ida, ‘They forced her to change it to Verity.’

‘I n-n-never-knew that,’ said Don.

‘You were never interested in the notes and diaries of the ancestors,’ she challenged.

‘Anyway… at her death it was given to my… great great grandfather… also called Donald… and… eh… to cut a long story short, m-m-mother gave it to me, and said I should give it to my wife… I want to give it to Katrina… as an anniversary present… eh…’ He fumbled in his pocket for a bit, became alarmed when he could not find it.

‘I c-c-can swear I p-p-p-ut it in my pocket when I left the f-f-f-f-flat…’ He stormed out in a panic.

‘Trust my dear brother,’ said Ida laughing. Don stormed out of the room.

Katrina and Ananda exchanged smiles, and waited for him to come back. He did almost immediately.

‘As I said, I n-n-n-knew I had it in my p-pocket, it was there all the time,’ and he produced a small plastic pill box and gave it to Katrina. She took it, studied the box, not rushing to open it.

‘C-c-come on, open it,’ urged Don.

Katrina shook her head. Her eyes were filled with unshed tears and she felt a big lump in her throat. ‘No,’ she said finally, ‘I know what it is.’

‘I can’t bear the suspense,’ said Ananda with pretend impatience.

‘You said that it’s a family heirloom, from your Indian great great great great grandmother. Let me see, it’s a small item, and you said you always have it with you… funny, but I too have something I always travel with… eh… also something which comes from an Indian ancestor.’

She could not continue, so great was the emotion. But she took a deep breath, smiled apologetically and made an effort to pull herself together.

‘That is such a coincidence… that the two of us should have… no, it’s too far-fetched.’

‘What’s so far-fetched?’ Ananda wanted to know.

‘Everything! First, we meet in the Trossachs, and have the same bikes… we are both working on bird migration, we are both joining Jolyon’s team… we both did a stint at the Smithsonian… it’s never-ending… uncanny.’

‘W-what is it that you always t-t-t-travel with?’ asked Don.

‘I’ll show you,’ said Katrina. Her expression had changed suddenly. It was as if she was scared of something, and her hands began to tremble. The two men were surprised to see her bend towards the bottle of whisky, and her whole body shaking, she poured some in a glass and topped it in one go into her mouth. Even Ida seemed a bit lost.

‘What’s the matter, s-s-sweetheart?’ asked Don.

‘I’ll show you mine first,’ she said, and opening her bag with trembling fingers, she produced one gold earring, the one with a small crown with small chains dangling from its equator. It had somehow fell into Prakash’s hands. With her incredible memory Gina had remembered everything her Mauritian sweetheart had told her and had in turn told it to Katrina. Don stood up, and looked at it in amazement. He tried to speak, but no words would come out of his mouth.

‘It’s a piece of jewellery Dr Robertson, not an apparition.’

‘It’s magic! Teletransportation,’ said the Canadian without stammering. The others looked at him, expecting him to elaborate. He was in fact trying to, but could not speak. Ananda came to the rescue.

‘Open Don’s present,’ he urged.

It was the other one of the pair, the one which the remorseful Sukhdeo had travelled all the way to the harbour to return to Raju. Like hers, it had a small gold crown with small chains. Don watched her, like in a dream, as she held each one between the thumb and the index fingers of each hand and raised them for all to see. The gold in each piece was exactly of the same hue, and it did not need an expert to discover that they were made by the same craftsman. They were identical in every way.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 devishijaipur

Photo Credit:

CC-0 devishijaipur

‘This tells us without the shadow of a doubt, that you Don, have for ancestor, the villainous uncle of Katrina’s ancestor who demanded his pound of flesh when his cow died and had to be given one earring.’ They had shared whatever they knew of their histories with their Indian friend.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Yes, Prakash told Gina the same story.’

Katrina was a bit sorry that Don was a descendant of Sukhdeo, but one is not responsible for one’s ancestors. It was clear that Verity/ Devi was a descendant of Sukhdeo.

Ida had remained uncharacteristically quiet, but everybody almost simultaneously noticed that she had one of her superior smiles.

‘OK,’ she said, ‘are you ready for this?’ She stared at each in turn, and continued, ‘It meant little to me when I read uncle Aloysius’ account of some of the tales Ancestor Verity aka Devi aka Sundari told him.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Cat Burton

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Cat Burton