Raju was not sure where he stood with Sukhdeo, and as Jayant was going to Calcutta by boat, he told Shanti that the only way of earning some money would be to go to the big city with his young friend and try to find work there. Shri Mahendranath had told him that with the new developments the East India Company was spearheading, work was easy to find. And you could sleep in my yard if you like, the man from Gujarat had offered. When it rains you can use a little shed I keep wood in, he had said, you are like a son to me, he had added.

Raju was doing quite well in Calcutta, fetching and carrying, but his mind was made up. He was going to get on that boat to.. he kept forgetting the name of that place… wherever… as long as it was far from the place where he had suffered such stinging humiliation. One day his Gujarati friend informed him that the Startled Fawn, which had been undergoing repairs in the dry dock was soon going to be ready to set sail, and he went to Roshankali to get the family.

Jayant had also been preparing himself, and soon the time came for the family to leave. The children were greatly excited by what to them was a big adventure. Jayant had carried out some repairs to his boat, in the hope that when they had got to the city, he might be able to sell it, and get to Mauritius with some cash in his pocket. They all convinced themselves that they would not miss the old life. They had few friends and Roshankhali had always been a struggle. It was so easy to minimise the good times they had spent there. Now they all remembered the unhappy occasions, the tragic deaths, in the case of Jayant, of both his parents in the cyclone. Raju spoke of Baba’s cruel end at the fangs of Dakshin Rai, of the hakeem’s long painful death. Shanti remembered with bitterness how her parents had gone from riches to rags through no fault of their own, and finally had to go back to miserable Gaya, a place where her Pitaji had said, people only went to die. No one was sorry to be leaving this god-forsaken place.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Sayamindu Dasgupta

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Sayamindu Dasgupta

They carried their possessions on their heads to the little pier on the Matla which Jayant’s father had built, and where they used to moor the craft. It was a small cockpit of a boat which could be propelled by means of two oars fastened on rowlocks on either side. It was hardly big enough for the three adults and two children it was going to ferry over such a long distance, with their meagre belongings. Jayant was an expert and could move the boat at speed with one hand, with his eyes closed and standing on his head, Raju said. He was not in the same class, but was certain that in a day or two, he would be just as good, as they were going to take turns. Jayant had said that manoeuvering along the channels could be tricky, with currents changing their minds just when you had acquired a good rhythm. But there were straightforward stretches which Raju could well handle. In the event, even Shanti did some rowing, as did the children, although their contribution was more a licence to squabble.

They left Roshankhali with the aim of linking up with the Hoogli and headed for Patharparma, a tricky start indeed, but Jayant kept the craft going steadily and at a good pace, and they reached there in mid-afternoon. The children to whom Raju had boasted of his friend’s skill kept pestering the boatman to stand on his head and row with one arm. They stopped at Patharparma, found a nice peepul to sit under and Shanti heated up the meals she had been preparing for a whole week before, and they had a feast. Sundari and Pradeep loved the place, its calm and its lush vegetation and would have liked to stay there much longer, but Jayant suggested that it might be possible to reach Sagar before sunset. The currents proved tricky and against expectation, the kids, instead of panicking found the pitching and tossing of the boat greatly invigorating. They managed to reach Sagar just as the sun was setting.

They slept under a keora tree after Jayant and Raju lit a fire to keep away tigers, for Jayant said that he had often seen tigers on the islands nearby, but said that as these beasts were great swimmers they could put in an appearance anytime. The little ones were very excited and said they wished they could always live like this, it was so much more fun. If only they could see a couple of tigers! They refused to go to sleep, and had to be coaxed. Raju woke up with the dawn chorus, aching all over, but the aroma of rotis which the tireless Shanti, having prepared the dough before leaving, was cooking over on an open fire, holding the rounded flour discs with her fingers, gave him new vigour.

‘Rani,’ he told her grandiloquently, ‘when we have grandchildren, I will take them on my knees and tell them about our trip down the river and the smell of those heavenly rotis you were making,’ adding after a short pause and closing his eyes, ‘the aroma will live forever in my memory.’

The children could not wake up and had to be shaken, but the mood of the day before had not faded in the least, and their merriment was contagious. It was all laughter and hope. Raju’s hands and shoulder muscles were aching from the previous day’s rowing, but in his experience, working on tired and aching limbs often made them better. Shanti must have been tired too, but as she did not complain, Raju thought that it would be unmanly of him to start moaning. Jayant said that they had every chance of reaching the Sangam where the Hoogli took the Damodar as its wife, and together proceed towards the Bay of Bengal. They had the choice of stopping, either at Geonkhali or at Nurpur, and they could easily reach either before sunset. They planned a stop for a rest and food at Kulpi.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 Eelffica

Photo Credit:

CC-0 Eelffica

Everybody was excited when what appeared to be a crocodile was spotted by the girl on the river bank near Belkupur, but they could never be sure if it was indeed one. It’s an old dead tree, said Jayant. What a spoilsport, thought the girl. However this did not stop Pradeep seeing crocodiles every fifteen minutes, whenever there was some unusual object that he did not recognise, some distance away. They reached Kulpi in good time, and had another long rest, and reached Geonkhali at the Sangam just as the sun was beginning to set. They marvelled at the serenity of the encounter, anybody would have supposed that the two branches would be lashing at each other in fury, like angry spouses fighting, but they behaved like a contented couple sleeping in each other’s arms after a night of passion. They slept soundly at Geonkhali, rocked by the gentle chant of the rivers flowing.

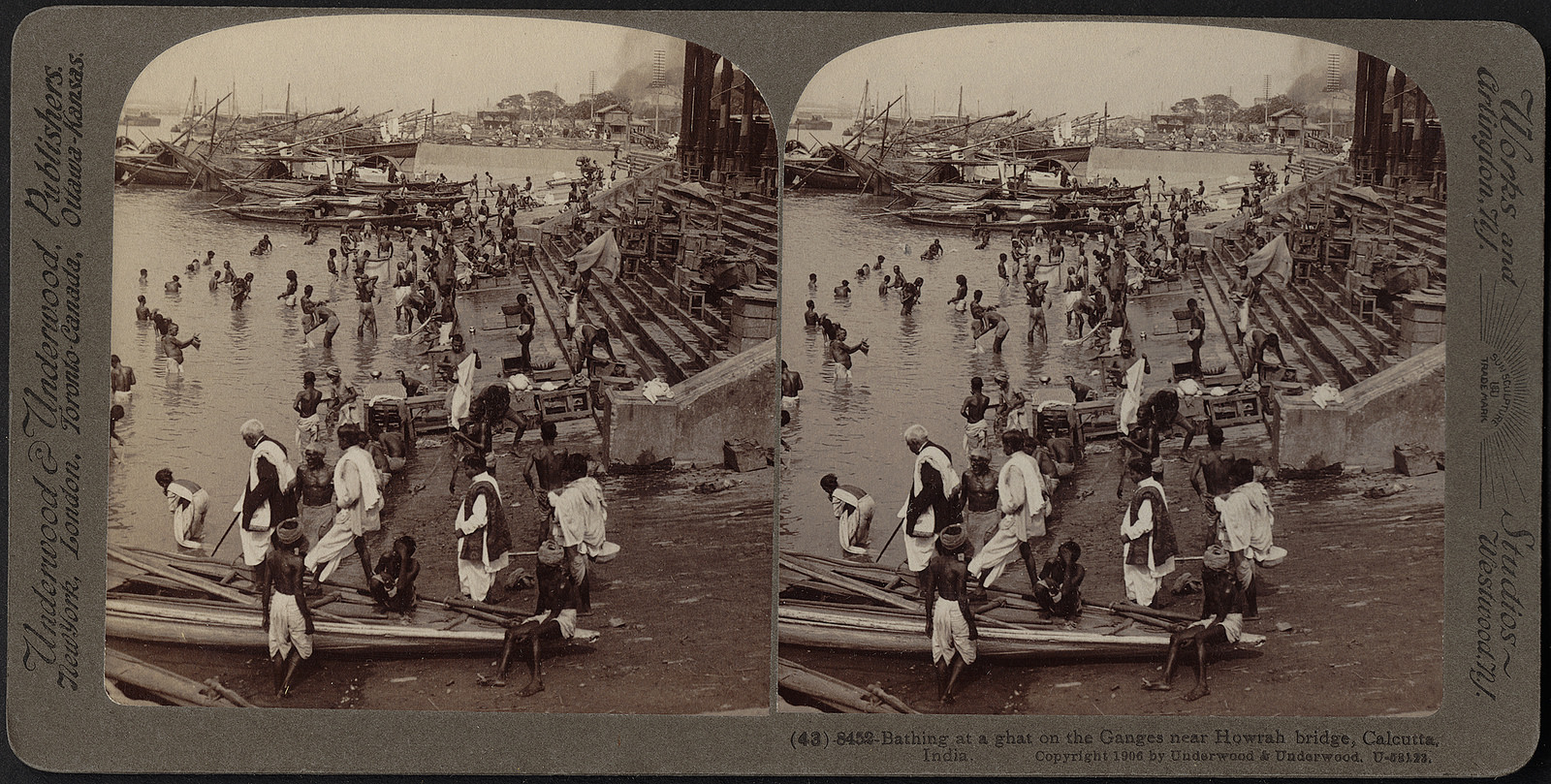

The rest of the trip was mercifully uneventful, and they reached Baj Baj in the afternoon, and Calcutta the next day. The crowd milling about all over the place confused Shanti who did not even guess that there were so many people in Bengal. The place was littered with sprawling children of all ages, in rags, playing or running about aimlessly, but engaged in some ill-defined games, many laughing as mucus dripped from their noses, some crying unconvincingly as they felt abandoned by older siblings. The family sat under a banyan tree by the river with their belongings at their feet whilst Raju went to see his Gujarati friend, and Jayant set out to enquire among the boatmen plying their trade in the Hoogli river if they knew of anybody interested in buying a sound little craft.

Shanti and the kids were to wait for the men next to a Ghat with a number of banyan trees next to it, where more little children were jumping about in the water and running after each other, pushing and jostling lustily. On either side of them, as far as the eye could see, there were sheds and go-downs, harbour offices, lining up along the bank, most of them with corrugated iron roofs glaring in the sun, containing produce that the East India Company had stored before shipping them to Liverpool or London, tea and spices, cotton, wood, jute, raw cotton, animal skins and a large number of other produce. There were pontoons at regular intervals on the river, linking the two banks, with impatient crowds, bales finely balanced on their heads crossing in either direction paying no attention to each other. A large number of ships could be seen beyond the mouth of the river anchored in the open sea. Access to and from them was only possible by launches manned by skilful and powerful betel chewing Cokhan boatmen with massive oars.

The noise and bustle were nothing any of them had experienced before. Although people did not seem to be talking all that loudly, as the several thousands voices of all sorts mixed, a considerable drone resulted which Shanti found overpowering. The children were fascinated by magicians doing incredible tricks, some swallowing fire, others throwing things up in the air which never fell back to earth and simply disappeared. Yet more laughing children were running about, playing gooli or racing or standing on their heads or doing cartwheels. There were all sorts of folks there, snake charmers playing their flute and getting the cobras to dance to their tune, one-eyed beggars leading blind fellow beggars, there were hawkers hawking everything from miracle drugs to half cigarettes, singers singing ghazals and birhas, preachers preaching, there were people with no legs propelling themselves with their arms, one-legged acrobats, pickpockets, fortune tellers, and there was even a three-legged donkey walking in the most comical fashion. Mostly the people were in rags, but all the colours of the rainbow could be seen on the crowd going about on their business, whatever that may have been. There were people eating, drinking, laughing, crying, there were people quarrelling, people sleeping, and if one looked closely enough, one could see people who had hardly bothered to take shelter behind a tree, emptying bladder and bowel, unmindful of the crowd.

Shanti just sat there, fighting the mounting irritation arising from the heat, the humming and the apprehension of the unknown, and tried hard to shut herself from the noise around, moving the two little leeches away from her when one part of her body became too hot and began to itch. The crowd around her became a haze, and she was barely aware of the odours around. Every single smell imaginable was present, the most persistent being sweat. Every now and then a sudden gust of breeze wafted in a stench of urine and excrement but there was also an earthy smell like when it has rained and the earth was drying, although in fact it was quite dry. There were groups of people cooking or frying all over the place, and this provided a smell of smoke and frying which was not unpleasant, but suddenly some people started burning dried chillies in an attempt to placate bad spirits. This produced a stringent unpleasant smell which went straight to one’s throat, causing the kids to start coughing. But she understood that most people around were probably also embarking on some momentous journey, and therefore were leaving nothing to chance. There was so much malevolence in this world. Angrily she pushed away Pradeep who was pulling her sari.

Raju had left some money with her so she could get some tea and puris for herself and the kids. She was terribly scared, of the people rushing in all directions, of the kids wandering away and getting lost in the crowd, of Raju getting robbed or beaten, or whatever. She tied the hands of the kids with the ends of her sari whenever she had to move. Fortunately there were vendors coming over every five minutes, offering to sell chai, nimbu pani, falooda, pakoras and puris and such things. The children wanted to do a wee wee every ten minutes, so she had to let them go the short distance towards a banyan tree with its hanging roots providing some sort of screen. They did not really want to ease themselves, they had discovered that the short walk was a sound strategy against being confined to a small area centred round their mother. When she herself needed to go, she thought that the best thing would be to tie the children to their bundles, but there was a family squatting nearby, probably also waiting for someone or something, and the auntie offered to look after the children and their things. Gratefully she accepted and disappeared behind a thick root, but she was immediately seized by panic. Were these people as honest as they appeared to be? Maybe that was how they made a living, they sat next to people who had arrived from another place with their things, offered to look after them and their children, and then the moment the adult was out of sight, they stole the children or the possessions, or both. But she bent forward and peeped, and saw the woman talking to the girl. She was relieved when she went back and found everything as they were when she had left. She began talking to the family. Indeed, it was as she had guessed, they were also Biharis and were also thinking of going to some other country, although the woman had no idea where. Ask their father, she said. Mareeshush? Shanti asked. No, she thought it sounded like Damrara. She was getting impatient when the men did not come back, and the heat was becoming unbearable. A sadhu, approached her and asked if he could pray for her and her family, and she agreed, and gave the man one pise which he gratefully accepted. I will tell you your future, the holy man said. ‘You have had a tough time in the past, but now everything is going to change for the better, you have a great future ahead of you. You and your family are moving to a new place, tell me if I am right.’ Shanti nodded. You will prosper there, he said, and you and your husband will live a very happy and fulfilled life. You will have three more babies and all will live, and become very successful in life. Shanti was not sure whether to believe him or not, but liked what she heard, specially as she was quite terrified of what was in store for her and her family. She parted with another pise. She forgot her annoyance at the men’s continued absence for a while, she knew that Raju was not one of those irresponsible men who forget their family once away from them. Maybe he liked a drink or two, but he never went overboard, and never got drunk.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Babak Fakhamzadeh

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Babak Fakhamzadeh

It was quite late when Jayant came back with the good news that he had easily sold the boat, and had been had paid half in cash and half in cloth and blankets. He was such a kind soul, most of the cloth was for the kids. But why did you not get any for yourself? Shanti asked. No, didi, he said, the children get dressed, and I feel the pride. And he had this endearing habit of smiling, closing his eyes slightly and moving his heads from left to right a few times before he spoke. Raju too reappeared, beaming all over. Shanti grabbed him and burst into tears, as her nerves were all frayed with the excitement and terrors of the day. ‘You took your time, never worrying about us,’ she said. Raju who had in fact been as quick as he could, knew that there was no point trying to defend himself and just smiled apologetically.

A hawker appeared and Raju bought tea and aloo pakoras for everybody, but Jayant insisted on paying saying that he had sold the boat for much more than he hoped for. Those Bengalis who think they are so clever are so easy to fool, he cackled under his breath. They sat down and had a little feast. The children who had allowed boredom and bad temper to get the better of their recent joyous state, soon regained their good humour and they all felt considerably cheered when Raju told them that Mahendra had arranged for them to travel in two, maybe three days’ time. They found a much more secluded place and the men made a sort of shelter with sheets and blankets to keep the punishing sun at bay. Raju and Jayant spent the day smoking bidis, sometimes enjoying some toddy. The Guajrati man had explained to Raju what the procedures were. First one had to go to the Auxiliary Harbour Office next to the Ghat, a hastily constructed shed with corrugated iron roofs which made it unbearably hot, tell the officer your name and particulars, which he will write in a book, put your thumb mark on some official papers, and then you get taken to a barge which takes you to the ship anchored further away down the Hoogli, where it was deep enough and where there was a port.

They made their way towards the Ghat and waited there for a crucial announcement. They found a huge crowd, for there were three ships leaving in the next three days. Just remember your ship is the Startled Fawn, Mahendra had said. No one really knew where the tail of queue was, so what people did was to push their luck, choosing a place where there was an almost imperceptible gap and literally burrowing in. Often people would moan and protest, and then if they were bigger than you, you said sorry and moved on, otherwise, you browbeat them and stayed put. Raju was unable to find a suitable place near the Office, so the family (and Jayant) settled down in a spot which was at some distance from the shed. Someone said the officers were now dealing with people travelling on the Jupiter which was going to Fiji and that it would take anything up to eighteen hours. A man asked when they were going to process the passengers of the Sea Pride, and a Bengali clerk said tomorrow noon. Clearly the Startled Fawn was going to be some time. The moment one family went in, the people behind began pushing, squashing everybody else. Tempers were frayed and angry words were exchanged, but there were always one or two wiser heads who explained that the pushing and shoving were not going to compress the time. The time, one of them explained, was going to be the same, it’s the people who would become thinner by being squeezed. Well said, Chacha, someone said laughing, and temporary good humour was restored. Raju, judging by the length of the queue and the rate at which people went inside the office, guessed that as their ship was going to be the last one to leave, it would be late tomorrow night, or even day after before things started moving for them. In fact an officious man with twirling moustaches, in some sort of uniform, had said the same.

Some time in mid-morning, while everybody was drinking chai and eating roti, which Shanti had cooked under the banyan tree, they saw a man who reminded them of Sukhdeo. They all laughed, in the knowledge that they were now out of the cruel man’s reach, even if it was him.

But it was him! And he seemed to be in quite a state, sweating profusely. He gave out a big sigh of relief when he identified Raju and his family. He moved faster with a big smile on his face.

‘I am so relieved to see you my boy. If you only knew how many sleepless nights I have spent… I have been looking for you all over the place… Mahendra told me you would be queuing up near the Ghat.’

‘Namasté, uncle,’ Raju said coldly, wondering why the old pain-giver was so relieved to see him.

‘I have something of great importance to say to you, I wonder if you would like to come with me… somewhere where we can talk… privately.’

‘Get lost, you old bastard!’ Raju wished he could say, but he did not. Instead he said, ‘Oh Uncle, I am glad to see you too, but if you have come all the way just to get me to change my plans at this late hour to come back and work for you as before, I am afraid it is too late now.’

‘I know, I know, but no, I am afraid it’s more serious than that, just come along for a bit.’

‘As you can see, there is a massive big queue, I cannot lose my place —’

‘No, people will understand, your family is here, right?’

‘But the ship —’

‘Your ship isn’t leaving until the day after tomorrow. All I need is fifteen minutes, then you can come back here and depart with my blessing.’

‘But, but’

‘Just come, you will not regret it, I assure you, Shanti is well able to manage fifteen minutes without you.’

He looked at Shanti, and she shrugged, meaning do as you think fit and get rid of him as quickly as you can. Jayant gave him an encouraging look which meant, I am here, I’ll make sure no harm comes to the family, so he reluctantly agreed to walk a few steps with Sukhdeo.

‘I want to go with Baba,’ said the girl forcefully. Raju stopped in his tracks.

‘Bring the little jewel along,’ entreated Sukhdeo, ‘what’s the harm?’ Shanti demurred.

‘Pradeep will want to come too, you know what he’s like,’ she said.

‘No, I don’t,’ said the boy, ‘I want to stay with you here, Mama.’

‘Come along then, Sundari,’ said Raju extending a hand which the little girl immediately seized, and they were on their way.

‘Don’t let go of Baba’s hand whatever you do, Sweetie,’ were Shanti’s last words, and father and daughter and the leech walked away. She watched her man for a while, sure that he would turn round once, although usually, whenever he had said his goodbye, he seemed to forget the people and things he had left behind, so much did he hate lingering. Please Bhagwan, Shanti entreated silently, make him turn round just this once, and indeed, just when he was almost disappearing amongst the milling crowd, he turned round and as their eyes met, he gave his head a little twist to one side and winked at her. She was too far to see the winking, but knew her man’s gestures inside out. She craned her neck forward to make sure he caught a glimpse of her. My dear man, she thought, I just hope that Dukhdeo fellow means him no harm.

‘Sundari,’ said the old friendly woman sitting beside them, ‘what a lovely name!’

‘No, chachi, we just call her Sundari, it’s not her real name, her name is —’

‘She is so pretty, so she deserves that name,’ said the old auntie merrily.

The time passed very slowly. Rumours were rife and contradictory. One barge was leaving, it was with passengers travelling on the Jupiter. Shanti began panicking, but someone who looked quite authoritative explained that the barge that had left was coming back and going to do two or three more trips, and that in any case there were three barges plying between the Harbour Office and the port. The man also said that the Startled Fawn was not going to be ready until the next day. Shanti was greatly relieved to hear that, but still wished Raju would be back soon. Half an hour elapsed and Raju was not back. Suddenly Jayant became very excited.

‘Look, Raju Bhai is there, can you see him?’ And he pointed at the figures of a man of Raju’s appearance and a little girl at some distance away.

‘Are you sure it’s them?’ asked Shanti who was not convinced, ‘what colour was the dress of the little girl?’ Jayant had not noticed, but was so sure of what he saw that he tried to remember what the girl was wearing, and blurted out, ‘blue.’

‘She was wearing a green dress,’ Shanti snapped.

‘Might have been green, so difficult to say, in this light blue and green look so similar,’ adding almost shamefacedly, ‘also I have difficulty telling green from blue…’ But he decided to go find them and bring them back. However, when he started walking, he found that it was next to impossible to inch himself forward. People reacted angrily as he tried to squeeze past them, and that made progress very difficult, and in no time he was swamped by the crowd. As Shanti could no longer see him, she thought that the two men must have met by now. Damn that giver of pain! Hope nothing bad has happened to my Sundari. Why did she want to go with her dad? Fortunately for her, in the heat of the afternoon, she dozed off for she did not know how long, but when she woke up, Jayant had not come back. That Jayant is so unreliable, she thought.

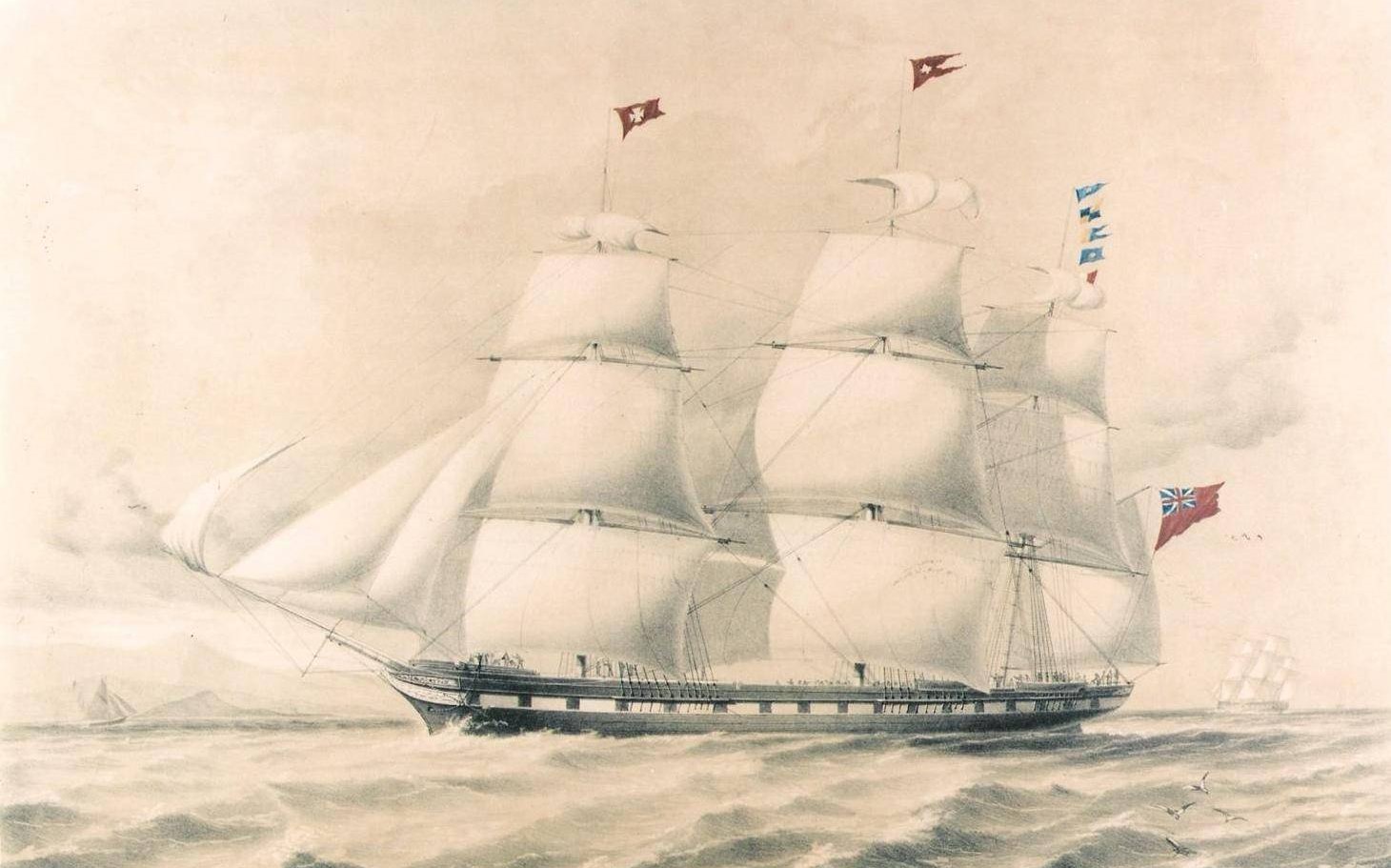

NB: The painting of the ship in this chapter is in fact of the RMS Tayleur, a full-rigged iron clipper chartered by the White Star Line, and built in Warrington, as was a ship named the SV Startled Fawn, built around the same time by Fletcher & Co (see wrecksite for more details). The Tayleur was sunk on its maiden voyage, hopefully the same fate will not befall our protagonists on the Startled Fawn.