Midala had slept not a wink all night. Shortly after the first crow of the cock, the tom toms had begun to rumble. This time things were happening nearer home, in Owambane, two days’ walk away. They told of how they were threatened and felt powerless against the force poised to attack, how those who did not flee into the bush and those who did not die resisting were captured and taken on the ship in fetters, and how their village was looted and burnt to the ground.

This time the Cojo seemed taken aback, but assured his people that he had everything under control. There was no need to worry, he said. An assurance which was was, like a talking drum: the hollower one was, the louder its sound. The warrior had no doubt that the Cojo ought to be doing something. The danger was real and imminent. Only a fool could fail to read the signals. Was the Cojo a fool? Could the Chief be considered a criminal, a traitor to his people, in his dereliction of duty? The Spirits had clearly wanted him to lead them and protect them, and he was selling them down the river. Would the Spirits forgive an honest man who had no axe to grind if he worked towards the elimination of a corrupt and useless Chief? For once he did not chase away the disturbing thoughts breaking the banks of his mental defences and flooding his conscious.

The people were famous for their optimistic disposition, as could be evidenced by their relaxed bearing, their jaunty walk which suggested that they were on the point of breaking into a dance, their ready smiles which brought comfort even to the gloomiest among them. They were a fun-loving people, much given to singing, dancing and music making. The heavenly sounds coming out of their timbila and their horns could produce the same effect as the brews they made from fermenting tangerines and cashew nuts. Now, with this calamity looming large, you never saw a smile on the lips of the folks, they walked with their heads bent down, and were forever looking behind their shoulders as if they feared someone was going to jump on them from behind. Everywhere Midala saw long faces, defeated looks, shaking heads, and hands flung up in the air in a gesture of helplessness. At his approach excited conversations turned into low whispers, and murmurs into nervous coughs, for nobody wanted the commander of their army to know how afraid they all were. From a distance he saw people arguing, and for once, he had the feeling that they were actually listening to each other, for the Chopis had the reputation of talking and laughing a lot, but of rarely listening.

Midala would have liked to send his wife and children into the bush for safety, but anybody leaving the village would have been seen as a traitor and dealt with accordingly. Whilst he was around to defend them, no harm would be done to them was what he promised. Disobedience was tantamount to treason. It was widely known that the Chief had spies everywhere, so when people talked they had to be ever so careful. There was a saying about trees having ears, and sending messages on their leaves carried by treacherous winds to the Cojo. Midala smiled as he remembered young Abo saying that he had spent hours looking at trees in order to discover where their ears might be, and had not found any.

At night, after the children were all asleep, Rolena pointed out to him that his forehead had become narrow with frowning, and he repeated that he was not worried, that the Spirits would look after them. I trust the Spirits, Rolena said, it’s the Cojo I do not trust. Then to her surprise he asked her whether she thought it would be a good idea for her and the little ones to run away, to the bush somewhere, until he could come and join them after. Her response was not unexpected. Angrily she asked him if he really believed that she would do this. No, my man I will stand and fight by your side. What about the children? he said simply. He whistled in admiration as she came up with her suggestion: Pack them on Bobo Big Ears, and he will take them to safety across the river. Indeed Abo could almost talk to that lovely beast. They did not take long to decide that the best solution was indeed to send the kids away to safety in Chokwé.

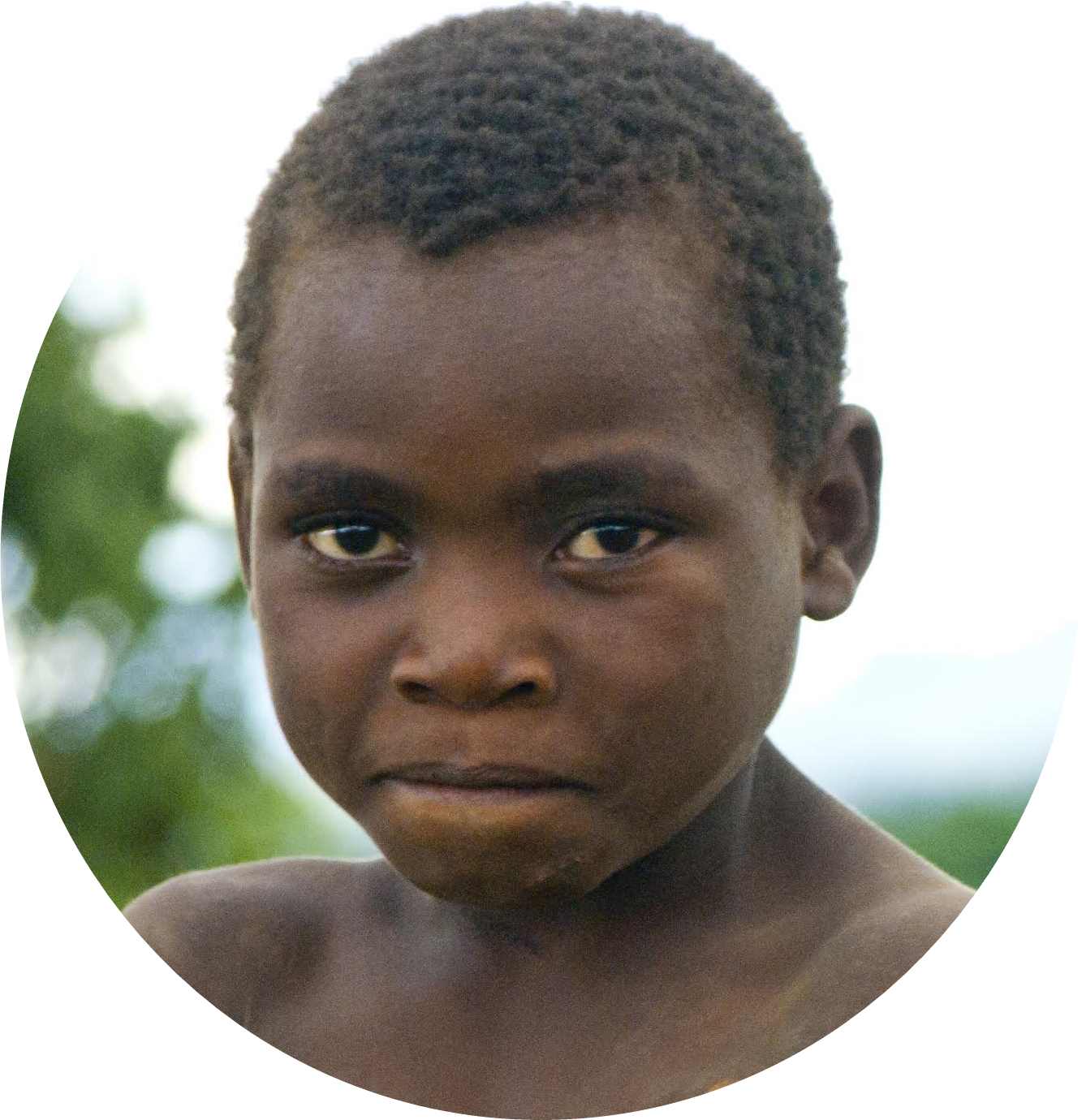

As it was full moon, he and his wife started preparing for their children’s flight straight away. They packed food and clothing, animal skins to be used as blankets, and water, and whilst Rolena woke the little ones, he went to get Bobo who usually retired into the hollow in a strangler fig tree for the night. Rolena told Abo that he was going to take the little ones to Chokwé on Bobo Big Ears, and he had to look after them for some time whilst they helped defeat the enemy, after which they would come for them. Midala read his son readily. On the one hand the boy was sad and slightly apprehensive, as he knew that he would miss his parents, but on the other hand, he was going to have a big responsibility, and this he relished. Midala explained that Bobo would take them to Chokwé by the river side and that the tribe there would welcome them when they told that they were Midala’s children. Without further ado, the children were on their way.

Photo Credit:

CC0 Andy Brunner

Photo Credit:

CC0 Andy Brunner

A few hours later, the tom-toms from the tribes across the river began to rumble again with unusual vigour and persistence, which probably meant that the slavers were getting nearer. It turned out that Mara Mara, the settlement just across the river had been burnt to the ground, to teach a lesson to others that resistance against their might was pointless. We tried to resist, but sticks and spears were no match against cannons, guns and treachery. It will be your turn next, the tom-toms warned, may the Spirits of the Ancestors give you strength so you can fight the enemy with greater success than your unfortunate neighbours. May you die spear in hand, brothers and sisters, for death is sweeter than subjugation!

Midala finally accepted what he had always known, that the Cojo had much to answer for. He, it was who had drunk from the same cup as the devil and had not bothered to turn the cup round first. Or maybe he was the devil! The warrior had served him loyally, because he was taught by his father that the Chief got his authority from the Spirits of the Ancestors. Suddenly he dismissed from his mind the notion that he had held sacred until now: that the Cojo was the descendant of a river god and had taken human shape in order to lead their tribe to greater glory.

He, who used to treat his subjects with singular lack of courtesy, always shouting at everybody and scowling, had a totally different behaviour towards the sinister slave traders. He was all bows and smiles with them and their men, of course sir, sure thing sir, whatever you say sir. He fed them like kings, offered them maidens to comfort their beds, and let them drink half the gin he had bought from them. Ibn Qalb who claimed to be a true believer of the koran would invariably laugh as he dipped a finger in his gourd and shake away one drop of the forbidden drink, saying, “A single drop of alcohol shall not cross your lips, O ye faithful… and there goes that drop.” But their allegiance was shallow. All concerned knew that the foreigners were friendly to the Chopis and their Cojo only when it suited them.

Another thing which sorely tested Midala’s loyalty was the Cojo’s dishonourable order to re-arrest liberated slaves, so they could be handed over to the slavers in order to make up the numbers. Midala and one or two of the braver councillors had pointed out that this was both illegal and immoral. The Cojo had shouted that he was the one who decided what was legal or moral. Who was the nephew of the River God? Midala or he the Cojo? Midala had executed the order, but had never been happy about it. He knew that he was not going to put up with the excesses of his chief much longer. The Spirits would understand that his action was motivated by honour. It seemed obvious to him that the Cojo had no plans to stop the fiendish Arab and his wicked English accomplice.

After the news of the overwhelming of Mara Mara, Midala, Nkilo and Mossane went to see the Cojo in the Palaver Room. He did not like people asking to see him. Usually he was the one asking to do the seeing, but these were the three most powerful men in the tribe, and he knew that he had to hear them. Mossane had offered to shoot the first arrow.

‘O Cojo, nephew of the River God, hear us.’

‘Speak, Mossane, brother of my first wife.’

‘We are sure our leader has plans to stop the attack—’

‘What attack? There’s not going to be an attack. The ships coming in belong to my friends, people I trade with, why are you afraid like a woman?’

‘But they attacked Owambane, Mara Mara,’ Nkilo said impatiently.

‘The Marzuk of Owambane is a fool, he was asking for it. Ibn Qalb and the white people respect us, they are our friends.’

‘We know that the Marzuk also believed the same thing,’ said Midala.

‘That Ibn Qalb and his white partners respect us and are our friends?’ laughed the Cojo, ‘he is right!’ It was only after he had said this that his audience joined in the laughter with a singular lack of enthusiasm.

‘My little joke,’ he explained, ‘yes, we have developed an understanding with the slave traders, and there is nothing like a little diplomacy to solve problems.’

Then suddenly he frowned and nodded at his three visitors.

‘Let us just suppose that you have a point, that there is some danger, what would you propose? Are we in a position to defend ourselves?’

‘It’s a bit late in the day, O Cojo, Nephew of the River God,’ said Midala.

‘You see!’ said the Cojo, happy to be vindicated.

‘We should have prepared for this weeks ago… they have guns and cannons, we have nothing.’

‘So, isn’t my way the best?’

‘Your way,’ shouted Mossane, trying to control his temper but failing to do so, ‘means certain death and capture for the tribe.’

‘Will you fight them with sticks and stones? Tell me.’ The Cojo was now quite angry, ‘There is no way of stopping them if they have made up their minds to destroy us,’ he said, adding after a short pause, ‘trust my powers of persuasion.’

There was a short silence, which Midala broke.

‘I have a plan,’ he said, ‘I cannot guarantee that it will work, but I believe that it is the only course of action left.’ The Cojo waved his hand at him dismissively, and turned his head away testily.

‘Midala is no fool, O Cojo,’ said Nkilo and Mossane in unison, ‘you must listen to the words of his mouth.’ The Cojo said nothing, but looked at the military man wearily. The latter took it as permission to hold forth.

‘We do not know how many attackers there will be, we have to plan for a force of one hundred. They are hardly likely to number more than that. With their guns, they do not even need that many. Although fully armed, they are seamen, not soldiers. We’ll get one hundred of our best men, proven in battle, and they are in good shape and condition since we fought our last war only a short time ago—’

‘Midala’s plan is a very good one, O Cojo!’ said Mossane enthusiastically.

‘Anybody coming to attack us must necessarily pass under the strangler fig tree.’ The Cojo seemed interested for the first time, and nodded thoughtfully.

‘Our men will be armed with spears, machetes and bows and arrows, and will be waiting on top of the strangler, hidden by the foliage.’

Photo Credit:

CC0 sandid

Photo Credit:

CC0 sandid

‘I see,’ said the Cojo merrily, ‘that’s damn very clever,’ he admitted, ‘then our men pounce on them from above, disarm them, seize their guns and we kill each and everyone of them.’

The four men laughed happily, as if the victory had already been won.

‘So you like my plan?’ asked the Cojo suddenly. The three wise men knew their Cojo, but were relieved that he was hijacking their plan, which meant that he was seeing reason for the first time.

‘But we need to train, practise the jump, we need to hone in our shooting skills, there’s such a lot to do.’

The Cojo suddenly jumped on his feet, and squealed with joy.

‘And when we have killed them, everything in their ships will belong to me! Their gin, their guns, their gold. We will live like white men!’

‘Yes, we will have their guns, so when their friends send a force to avenge their deaths, we will have the means of defending ourselves.’ said Nkilo.

‘I will make a big speech to the tribe and tell them that there is no cause for worry, that I have got everything in control.’

‘We must start preparing immediately,’ said Midala, ‘we cannot afford to waste time.’

The Cojo blanched on hearing this. He looked at Midala with his piercing eyes and wagged a finger at him.

‘Your father never dared talk to me like this! Are you suggesting that listening to my speech is a waste of time?’ he asked.

‘No, of course not, O Cojo, nephew of the River God, but they will be here tomorrow, and we—’

‘They won’t be here for another three days,’ said the Cojo decisively.

‘But O most exalted Cojo, how do you know?’

‘My fortune teller said so. He said that the ships would be becalmed for three days, the Spirits of the Ancestors have been appeased, so don’t worry, you’ll have all the time in the world to practise.’

‘Your fortune-teller? That man is a fraud,’ said Midala.

‘When he predicted floods, we had a drought,’ said Mossane.

‘When he said your new wife was going to have a son, you had twin girls,’ said Nkilo.

‘When I order silence, I get silence!’ screamed the Nephew of the River God. ‘I have been kind enough to listen to you, I have granted you leave to bad-mouth my friends… against my better judgement, but I order you all to come to listen to my speech! Then you can put my plan in action.’

‘But Lord Cojo,’ Midala had protested, ‘what if—’ The Cojo stopped himself flying into another fit of rage.

‘I will not hear another word! Just come to the strangler tree before the sun disappears behind the Meira Hills.’

Now, the three would-be saviours of the tribe were condemned to a fate worse than death: listening to the Cojo’s speech. It was a secret to nobody that the three things the Cojo loved above everything, were, and in that order, himself, flattery, and speechmaking. It must be said that he had a great booming voice and spoke in pleasant rhythms. He loved to use beautiful, nice-sounding words, the meaning of which most people, including himself often did not know. Obviously, to him, words meant whatever he wanted them to mean.