Book 2 Chapter 5: The Bagne

(Mauritius, 1790s)

This chapter is dedicated to Laxmi Bhatt who worried about the fate of the African warrior.

The Bagne was a desolate area on the quayside just outside the precincts of the harbour. Its construction was still incomplete, and it only offered basic facilities, and the security only worked because of Grapouille’s ruthless regime. The area was spacious, and there were plans to build a Military Hospital adjacent to it. A high wall was being built to surround the prison in order to make it escape-proof, and all the present inmates, were employed in its completion. Governor Grapouille prided himself that on his watch, not one slave had managed to run away, and promised to improve on this record.

The moment Midala entered that grim place, he started looking around to find chinks in the security system. He discovered that the place was guarded by armed men, following each inmate like a shadow, and was told that they were instructed to shoot to kill anyone attempting escape. The regime of punishment for so-called recalcitrants was outrageous. They would be made to stand in the burning sun, holding a massive rock just over their heads, without water and deprived of food and sleep. Inmates worked in groups of four or five chained together at the feet, breaking rocks destined for the completion of the walls. Even at night they stayed chained. His heart sank. A planned escape seemed almost out of question. Any breakout could only be envisaged on the spur of the moment, if an unexpected opportunity arose. But a good soldier plans for all possible contingencies.

Grapouille was a drunk who swore at the men whenever he had the opportunity and enjoyed kicking them for no reason at all. He had carefully picked men speaking different languages in each group, in order to make it difficult for them to conspire. Most people, like Midala, still had difficulty coping with kreol. In his group, he was the only Chopi, the others were Malagasy, Anjouani, Swahili-speaking Zanzibari and a deaf mute. Another group consisted of a man from the Guinea coast who spoke Mandingo, a Malagasy speaker, a Shangaan man and an Anjouan man from the Comoros. But no power on earth can stop people from communicating. At first, inspired by the deaf mute, the men used sign language and made themselves understood reasonably well, and it did not take long for them to develop a common language which everybody understood, each one having supplied some kreol vocabulary known to him. Besides the guards manifested their disapproval by hitting them with the butt of their rifles if they saw the men attempting to communicate

Although the work was back-breaking, the men worked cheerfully, heartened by the sight of the calm blue sea, and soothed by the music of the waves crashing on the beach, for they knew that it was best to put up with hardships, or one ends up completely overwhelmed by them. Pastitatane, the Malagasy man was very proud of the fact that he could speak and write French, and it was Midala who suggested that he should teach them. He was delighted to do so, and often, when the guards were not actively watching them, the man from the big island arranged the small stone debris into the shapes of the letters of the alphabet. At the approach of a guard, they would cleverly mix up the pebbles as no one had to tell them that the authorities would deem reading and writing subversive acts.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 Campofant

Photo Credit:

CC-0 Campofant

Daily Midala looked at the sea, wondering if it provided a way of escaping, but with the heavy chains that he had to drag at all times, excellent swimmer though he was, he knew that it was a vain hope. They were tied together in fours even when they slept, the two middle persons with both hands tied to their neighbours on either side, and the two people at the ends had each free hand chained to a massive log by means of a heavy lock. The first step in any night escape necessarily had to be finding the means of freeing themselves from their chains. Four men weighed down by heavy appendages would not go far if they attempted to run away in broad daylight. At night they were almost completely immobilised having to empty bladder and bowel on the spot, like on the slave ships.

Everybody shook their heads in sorrow when escape was mentioned, agreeing that it was an impossible dream, but Midala, the man who had performed a number of miracles in the past, said not to despair, an idea might come to them when it was least expected.

He had wondered how the big rocks they had to work with reached the bagne, and was pleased to discover that oxcarts regularly arrived at the place with big rocks culled from the base of the Signal Mountain which they could see from their place of incarceration. One morning when six carts appeared on the precincts, the prisoners were required to unload them and take them to an area where they would be broken up by means of heavy iron mallets, hammers and chisels. It was the only time that the chains were completely removed from them and they were separated from their team mates. He thought that this might provide the means of escape that he had been looking for. However with the guards following the bagnards like shadows, their pistols poised to shoot, that did not seem viable. Still he had only been one week into the new regime. Things might develop, it was too early to give up. As a strategist who had planned, fought and won wars back in Inhambane, he was used to studying the weak points of the enemy, and this was certainly one of them. It might or might not prove decisive, and he would revisit it later.

Paradoxically, a chink of light emerged from the complete darkness in which they slept at night in their cubby holes. Because they were chained and tied, the guards, feeling safe, acting against orders, often went to sleep. The fatigue caused by the heat, compounded by the large quantities of rum which they consumed when their superiors were not looking, found them exhausted at the end of their long day. They could be heard snoring the moment they had moved to the end of the room. They usually took position near the door, where they could breathe fresh air, and benefit from moonlight when the moon was out as the atmosphere inside was almost unbearable.

An assault on the guards would not be easy to organise, but Midala had mulled over the possibility of an insurrection, which might mean certain death for at least some, if not all of their numbers. If he could find a way of minimising the casualties, he would talk it over frankly with his fellow bagnards.

Weeks went by, and although he rarely thought of anything else, he made no progress. It was like the complete darkness of the nights in his quarters, but with no compensating rays of light sneaking in at dawn through the cracks in the walls. The inmates were good company in spite of their wretched conditions. At first, the deaf mute seemed to have the most optimistic outlook in Midala’s group, although he had difficulty communicating with the rest, he had frank innocent eyes and he smiled a lot, and everybody liked him and felt protective towards him.

To everyone’s surprise, one day, as the oxcarts laden with rocks had entered the gates and everybody was unchained so they could unload them and take them away, the deaf mute began making desperate efforts to speak, with only pathetic incomprehensible guttural sounds coming out of his throat. He began gesticulating, turning his head left and right in what appeared comical to everybody, making frantic signs, which nobody understood. The others laughed, the guards the loudest, but Midala was perplexed, it was so unlike the fellow to behave in this strange manner. He was obviously trying to say something. If only Midala knew what it was.

They were soon to discover the reason, for suddenly the poor fellow, who was on his way towards a cart, turned round and started running in the opposite direction, towards a breach in the wall.

‘Stop, or I shoot,’ a guard shouted. It is doubtful whether he would have stopped even if he had heard the order, but he obviously did not, and Midala saw his jailer raise his gun, cock it, and without thinking, he flung himself at him, both crashing to the ground. But another guard did the job, fired his gun, and the deaf mute fell down, blood gushing out of a large hole in his back. Within minutes he was dead. It took three guards to neutralise the inflamed Midala, by kicking and beating him to a pulp.

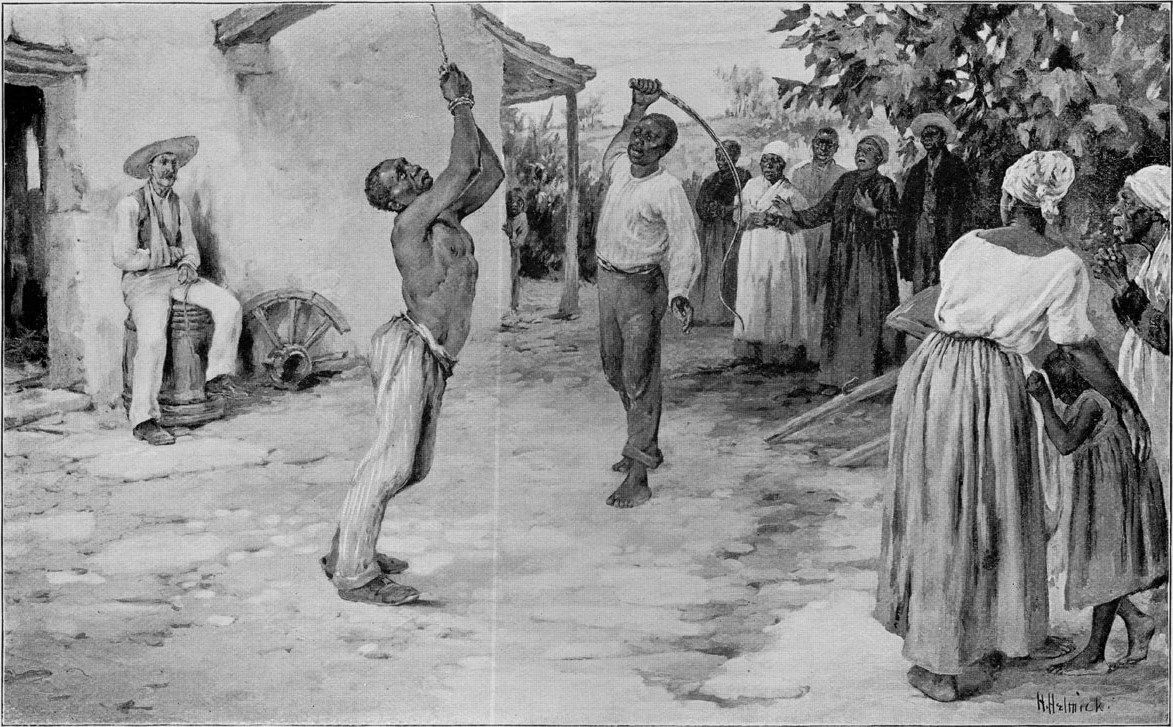

Photo Credit:

Whipping a Slave, from Mary Ashton Rice Livermore, The Story of My Life (Hartford, 1897) (Public domain, copyright expired)

Photo Credit:

Whipping a Slave, from Mary Ashton Rice Livermore, The Story of My Life (Hartford, 1897) (Public domain, copyright expired)

Unconscious, and covered in blood, he was dragged by guards, chained and dumped in a small isolated stone cell, known as a cachot, as the other inmates watched in horror. The square base was so narrow that there was barely enough room to sit on the floor. To sleep, he had to lie across it diagonally, bending his knees. Even then, every time he moved in his sleep, he knocked his head or some part of his body against the stone wall. There was a very small vent at the top, and the massive wooden door was secured at all times. Midala was left in it for the rest of the day, with no food or water, and no one attending to his wounds. An armed guard stood outside. The heat was unbearable, and having bled profusely, he was more or less unconscious the first day, his throat parched. He had soiled his trousers with urine and excrement, and these mixed with the smell of blood and sweat, made for a stench the like of which he had not experienced even in the hold of the slave ship. During the crossing, there was at least a breeze which brought in some welcome fresh air, diluting the nauseating stench a little bit, but in the confines of the narrow cell, no such relief was available. On the ship, he had held the firm belief that the stench was due to the excrement and odours of others, for man has this ludicrous belief that his own aren’t that bad. He had even sometimes relished the smell of some of his bodily excretions. However, now that he was the sole producer of these execrable emanations, this illusion was finally laid to rest. There was not a single thing to cheer one up, the darkness was almost total. He could see nothing, hear nothing. Smell was the only sense still functioning, but all it had to convey was this execrable stench. A baby in its mother’s womb is at least able to hear the rhythm of its mother’s heartbeat. Suddenly he became aware of the faint sound of the waves crashing against the beach, as if they were miles away and found it very soothing. All the time he had been working in the proximity of the sea, he had hardly ever paid any attention to the waves, but now, it was his only contact with outside reality, and he found some peace listening to its rhythm. Without it, he might as well be dead, he thought. Conscious of the life-giving properties of sound, he began to hear the gentle whistle of the wind among the vegetation. He had tears in his eyes when he was woken up in the morning by a dawn chorus of birds that he could not see.

In the afternoon, he was dragged to the office of the Surintendant Grapouille whose cruelty was considered an asset by his superiors. Playing with his whip, which he carried with him at all times, as if it was an extra appendage, he listened in silence to Caporal Goelard’s account of the constant insubordination of the bagnard from the beginning. These were all lies, as Midala had decided not to do anything to attract attention. Mequereau, the guard who was prevented from shooting the deaf mute told another lie. Midala having caught him off guard, he said, had snatched the gun from him and would have shot him dead, were it not for Goelard who wrestled with him and succeeded in disarming him. Other guards corroborated their stories. When they had finished, the Surintendant beckoned Goelard. The latter smiled and strutted towards his superior, expecting a pat on the back, but to his shock, the moment he was near enough to the Colonel, the latter hit him across the face with his horse whip. He made futile attempts to parry the strikes with his arms, but his incensed superior continued lashing out, seemingly forgetting Midala.

‘Do not talk to me of insubordination, you arse-scratching halfwit. You have powers, you dog, and any insubordination is entirely due to your uselessness. It only means that you have not been doing your job properly, full stop. Show some initiative, man!’ The colonel then took three steps towards Midala, who, downcast and exhausted by the beating, was looking at his feet. Putting his whip under the slave’s chin, he lifted his head up.

‘Look at the state you are in,’ he said, ‘you people are worse than animals, dirty smelly swines all of you. What have you got to say, eh?’

‘Oui missié,’ he said almost inaudibly. Grapouille made a long rambling speech. He had been sent by the his majesty, halfway across the world, from the most civilised country in the world to spread light where there was darkness, but it was like filling a basket with sea water. He had said as much to Sa Majesté when he was invited to Versailles, he boasted, safe in the knowledge that no one was going to contradict him in this untruth. But does anybody ever listen to him? Even the guards thought that he was losing the plot. After going on like this for a quarter of an hour, he got back on track. Midala was to be deprived of clothing and bedding, since he thought that their purpose was for shitting and pissing into, and kept in solitary confinement in the cachot for fifteen days, hands and feet chained, with no more than bread and water, and with twenty-four hour surveillance outside his door.

‘Should he attempt anything on your watch,’ he warned the guards solemnly, ‘I will peel the skin of your arse and stuff it into your useless mouth myself.’ After a pause, whilst the guards were taking on board what he had just said, he screamed at the top of his voice, ‘And don’t anybody dare come to me and talk of insubordination!’

The guards seized Midala with singular viciousness, and were on the point of leaving, when the Colonel stopped Mequereau with his whip on his chest.

‘And you, Mequereau, what kind of nose-picking, pig-dirty, shit-eating piece of vomit are you, allowing an unarmed black savage to disarm you? What happened to your balls?’ He directed his whip to that area, poking it repeatedly. Mequereau was too shocked to react, and as he expected, this was followed by a cascade of blows on his face inflicted by the back of the Colonel’s hands, and one final vicious kick in his backside just as the man thought that his ordeal was over.

The two men did not have to collude to come to the decision to make the slave’s life hell. This was exactly the chink in their armour that Midala was praying for. The men, properly armed had twelve hour shifts, standing guard outside the cachot, and had no business going inside except to pass on to him his meagre rations twice a day. The stench alone, would have been a good enough reason for them not to venture inside, but they had a gnawing necessity which transcended all other considerations, to vent their hatred on the man who had been the cause of their humiliation, and to repay for their shame in the same currency. And what more satisfying form was there than sexual degradation! As a result, when they were bored witless, walking round and round the cachot, they thought a little fun would not come amiss. The first time, it was Goelard who set the benchmark. Having paced up and down for hours on his first shift, any idea entering his thick head quickly rushing out for fear of solitary confinement. He decided to go in and have a look for himself and indulge in a bout of taunting. Midala was a pitiful sight indeed. His body was covered in scabs, and unable open his bruised eyes he did not bat an eyelid at the guard’s entry. Goelard pretended that he was going to faint and put a hand to cover his nose, decrying the filth of savages who knew nothing about cleanliness. He bent down, poked the the poor man’s penis with his gun, and lifting it scornfully, he remarked on its extraordinarily small size. He expected a man like him to have an organ to match his pride, he cackled. If your mouth was not so dirty with its sores, I would make your dreams come true, Cacapou, and make you suck my dick. You would like that, wouldn’t you, cock-sucking mother fucking blob of vomit? He kept swearing at the prostrate man, and spat a big gob of phlegm on his face before leaving. When he left, Midala smiled for the first time in a long time.

Goelard and Mequereau must have exchanged notes, for next day, the latter came in, and re-enacted the same little scene that his colleague had put on the day before, except that this time, when suggesting that Midala sucked his cock, he unbuttoned his trousers and displayed his erect organ. Yes, thought the humiliated man, I can hear the blacksmith forging my key.

The next day was a repetition of the previous day, but Goelard went one step further.

‘You know, Cacapou, tell me what’s to stop me dragging you out and shooting you like a tangue, and then tell the Surintendant that I had to shoot you for trying to escape? You heard what he said? Show initiative, man!’ He did not know what to say, and kept his mouth shut. Whilst Mequereau had just cackled obscenely, Goelard kicked him a few times.

For three days, he did not have the strength to move. Although it was usually quite torrid inside the cell in the daytime, nights could sometimes be fresh enough for one to need a thin blanket, specially in view of his nakedness, and he was unable to get a good night’s sleep. On the fourth day however, he was able to stand up and do some exercise, which consisted mainly of jumping up and down. That was quite a strenuous thing to do, in view of the heavy chains, but he wanted to stretch himself to his limit. His aim was to get enough strength to hoist himself up so he could reach the vent, and study the terrain. The insult and sexual innuendos became a daily routine, and so far neither had tried to translate their words into action, but to judge by the more and more obscene gestures the two depraved men were making, as well as their excited state, Midala feared the worse. He was quite apprehensive about that possibility, and did not know whether death might not be the best thing that could happen to him. He had no strength left. For the whole of the morning he was prey to this defeatist mood, but when he heard the guard outside approaching the door, he suddenly perked up. I am a fighter, he told himself, have always been, and the Great Spirit willing, I will never give up the good fight. He imagined that when the guard did decide to make good his threat, he would refuse and that his sexual frenzy might well make the man carry out his intention of shooting him. All this was out of his hands, he decided, so he was not going to worry about it.

The cell was quite high and the vent near the ceiling way beyond his reach. The wall made of stones cemented together, was fairly smooth, and did not provide any foothold. He had heard snoring and guessed that the guard normally had a nap on hot afternoons, in the shade of a bois noir tree, a little way outside the cell, so he planned to use his chains to make a cavity in the wall, below the vent. Having picked up the pattern of the waves, he found that short sharp strokes at the point where two stones were cemented together, coinciding with their crashing disguised the noise. He was pleased to find that the cement was easy to breach, and this provided the means of damaging the stone. By dint of constant tapping, the stone started frittering away and in one afternoon, he managed to make one hole big enough to accommodate a big toe. The next day, he made this bigger, and then started working on a second breach. Afterwards the operation became more arduous. He had to contend with the cumbersome chains as well as maintaining his balance on the precarious footholds that he had made. He must have slipped hundreds of times but he expected that. After one week, he ended up with four footholds and finally succeeded in hoisting himself up with his head reaching up to the level of the vent. He was filled with joy as he saw the sea, to which he had imparted almost human characteristics, since it was the only “one” who talked to him, in soft melodious whispers and had helped defeat the vigilance of the guard outside. In a week, he had forgotten the sea was so blue. He also acknowledged a debt to the filaos on the beach for providing an accompaniment to the music of the waves, as the wind blew through their needles. As a child he had wondered whether it was trees that made wind, or if it was the wind that made the leaves flutter. The position of the cell was such that the vent afforded him a limited view of the area leading from the bagne to town. He made a mental note of the breaches in the unfinished wall. A short distance away, just past the boundary of the bagne, on some as yet unused land, earmarked for a military hospital, he saw a strangler tree. At some distance he saw a few people going about their businesses, and guessed that with the activities of the ever busy harbour and the many small businesses associated with it, there would be many more around, and hoped that any escapee would inevitably meet people, some of them officials who would undoubtedly challenge him. But the difficulties were not insurmountable if he took into account all possible pitfalls. In any case there was always an element of risk, which he, as a soldier, knew he had to take.

He was not able to elaborate a complete plan, as he was not in command of all the elements involved, and accepted that he would have to trust the Great Spirit and improvise when the time came, as he knew it had to. He did not have to wait long. On the very next day, Mequereau came in, and although it was dark and cloudy, he could see the glistening face of the guard. The vent provided a little light, and he could see the man’s erect cock protruding out of his trousers.

‘Today’s the day you have been waiting for, Cacapou,’ he cackled wickedly, ‘I am going to make your dreams come true, get on your knees.’ Midala did as he was told, as he did not want to be beaten black and blue, having decided that he had to be physically whole and fit in order to do what he had in mind. He knelt down.

‘Here, take it in your mouth, make me see paradise.’ He thrust his organ forward with a quick movement of his pelvis, and Midala opened his mouth. The man gave a sigh of pleasure, but this immediately turned into a shriek of pain, as Midala suddenly bit on it with all is might. He had not expected the amount of blood which filled his mouth instantly. The man squealed like a pig, fumbled for his pistol, found it, let it slip through his trembling fingers, and the bagnard held on increasing the pressure of the bite. He was surprised to find that he had severed the cock, and spat it out with revulsion. The man, whimpering like a beaten dog, crashed on the floor trying to stem the flow of blood from where his manhood used to hang, almost lifeless, his body subject to spasmodic little jerks, like a dying chicken whose head has just been cut off. He was going to leave him like this, but knew that he would bleed to death, slowly and painfully. As a soldier he had often had to finish off an enemy out of pity, so he strangled him. It was war, and you had the right to kill your enemy on the battlefield, and if you could make it by inflicting minimal pain, it pleased the Great Spirit. He found all the keys he needed in the coat pocket of the dead guard and used them to free himself from the chains.

He then undressed the dead man, spat out the taste of blood, took his blood-soaked clothes under his arm and made a dash for the beach through a gap in the unfinished wall. He did not stop until he was out of the boundary of the bagne, at the level of the strangler fig tree that he had spotted earlier. Fortunately there was nobody around, and he was able to wash the blood off the clothes in the sea. He had already made up his mind that the strangler fig was going to be his gate to freedom. It was surprising how often that blessed tree had featured in his life. He was now certain that had he been allowed to carry out the operation to stop the attackers in Inhambane, the course of history would have been very different.

Photo Credit:

CC0 sandid

Photo Credit:

CC0 sandid

He imagined that when Goelard came to relieve his colleague, in less than an hour, he would raise the alarm and all hell would break loose. Grapouille, who prided himself on the fact that his bagne was escape-proof, was certainly going to erupt. Midala was going to hide up the tree, at a stone’s throw from his office, wait for the dust to settle, and when it did, he would choose an appropriate moment to come down and make his way to Madame Agathe.

He grabbed a hanging root, coiled himself round it and hoisted himself up with an agility that surprised him. When he reached the top, he found a flat spot in the crook of a branch and sat there in comfort. It did not take an hour for the alarm to be raised, but safely ensconced among the thick foliage, he was able to watch, undetected, the clueless guards running aimlessly in all directions, often colliding with each other. At one point even Grapouille himself appeared, shouting hysterically, causing even more mayhem. When the washed clothes of Mequereau had dried, he put them on and waited for sunset. The crowd milling about in the area grew thinner at the approach of the dark, and he slid down. Since he had not seen any guards in the last hour or so he had assumed that they were looking elsewhere, and had a shock when no sooner had he come down than he came face to face with one. He was surprised at his quick-wittedness, but as he was wearing a uniform, he was well-equipped to play the part of a pursuant, and wordlessly pointed in the direction of the unfinished hospital.

‘You go that way then,’ said the guard pointing to the right, ‘and I will go the other way, we’ll nail the bastard yet.’

He ran towards the non-existent runaway, but the moment the guard was out of sight, he slowed down. He found that even if Mequereau’s uniform was on the small side, people in town paid no attention to him, and he reached Madame Agathe’s house in Roche Bois without difficulty. Strangely, she had already heard of the to do at the bagne, and was surprised and delighted to see the legend who had become the first man to escape from it. She treated him to a feast, which was also attended by Azoline who had been picked up since last time, but had done yet another runner. History books would proudly recount later that in seven years, she escaped from her masters a total number of twenty four times.

‘What are your plans now?’ Madame Agathe asked him.

‘Why, find Matamba, of course.’

Agathe shook her head sadly, and said that it was madness, for after what he had done to Mequereau, catching him would be a top priority, and once he was caught, there was only one possible outcome, and he knew what it was. He said nothing, but was deep in thought.

No, Midala would never contemplate running away. He had failed everybody so far, had not been able to defend his tribe against Ibn Qalb and Flyte-Camilton. He had done nothing for his fellow victims on the slave ship, except perhaps send some men to an early grave. There was a war between the plantation owners and his fellow victims, and he had to stay to fight. He had always known that in spite of her frivolous exterior, Agathe was a woman of wisdom and acute sensibilities, and was not surprised when she spoke.

‘My friend, you are a soldier, yes?’ He nodded sadly.

‘What does a soldier do when he knows that the odds are stacked against him?’

‘A soldier’s duty is to die for the cause he has espoused.’

‘Tell me one thing, how can your certain death help anybody?’

The military strategist said nothing for a while.

‘What else can I do? I can’t just abandon Matamba.’

‘From what you’ve told me, Matamba is someone who is well able to look after herself… for all you know, she might be at peace now, and you would certainly expose her to danger, have you thought of that, warrior man?’

There are many things you can do, stupid man: you can go back home and see your children and their children, help protect them. And I’ll tell you what your escape will do, added the formidable woman, it will bring some joy to those miserable slaves toiling from dawn to dusk with no hope of release… you will become an icon, Midala. I will personally tell everybody about how you escaped, show them that the white man is not invincible. Agathe knew that she was on a winning streak, and as someone not averse to repeating herself, she went on for a bit.

‘You may be a great warrior,’ she said finally, ‘but your strategy is limited to the battlefield, my friend. You forget that there are other arenas. Morale is very often more important to combatants than weapons, don’t you agree?’

Midala was known for his determination, but in the end his benefactress managed to talk him out of his madness, as she called it.

‘And you are in luck,’ she told him, ‘I am at the very moment able to organise a passage back to your part of the world, believe me, that’s the only thing left for you to do.’

She warned the man that if he let that opportunity go, he might live to regret it, and strongly advised him not to let that chance slip away.

One of Agathe’s lovers was Pillai, an Indian chef from Pondichéry on board the French warship Le Quimper. It seemed that even the King in Versailles had sampled his magic menus, and had dubbed him Pillai Roi du Pillau! Or so Pillai told everybody. He never failed to pay her a visit whenever he touched Port Louis, which was twice a year, and his ship had cast anchor in Port Louis harbour two days ago. Wasn’t that fortuitous? Agathe asked the warrior, does that not mean the Spirits mean you to escape?

‘Pillai is devoted to me.’ she explained with pride, ‘he will never refuse me anything.’

Next day, on cue, Pillai called.

‘Just as we were going to bed,’ she recounted to Midala later, unable to repress her triumphant laughter, ‘I said, Pillai, wouldn’t it be wonderful to smuggle a notorious repris de justice on one of the King’s own warships? She explained to the fugitive how she had always loved to make people in authority look like fools.

‘Pillai I want you to promise me one thing.’

The cook’s reply was a standard one. ‘My dearest woman, Pillai doesn’t need to know what it is, it is accorded.’

‘Are you sure you aren’t going to change your mind?’

‘I know I am going to regret this, but it’s a promise, Pillai never changes his mind.’

‘I want you to meet a friend of mine after you have taken me to paradise and back… like no one else can’.

She got Azoline to call Midala who was in another room to join them. She made the introductions, and gave him a detailed account of who he was. Pillai started to feel uneasy, but said nothing.

‘I want you to take this man on board your ship and drop him near Inhambane,’ she said in the most matter-of-fact manner, as if someone was asking his coachman to drop a parcel at a friend’s house. The magician of the kitchen was shaken.

‘Pemba,’ he said, ‘that’s the nearest…’ Then he stayed silent and pursed his lips thoughtfully, obviously troubled, and finally he shook his head wistfully.

‘Do you realise what you are asking Pillai to do, ma chérie? Carry an outlaw who has killed one of his majesty’s soldiers on a ship of the King of France.’

‘Won’t that be an absolute triumph?’ asked Agathe, undaunted.

‘A triumph as you say, yes, but Pillai will be risking his life, contemplating such folly.’

‘So, Pillai, isn’t prepared to risk his neck to please his Agathe?’ The Chef demurred.

‘If you can’t do it, that’s all right,’ she said, ‘I know someone else who would not hesitate.’

‘Did anyone hear Pillai say that he was not going to do it?’ He addressed an invisible audience dramatically, raising his hand up in the air. ‘I just said that I am risking my neck, but for you, dearest, but that’s a small price to pay.’

It was thus that Midala found himself on board Le Quimper smuggled with the provisions for the voyage.

Pillai explained to Midala that he would be safe in the store room, to which he was the only one who had access, as it was known as a prime target for larcenous and greedy seamen.

When the warship left the port, Midala was not sure if it was real, or if he had died and was on the way to meet the Great Spirit. Either way it was good, for if he had died, he would surely meet Rolena and his dead children, if they too had died. If they had not died, then the Great Spirit be blessed, for He was looking after them. If he had not in fact died, he was the luckiest man alive, as having survived incredible hardships, he was now going home to meet his beloved little ones again. He was afraid of nothing, not of the arduous trek overland to Inhambane, not of storms or disease, perhaps a few nightmares, they were inevitable even to the bravest soldier, but they were nothing compared to the living nightmares that he had endured.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Matteo Fini

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Matteo Fini

Magnetite will now take a two week break. We’ll return on Friday 29th July with the further adventures of Rob Rob - will he be reunited with his darling Kitty?