A small square berth, just enough for a small man to squat was all the space each man had to himself, and they were confined there except for short periods on deck every other day. After a seemingly endless ordeal, when the Metcalfe reached Hobart, a skeletal George Loveless, battered and bruised, in a state of shock, with scabs and sores all over was taken about thirty miles up the Derwent River and arrived at the government domain farm, where he had been placed. He was to spend a long time there, under atrocious conditions, and he had little hope of ever seeing his wife and family again. He missed them terribly, and often wondered if those powerful people back home had heard of the injunction that “They who God has united in holy matrimony, none must split asunder!”

The five others, including the three Jameses had a similar fate, except that they found themselves on the brig Surrey going to Botany Bay. Their journey was no less gruelling than that of Loveless. There they were placed in various places, to serve their term. Young James Hammett was sent to Hunter’s Hill, where he met his new master, Mr George Coldwell. The latter had spent some years with the East India Company in Calcutta, and was allowed to buy at preferential rate, the very big property here for which he had ambitious plans.

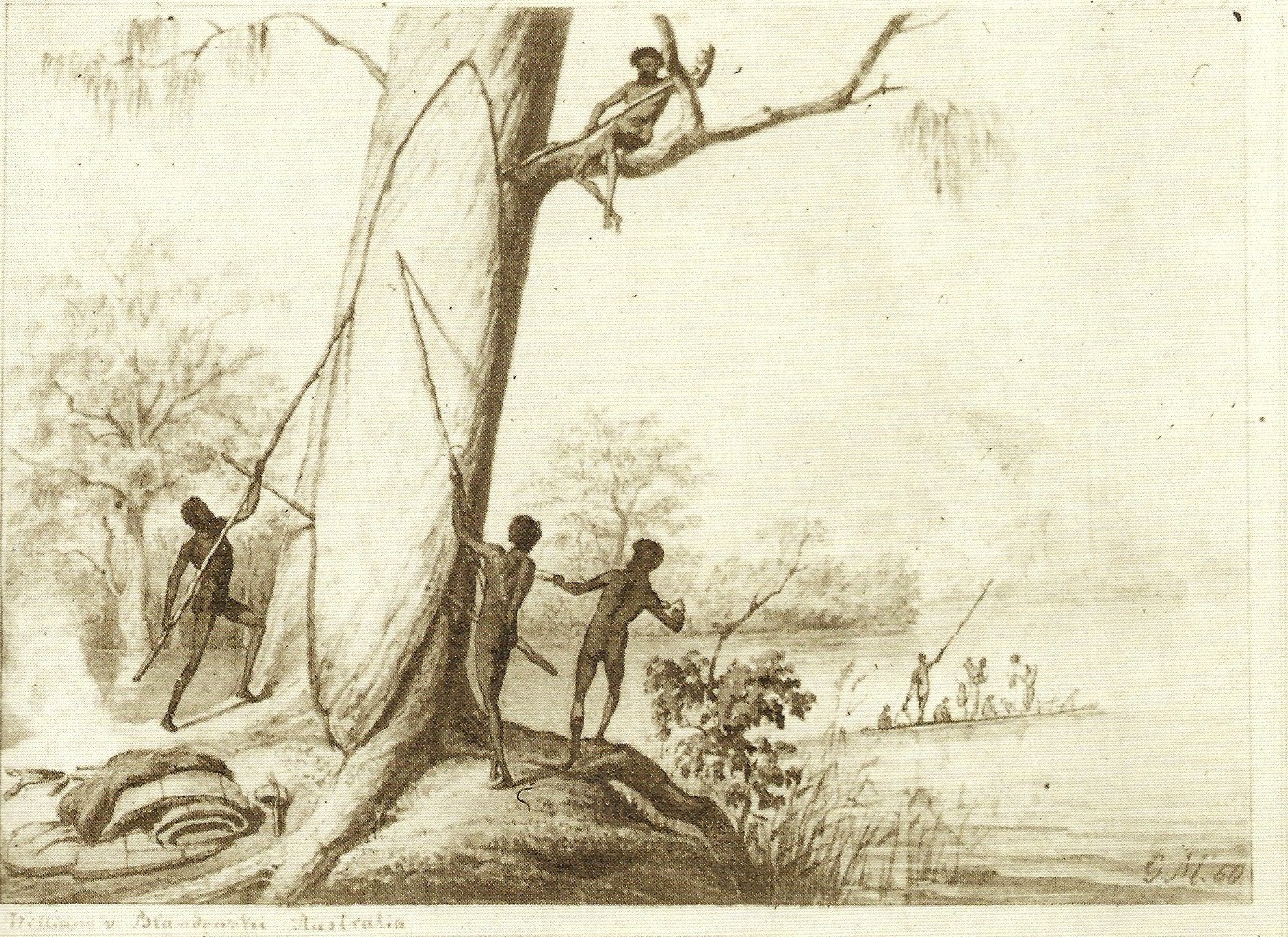

Whilst being taken to his new abode, James was greatly impressed by the landscape. Hunter’s Hill is the peninsula between rivers Lane Cove and Parramatta, which the Aborigines call it Mooroocooboola, which means the meeting of the waters. It is lush fertile territory, able to support crops of all sorts. The mangroves extended over large stretches of the shores of the rivers, and are homes to a variety of flora and fauna. James saw wallabies and spoonbills for the first time.

When the party of six convicts arrived in Taj Mahal in Hunter’s Hill and the constables were beginning to unshackle them, Mr Coldwell came out of the unfinished wooden mansion to greet them. He conversed with the constables and directly made for James, who very courteously bowed to him, smiling pleasantly and giving him every indication that he was going to do what was expected of him, and that the last thing he wanted was to rock the boat. He was not afraid of hard work, he would serve his sentence and the Good Lord would see to it that one day he be returned to his friends and family in Dorset.

‘So you are a troublemaker, I hear,’ Coldwell bawled out, ‘an arsonist who burn wheat fields, a wrecker of threshing machines, a swearer of secret oaths… I have read your papers, and I want you to know that I have little time for miscreants like you who aim to destroy the established order and who do not know their place. I am a fair man but I cannot abide indiscipline. I shall be keeping a close eye on villains like you.’ James was stunned. He wanted to protest that he was nothing of the sort, but the master was in no mood to listen.

‘In all fairness I must warn you, the slightest trouble from you, and you will be whipped to within an inch…’ James who had kept his head down all the time, nodded meekly, whereupon Coldwell put his whip under his chin and unceremoniously pushed it up in order to raise his head, so he could look at him face to face.

‘And answer me when I ask a question!’ he screamed, making the other convicts jump by the force of his delivery. James was not quite sure whether there was a question, so he said, ‘Yes sir.’

He met his fellow workers, all transportees, all swearing their innocence, but all said good things about the master.

‘Fair to middling’ said toothless Bob nodding gravely, James did not understand.

‘The conditions of work ’ere… fair to middling.’

Coldwell had a lovely wife, Amelia with whom, he was obviously very much in love. She was much younger than him, and they were childless. Amelia struck James as being a nice woman and noticed that she had a young convict woman, Annie Browne who was from the West Country as her maid. When called a Gyppo, she spat on the ground and said that yes, she was a Romany, but she was the granddaughter of the king of Gypsies, she was. After which she would cackle merrily. James was very much taken by the West Country girl who was seventeen or eighteen. She cast far from hostile looks at the young convict, and thereafter he sought out every opportunity of approaching her, but having decided that he would not draw attention to himself, he decided to bide his time. He expected that the bad start with the boss notwithstanding, his life in Hunter’s Hill did not need to be too much of an ordeal since everybody said that Coldwell was not a bad master.

Photo Credit:

Broadhurst, William Henry, 1855-1927 (public domain)

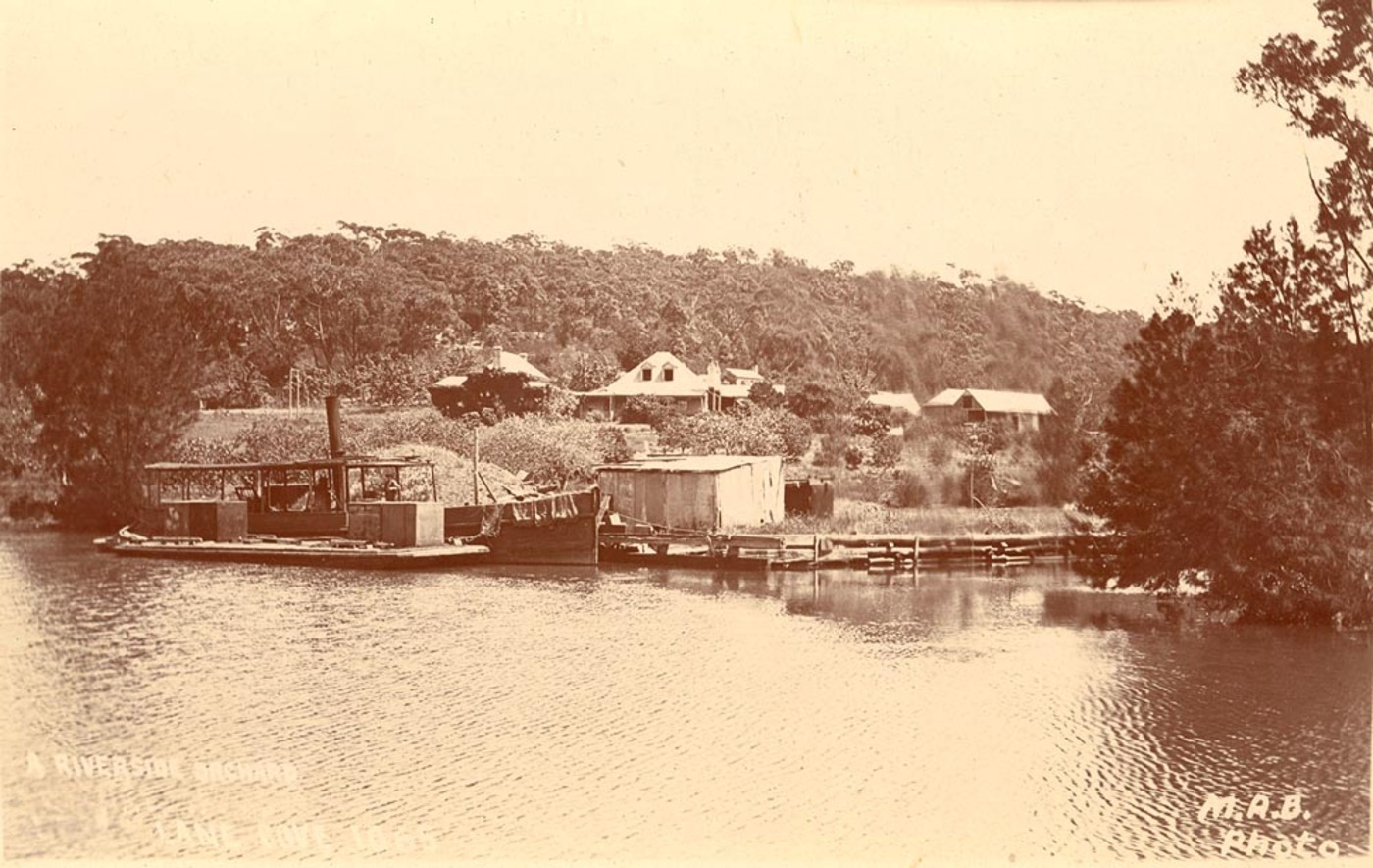

Photo Credit:

Broadhurst, William Henry, 1855-1927 (public domain)

The men lived in big dormitories which housed up to ten men, and had to work from six in the morning to noon, have a twenty minute break for a quick meal, and then work until sunset. Much of the work was of an agricultural nature, consisting of clearing the bush and forest for future schemes, digging wells for household needs and setting up an irrigation system which would harness the waters of the Parramatta to irrigate the plantations that Coldwell was planning, There was also the completion of the house, which the boss wanted to be the most magnificent mansion that money could buy. James was in a small team digging wells, after Johnson Johnson, an Aborigine water diviner had pinpointed where to dig. It was back-breaking work, but he was strong and healthy even after the four gruelling months at sea.

He was sweating profusely after a full hour’s digging, and taking a short breather when the master appeared from nowhere.

‘Ha!’ he said, ‘no wonder you thought your employer was demanding too much of you. You are a shirker, Hammett, aren’t you?’

‘No sir, just out of breath.’ Anybody could see the man was near exhaustion, but Coldwell looked at him poisonously and in a lightning move hit him on the face with the back of his hand, the blow sending him reeling as he tottered to the ground. James instinctively grabbed his spade, but immediately dropped it. Had he not stopped to think, it would have meant, at the very least, a one-way ticket to Norfolk Island. Perhaps even hanging.

Gradually he became used to the rhythm of life at Hunter’s Hill, although not to relentless and undeserved reprimanding. Coldwell had clearly singled him out and went out of his way to display his fangs to him, giving him the most unpleasant chores, swearing at him, sometimes hitting him with his fist or a horsewhip which he loved to flourish as he walked, decapitating dandelions and daisies. The convict had hoped that after a while he might believe the evidence of his own eyes and discover that he was neither a shirker nor a trouble-maker, but the boss seemed to have a blind spot when it came to him, and obviously saw what he had already chosen to see.

Still it was not always doom and gloom. One night as he was smoking his pipe underneath a strange tree which had fascinated him from the very beginning, he heard a rustle in the bushes and could not believe his eyes when Annie Browne appeared in the eerie moonlight. She beamed a smile at him as she came towards him, indicating that she meant to sit down by his side. She was wearing an attractive dress with large flower prints which she had clearly inherited from Mistress Coldwell. She huddled very closely to him, and he could feel her softness against his haunch and it was a very welcome, if troubling, sensation.

‘Since you are too proud to talk to me, I thought I may as well come talk to you,’ she said in her bewitching West Country accent. Her speech sounded like a song and her laughter its musical accompaniment. He stared at her obliquely, as if she had just cast a spell upon him — which she had. He tried to say something but only a falsetto sound came out of his throat, which doubled her merriment. He made a second attempt to speak but she stopped him by placing her hand to his lips, and he sat there saying nothing, savouring the moment. Then as his ardour began to rise, he slyly edged his haunch toward hers, in an attempt to get a better feel of her.

‘Oh you can if you want to, I don’t mind,’ she said, ‘you can even put your arms around me.’ James eagerly complied.

‘Aren’t you going to kiss me then, James?’ His mouth dried up completely.

‘Yes, miss,’ he said finally, but still doing nothing. Being called miss made Annie burst out laughing once more. Miss, she repeated, pretending to look behind her, where is she? But kiss her, he did finally. He put both his arms around her waist, and she extended her mouth to him, and they kissed, he inexpertly, but she obviously knew the ropes and directed her tongue inside his mouth fetching his. Since he left Tolpuddle in chains, this was the most fantastic thing that had happened to him. No, this was without doubt the most fantastic thing that had happened to him.

‘Can I smoke your pipe?’ she asked, but without waiting for an answer, she grabbed it and started puffing quite expertly. She did all the talking, telling him the story of her transportation.

‘I am no thief, never stole nothing for myself, I swear on the head of my poor little brother and sweet little sister… the good lord and Saint Sarah look after them now as their Annie is gone… they was always ’ungry, the mites. It were a sin to let ’em starve… I have stolen everything, bread, fruit, clothing, you name it. I always managed not to get caught, I am a crafty cow I am… But catch me, they did, in the end. A lousy ’en. That tailor said he’d take me to them if I got the ’en, you follow?’ James was completely lost. ‘They read the charge in court. Annie Browne, you are here to be judged on the very serious crime of stealing an ’en, valued at ten shillings and one penny, how do you plead?’ The way she spoke reminded him of the ringing of bells.

‘Hold on,’ cried James indignantly, ‘I don’t understand; a chicken valued at ten shillings and a penny? Crazy… You can buy a whole farmyard of chicken for ten shillings.’

‘And one penny!’ said Annie laughing raucously, pushing the convict playfully on the shoulder.

‘But sweetheart,’ she added, ‘did you not know it’s a crazy world?’ But whilst he was pondering on this profound statement, she interrupted him.

‘Now if you steal goods worth less than ten shillings, you do not qualify for transportation, see… So I reckon they must ’ave written down, one shillings and then somebody must ’ave looked at it hard and shook ’is ’ead. That won’t do, one shilling doesn’t warrant no transportation.’ Her eyes lit up with the hilarity that was announcing its impending gushing out. She now took a gruff male voice and an outlandish accent.

‘ “Ere boy, take this ’ere pencil and add a zero after the one.” ’ And she cackled merrily, ‘That’s ’ow come I’m ‘ere.’ James was indignant.

‘Do you mean those unworthy men —’ Annie’s laughter gained more impetus at this. She laughed and almost choking, she spluttered ‘Those unworthy men, ’e says… you mean those bastards!’

‘Well, yes,’ agreed James, who disapproved of bad language. When Annie calmed down, he asked, ‘But Annie, how can that despicable act make you laugh? You should scream and shout and spit in their faces.’ She stared at him, open-mouthed as if he had said something that defied logic, and grabbing him and squeezing him with all her might, she said, ‘On the contrary, I am grateful to them you sweet boy, for how else were we to meet?’ After a little pause, she looked at him in the eyes and whispered, ‘That you and I should meet here, was planned since before you and I wuz born, ye know?’

After a prolonged kiss, Annie became more subdued, and finished her tale.

Seven years in Botany Bay, the judge said, and here she was in her fifth year, two more to go, but Johnson Johnson’s wife had told her that she would never leave the colony alive, she said with a shrug. The proximity of warm soft flesh made him stop listening to her, and concentrate on the growing physical contact and the effect it was having on him.

‘There will be plenty of time for that later, I promise you James,’ she said merrily, ‘now I want to talk.’ James thought that he should say something too, but could think of nothing for a while. Suddenly his eyes fell on the moringa tree.

‘Funny tree that, isn’t it,’ he asked to cover his embarrassment.

‘Oh that tree… You are right, the master brought the seeds from India, it’s called a drumstick tree… got a funny name in Indian… he says it’s the most amazing tree in the whole world of… plants and trees… Its leaves are nice to eat when cooked, I like it, and these here,’ she said pointing to the long strange looking green sticks hanging down, are the drumsticks, and when you ’ave no drums to beat, you eat ’em… yummy… He says the flowers are nice too, but I draw the line at eating flowers, I do.’ And she told him a long list of magic qualities that tree was supposed to have, and promised that she would bring some for him to taste some day.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Scamperdale

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Scamperdale

They must have been together for almost two hours, to judge by the position of the moon in the sky, but it seemed like minutes to James.

‘I must go back now, sweetheart, or I might be missed… the missus must have a cup of cocoa at around this time…’ She paused, looked at him with a wicked smile, adding, ‘I know what you would like, but what sort of girl do you think I am? Opening my legs to you the first time we meet? Respectable I am!’ She started walking away, but turned round, winked at him saying, ‘Not really, not no more… not after what they did to me on the boat…’ James easily imagined what that was.

Meeting Annie that night, James mused, made the whole Tolpuddle experience, the arrest, trial and transportation, seem worth while. He repeated that like a mantra a few times, but before closing his eyes that night, he winked at the ceiling, shook his head, and said, ‘Not really.’

Next day, George Coldwell came towards him as he was working on the irrigation system, and his mistake this time was not to look up but continue with his work, and the boss took this as an affront.

‘You scum, have you no manners? Am I the boss or are you? Am I to be ignored, you dog?’

‘I didn’t mean to be bad-mannered, sir, I was working.’

‘Ha! You scoundrel, when my back is turned, you laze about, scratching your behind and picking your nose, and now you pretend you are working your guts out.’

‘I am sir,’ James replied in as a calm a tone as he could muster, ‘I am not a skiver’. He knew that he did not mean to be lacking in courtesy, but one is not born servile, one has to learn it, and he had not yet done so. Coldwell pounced on him, grabbed him by the scruff, pulled him up, dragged him towards a gum tree and pushed him against it, hitting his head against the trunk. James felt the blood rush to his head, and could not stop himself glaring at the boss in anger. The latter probably regretted his violent and gratuitous reaction, but he could not abide anyone looking at him like this.

‘You scoundrel, I am fast losing patience with you, and mark my word if this continues, I’ll arrange for a one-way ticket to the Island for you. Would you like that, you felon?’ This shook James, for he did not doubt that Coldwell could indeed arrange that, and he had heard a lot about that hell on earth called Norfolk Island. Its regime as a penal colony was the harshest that one could imagine, everybody said, although how anybody knew was a mystery, since once sent there, no one came back. It was claimed that it was specially designed for the “worst description of convicts” and for the so-called “twice-convicted,” which meant convicts accused of having committed further crimes since arriving in New South Wales. The guards were the most hardened jailers in the colony. The men were kept in irons at all times, even when they slept. Death is much preferable to a sentence on that island, everybody said. There was a story of a man of the cloth who went to the island to bring comfort to men who were due to be executed, and also at the same time to bring the glad tidings to those who had earned a last minute reprieve. When he told one man that the King had commuted his sentence, the latter burst into tears of despair, pushed his guard and sprinted towards the cliff from which he flung himself at the torrents below.

‘No sir, I will not like that, and will be grateful to you if you could forgive me for the error of my ways.’

‘Ha!’ said Coldwell rubbing his hands happily, ‘so you agree that you were wilfully rude to me?’ He had no choice but to nod his assent to an obvious untruth. His tormentor walked away, leaving him shaken. He felt it in his bones that Norfolk Island was only a matter of time.

That night he went under the drumstick tree earlier than usual to keep his tryst with Annie, but she did not turn up, and he went back to the dormitory with a lump in his throat, telling himself that he should not allow himself to be dragged into a one-sided passionate affair. Clearly the gipsy woman was a depraved creature who enjoyed trifling with unfortunate convicts for a little bit of sport. Or maybe she was playing hard to get. But she had made her mark, and he knew that he would find it difficult to get the saucy wench out of his system. But try, he would. He knew that he would not be able to stop himself going again to wait for her under the drumstick tree. Again and again.

Sure enough Annie turned up the next night, and explained that Miss Amelia had a headache the day before and wanted her to massage her neck and her head, and would not hear of her going to her room until she fell asleep. When she came out to meet him, he was gone. I’ll never ever doubt you again, he told a bemused Annie. That night, they lay together and had carnal knowledge of each other, and when she squealed with gratification, the inexperienced James was quite bemused. I love you so much, my James, she said earnestly, you are the only man I want, and I will never love anybody else for as long as I live, and that’s a promise and a Gipsy woman’s oath.’ Suddenly she asked if he had enjoyed it better in the past. James truthfully answered no, for he had never lain with a woman. She talked incessantly and then stopped.

‘I tell you everything, but you are quiet, you never say nothing about yourself,’ she said.

‘When would I have had the opportunity, Annie Browne,’ he asked, laughing. She stared at him open-eyed.

‘Do I talk too much then?’

‘No, you talk a lot, it is true, but it can never be too much, Annie Browne. Your voice is sweet music, not just to my ears, but I verily believe that it goes all the way and enters my soul.’ A true poet, you are my James, she said. She insisted that he told her about himself, and though he found it hard, he tried. He told her about Coldwell’s dislike of him, and that shocked her.

‘What are you saying? Master George is the kindest man on earth.’ James was surprised to hear that, but Annie gave him innumerable examples of his kindness. Mr Coldwell, she continued, is a learned man, always looking at his big books. He always had a kind word for her. No, she could not understand why he disliked James so much. She told how how devoted he was to his wife, about his interest in some Egyptian carvings found in Hunter Valley, how he was always talking about them to his friends, about his time in India, his plans for the the farm.

True enough, nobody had anything bad to say about his tormentor. He could not understand it, but it became clear to him that the people with the power had written him down as a dangerous lunatic, a rebellious subversive who needed to be on a short lease. Is there a way to influence Coldwell’s thinking about him? From what Annie had said, the lady was a sweet and good-natured person. She suggested that she could use her influence to get Amelia to speak to her husband in his favour. But he decided against that. If Coldwell finds out about the two of them, he might take it upon himself to thwart their burgeoning love.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Lip Kee Yap

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Lip Kee Yap

On Sunday the young lovers went for a walk on the bank of Lane Cove. They walked across the mangrove trees there, letting small crabs nibble their bare feet. At first they had the place all to themselves, but some native folks appeared, collecting crabs and weeds, plants, roots and small fruits. The children, their hair red with ochre, their eyes and nose dripping, laughed and shouted a lot, running all over the place, obviously enjoying themselves. At first they were wary of the white couple, but gradually they began to venture nearer them, and finally, noticing that their proximity did not perturb the pair, they began to run around them, touching their legs, screaming with laughter as they did so. They then recognised Johnson Johnson among them, and they went to meet him. He was very pleased to see them and offered them some dried fruits and roasted roots which they happily ate and enjoyed. Johnson Johnson sat down beside them and started speaking about his people, the Koori, their customs, what they ate, how they hunted, demonstrated how to use a boomerang, gave his personal one to James, which made the latter feel uneasy, as he had nothing to give.

Johnson Johnson proudly explained that his people were the original Australians. The ancestors, who were expert sailors, had used their canoes and then walked considerable distances over what is now the sea, and which was then land, after they kept seeing smoke, presumably from forest fires, from where they had settled (which James would later learn was Borneo, South Asia). It was about fifty thousand years ago, when an ice-age was ending, with ice collecting at the poles, which had caused a drop in the sea level of hundreds of metres, enabling people to walk on the bottom of what later became sea. Johnson Johnson told him about the Songlines. James would learn that people used regularly to walk the ninety miles from Australia to Van Diemen’s Land, for example.

Johnson Johnson tried to explain about the Koori concept of property, how they could not grasp the notion that anything could belong exclusively to one person. The edible roots under the ground, the fruits on trees, the wood for burning, the bark for making canoes, belonged to whoever needed them. How could they be the property of one person? He told them of the sadness of his people when the Englishman came and took possession of the land of their ancestors and drove them out. They did not even dream of asking for our permission to share it, he wailed. They listened carefully and sympathised with their plight. After a long silence, he looked at the pair, shook his head, and said wistfully, ‘And they even stole my name…’ James demanded an explanation.

‘My name is not Johnson Johnson. The white man stole my name and gave me an inferior one in its place,’ he paused, and looking away, said, ‘my true name is Birumbirra…’ James resolved not to call him Johnson Johnson again, but Birumbirra, but with everybody else calling him by his ‘inferior’ name, he somehow found this a difficult resolution to keep. From that day, Johnson Johnson and he became good friends.

When they got back to the compound, Bruce Powell, who was one of the group of convicts who had come over on the Surrey saw them and eyed them strangely. When James mentioned this to Annie, she said that Bruce had been sweet on her from the very beginning, but that she had not welcomed his attention.

‘I think he thinks he is in love with me,’ she cackled, ‘so young James, if you misbehave, I’ll know where to knock, eh.’

The weeks went by, each resembling the previous one. Christmas came and was gone without much fuss. Annie gave James leftovers from the turkey Coldwell had sent for from Cape Town (six months earlier) nurturing and fattening it. She almost always brought him things from the master’s kitchen. The mistress knew that she was seeing someone on the sly but did not ask questions. Annie craftily mentioned the name of Bruce now and then, hoping that she would think that he was her mysterious sweetheart, as a means of deviating suspicion from James, in the light of the master’s dislike of him. So nobody bothered James on that account.

One morning, James and Johnson Johnson were engaged in digging the canal that was to irrigate the plantations, when out of the blue the master came from behind and kicked him in his backside, shouting some gibberish at him. Clearly to the boss, he had done something wrong, but he never knew what. James turned round, and instinctively greeted his assailant with clenched fist, ready to pounce on him, before recognising who he was. The sight of this made Coldwell see red.

‘So now you are threatening to assault me, eh? You lay a finger on me you whoreson dog, and I will get you hanged! Come on.’

James immediately unclenched his fist, and shaking his head, said, ‘No, sir, no… I thought… I mean…’ Johnson Johnson gaped at the boss incredulously. Clearly he could not understand what possessed the big white man.

‘I would not dream of raising a hand to you, sir… it’s just…’ and he trailed off, unable to find the words.

‘Now, listen to me, and listen to me with both ears, I promise you that before three months, I will see that you get your just desserts.’ James knew he meant Norfolk Island! Or did he really mean to have him hanged? ‘We are too lenient to criminals like you here…’ and he went on incoherently for a bit before turning his back and moving away.

Norfolk Island! The man was obsessed by the idea of dispatching him there, and clearly he had the power to do so. That was when he made up his mind to abscond. He had heard stories of convicts who had done just that. Many had been recaptured, and with dire consequences. Some owners defied the law of the land and caused the renegade convict to be flogged to death. Many were sent to the notorious Norfolk Island, some were shot dead, some eaten by crocodiles, many got lost in the forest and starved to death, but a small fraction did manage to gain their liberty after all. James promised himself that he would be among those. He would plan it all in great detail, and he and Annie would find a place where they could live an idyllic life in peace, away from cruel masters. Members of the Friendly Society of Agricultural Workers, were encouraged by George Loveless to read, not only the bible, but works of literary merit. The Society was given a copy of Mr Daniel Defoe’s book, The Life and Most Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. It was a book James had read again and again. They said Australia was an immense country which had not been explored properly, and many people still believed that China was at one end of it. They would find a nice quiet place, away from the wicked masters, exploit the land, live on fish and game, roots and vegetables. It would not be a lonely life because they would have each other. Provided Annie was willing.

Johnson Johnson was clearly shocked by Coldwell’s treatment of his friend, and when James mentioned his certainty of being sent to the notorious island, he shook his head and tut tutted. He was sent there once to douse, and saw at first hand the treatment of the inmates there. No my friend, he urged, you must leave this place. James nodded, and admitted that he had been thinking the same thing. Yes, run away, there are many places, he said, you could also make friends with the Kouri people. We are very friendly if approached properly. He explained about their notion of territory. A person living in a place considers it to belong to his people, and nobody can cross into that land without their permission, but once it is granted, the visitor is treated like an honoured guest, even like a member of the tribe, allowed to fish, hunt and gather, offered help when needed. Anybody arriving in a Kouri site without permission is deemed to have broken the law and can be severely punished.

‘You mean if I run away to a faraway place which might be someone’s territory, I might be killed?’ Johnson Johnson pursed his lips and made a non-committal gesture, before adding, ‘But Kouri people do not kill for fun.’ He explained that the custom before going on a trip, is to get message sticks given by someone known and respected by the tribe. The traveller with the appropriate message stick is granted entry and offered all help possible.

On hearing this James became very depressed, his dream of freedom evaporating like the morning mist when the sun started rising.

‘I am a respected elder,’ said the Aborigine smiling, ‘and I can give you a message stick…’ James had never been subject to such a sudden change of mood. He had witnessed on many occasions a flash of lightning in a clear blue sky, followed by a downpour, but never the opposite, the sky suddenly becoming blue after a thunderstorm.

‘Can you really? Then I can go thousands of miles from here and —’

‘No,’ his friend said smiling sadly, ‘I may be a respected elder, but not by everybody…’

‘You mean he’ll find me…’

‘Maybe not… have you heard of Illiwarra?’ James had not.

‘I was born there… I am respected there… nice place. Lake Illiwarra,’ he explained, ‘is a salt water lake, and teems with fish and crabs and edible algae. Wild geese,’ he added, ‘loved the area, and I will tell you how to find goose eggs, they are very good to eat.’

‘Will I be safe from Coldwell there?’

‘He is busy here… he will not trouble you there… it takes days to get there… on foot, maybe fifteen…’ Johnson Johnson seemed deep in thought, then suddenly added, ‘Quicker if you use canoe…’

Johnson Johnson told him about the richness of the region, and it did not take him long to make up his mind. This was where they would go. At first Annie was taken aback, but understanding James’ fear, she never hesitated about throwing her lot with him. I’ll go with you even to China, she said merrily. Johnson Johnson’s help in the plan was crucial. He offered to arrange for his friends in Lane Cove to make a bark canoe for the runaways. Bangalay, the best canoe tree providing excellent bark abounded in the area, he said. They will also provide the couple with the best goinna to paddle the craft, and he would instruct them in that art (“one paddle in each hand, and one stroke at a time”). He would make a list of possible dangers and tell them and how to avoid them. Even a child, he said, should have little trouble keeping the craft afloat and moving in the right direction, adding with a smile, a Kouri child, I mean. In the meantime he would prepare the message stick. The pair planned their escape carefully. Whilst out courting, they had found a crack in the rocks, and decided that it would make an admirable cache for the things they planned to take with them. Annie deftly deviated the things they might need to make their lives comfortable in a faraway place: kitchen things mainly, blankets, needles and things like that. She also thought of taking some seeds from the drumstick tree. James on his part, managed to steal a few tools, rope, nails, hooks for fishing and similar things, and when they met in the night, they would go to the woods and hide these precious lifesavers, with a view to taking them on the canoe which was in an advanced state of construction. They were happy that they had thought of everything that they were likely to need in the wilds. Johnson Johnson explained to them how to catch and cook turtles, how to spear fish and trap wild fowls, although they never had the time and opportunity to put the knowledge into practice.

Annie was sorry to be leaving Miss Amelia, for she was fond of her, and knew that she would be missed too, but the moment she had agreed to go with James, there was no looking back. She had always been full of optimism even when she did not know where the next mouthful was coming from. If there were risks, she was willing to take them. If anything went against her expectations, she took a deep breath and looked at alternatives. I never cry over spilled milk, she often said, what’s the point?

Over a month passed before they were ready. Johnson Johnson had said that their craft was ready in Lane Cove, that they could pick it at any time, but had warned about stormy winds. Annie, ever optimistic, said there was no point waiting any more, that they should go immediately, but the more cautious James said it was best to be guided by the wise Kouri man. So they waited for Johnson Johnson to pronounce everything, specially the weather conditions, propitious.

A week later, when the family was going to mass in the chapel which Coldwell had had built in the grounds of Taj Mahal farm itself — the servants and convicts were expected to attend a later service — the pair sneaked out. Nobody saw this as anything unusual, except Bruce Powell who followed them for a bit, and then asked them where they were going. James did not know what to say, but Annie winked at him suggestively, and playfully pushed him away.

Bruce suspected that something was afoot, but had no idea what it could be. He would have liked to go to Coldwell and have a word in his ear, but knew that if the others found out, he would be called a snitch. All day he watched for their return and when they did not, his doubts were confirmed.

The runaways reached the place Johnson Johnson had indicated, the large red rock next to a massive gum tree where the river bends, and waited there. A child seemed to be waiting for them, but the moment he saw them he bolted. A few minutes later, three men appeared, and James showed him a message stick his friend had given him. It was not really a stick, but a piece of bark on which there were some etchings of symbols. The men studied it, passing it round, nodding to each other and exchanging a few words which the pair understood not a word of. The oldest man signalled them to follow them, and after no more than a few steps, one of them began to uncover some leaves and sticks, revealing the canoe. It looked flimsy but James knew that his friend would not order a canoe that was not seaworthy. They thanked the men, who comically repeated the “Thank you,” many times and helped put the stuff on board. When that was done they rubbed hands with their benefactors and climbed on board and began paddling away.

It was just as easy as Johnson Johnson had said.