The Chopi people had always had a unique relationship with elephants whom they called their forest cousins. The elders told of how their first ancestor suddenly appeared in the forests of Inhambane amidst a herd of elephants and started the Chopi tribe. Midala even had his own elephant, Bobo Big Ears, and he took great pride in the fact that his little boy Abo could handle the big beast with the same ease as the tribe’s champion rowers their canoes. They were the husbands of all the teams from Mambone to Inharrime. Even as a toddler, the boy had never been afraid of the big beast, laughing his head off when one day, Bobo suddenly wrapped his trunk around him, raised him high up in the air and gently rocked him from left to right, to the consternation of his mother. It was as if the boy and the big-eared beast could read each other’s minds. Abo assured Midala that Bobo not only understood Chopi, but also spoke it. Doting father that he was, he had only smiled condescendingly, and this had upset the son who hated being disbelieved. ‘I know you don’t believe me, but it’s true,’ he had said indignantly.

‘Well, Abo, sweetie, the day I hear you two talk I will believe you, I promise,’ the warrior had said, making an effort not to laugh. The little boy was not easily pacified.

‘But my father, how can you hear him talk to me? He only talks to me in my sleep.’

If Bobo was almost family, the rogue elephants which ran amok over everything, demolishing huts and fences, devouring crops, were an altogether different matter. Sometimes they even trampled unwary people to death.

Elephant patrols had been in existence ever since man came into contact with their big cousins. Their hunger drove them to seek sustenance wherever they could and they trampled over crops rendering them useless. Thus all able-bodied men and some of the more daring women began guarding the plantations at night, armed with spears and torches. At the approach of the crop raiders, they would holler at the top of their voices, and brandish the flames in order to frighten the attackers, but it took more than noise to stop the fearless pachyderms, fuelled by their great hunger. Spears and arrows had little effect, and it was agreed that there was little anyone could do against this calamity. It was like stopping huts leaking during the harmattan. Or smoke rising. Sadly, many valiant people were trampled to death for not much.

Midala was not only the commander of the Cojo’s warriors, but he also had the reputation of being the brainiest man around, invariably finding solutions to the tribe’s problems. He was the one who had thought of using chillies to which the big beasts were averse. He asked everybody to plant the pungent plant around their crops of maize, okra, cassava or tomatoes, and this had indeed kept the famished beasts at bay, if only for a short time. Elephants, however, are resourceful and clever, for weren’t they related to the Chopis after all? It was not long, as Midala had anticipated, before they had learnt to uproot the chillies, discard them and then trample and devour the defenceless crops.

For weeks Midala had used all his mental resources to find another solution, and after spending many sleepless hours in deep thought, he had come up with a modified system which he was now ready to put to the test. The crops had flourished and the big-eared beasts had been seen inching towards the plantations. Midala was going to act.

He had instructed people to weave thick ropes from sisal plants which grew in abundance on the slopes of the hills surrounding the village and had despatched the near redundant Elephant Patrol, augmented by an ever-willing army of kids who usually hampered more than helped into the forest. Their mission was to collect as much dung as they could find. When the destructive cousins were getting ready for a raid, they drew nearer and nearer to the settlements providing dung aplenty, and this, ironically was now going to be used against them. We fight them with sticks, we fight them with stones and now we’re gonna fight them with their own shit, the people said merrily.

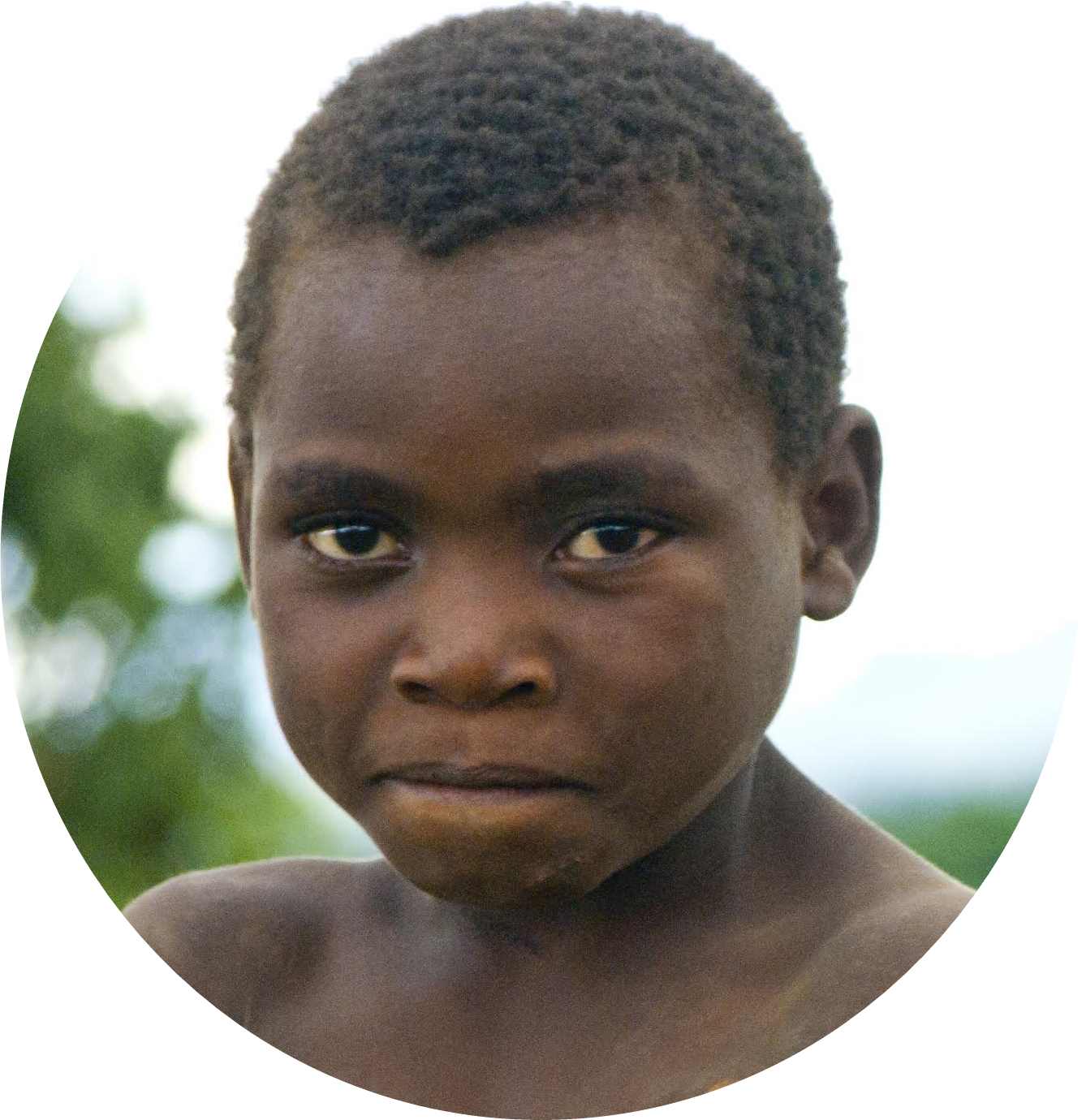

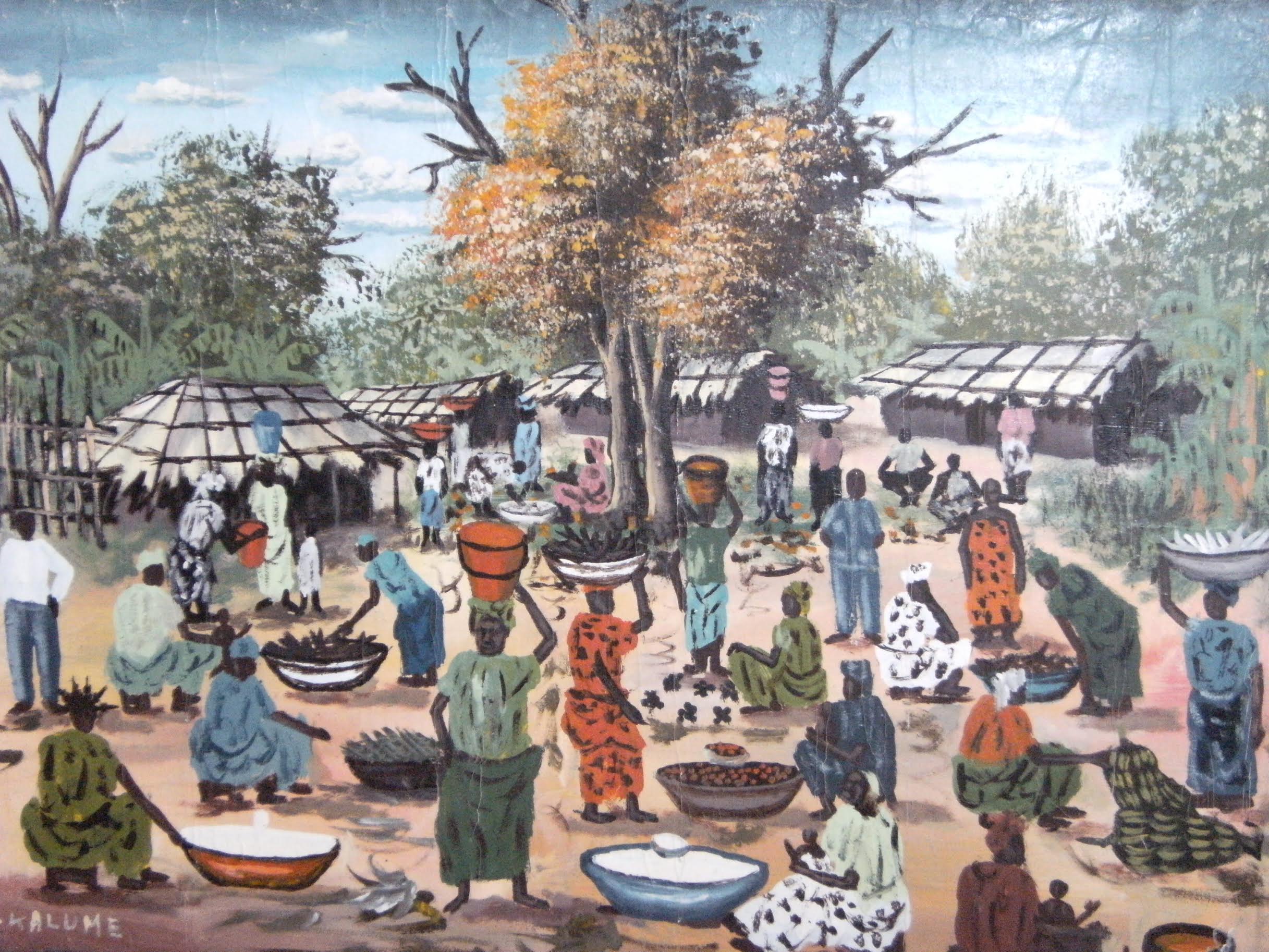

Photo Credit:

Kalume (painting owned by the author)

Photo Credit:

Kalume (painting owned by the author)

In the morning all able-bodied men and women had been asked to assemble in the fields around the strangler fig. Kids did not have to be dragooned in, they just turned up, to help prepare for the final and decisive combat. Midala had been on his feet since the roosters had begun to crow, preparing the ground and giving out instructions. The women prepared the mixture of dung, game fat and crushed chillies mixed with ash and straw, and then the men wrapped this mix all along the ropes, held by older children, like one does the skewer with meat before roasting.

The application of the paste was a delicate operation, for often, no sooner had a fair length of the rope been primed than a previously done length would see its wrapping plop to the ground. Midala thought that he really should work on finding a way of getting the paste to stick. Perhaps he should experiment with different amounts of ash.

With the new system now ready for inauguration, there was no need for an elephant patrol the size of an army. Goja, the palm-wine tapper who claimed he never slept a wink at night had volunteered to stand guard with Midala. Abo begged to go with him, swearing that he would not go to sleep on his legs as Rolena, his mother, claimed he would. Midala remembered how excited he had been when his own father had taken him night hunting for the first time, and pleaded with his wife to let the boy have his wish for once. He understood that the history of the village was in the making that night and wanted his son to be part of it. That was how the traditions and histories of the tribe were transmitted from generation to generation.

The ropes were placed around the field, suspended at regular intervals by posts fixed to the ground or to trees. Together, father and son, and the self-proclaimed insomniac waited, although the latter leaning against a tree was soon snoring blissfully. It was not long before they heard a distant rumble. Clearly the elephants were on the march and their stampede was gathering speed. With the help of Abo, Midala lit the ropes one by one, with torches. A pungent smell immediately filled the air, but by sheer will-power the boy kept his cough in. Unfortunately the wind was blowing in the wrong direction, and the raiders were protected from the irritating stench rising and floating away in the opposite direction, and kept approaching. Would all the work the tribe had put in produce any result? The rumble grew louder. Father and son held their breaths, and to their dismay the shapes of the beasts began appearing in the moonlight, growing bigger and more threatening by the second. Suddenly, what must have been the leader of the herd stopped and gave out an angry growl. Thankfully the wind had changed direction at the right time. The whole herd began groaning and ground to a standstill, and to Abo’s delight, they turned round and with howls of despair, they ambled away, defeated. Midala felt the grip of his boy’s hand on his grow tighter, and never would he be prouder of his son. Never again would the raiders pose such a threat to the tribe. Now that they had a system, he would modify and improve things all the time. Goja suddenly woke up and jumping in the air shouting merrily, we did it, we did it!

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-SA Ed Yourdon

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-SA Ed Yourdon

No sooner had the tribe neutralised the danger from their rampaging cousins, than the tom-toms began rumbling one morning. The message originated from Massingwé and was being successively relayed by tribes living near Morrumbene, Pembe, and then Maxixe until they reached Mambocké. Most people had understood the broad thrust of what was happening. Ships had been sighted by the folks of Massingwé, heading towards their lands, and it was not good news.

This was a complete surprise to the tribe. The Cojo who was supposed to be the protector and chief of the tribe was known to be in league with the slave-traders, and he quite shamelessly sold his own people to them. For baubles, fire-water, and hats. He had a predilection for gaudy headware. This time, it was clear that he had not been informed of the impending visit from his so-called friends, Sheikh Yahaya Ibn Qalb and Captain Flyte-Camilton. As a rule he was warned of their visit in good time, to enable him to assemble the number of slaves required by his associates. When the captives brought home from the wars were not enough, he fulfilled his quota by putting the tribe under all sorts of pressure that Midala, the military commander did not approve of. He started by taking treacherous measures, getting his corrupt courts to send minor miscreants to the escape-proof clay pit from which they could more easily be sold to his two partners. The sinister Zanzibari and his equally hateful English partner in crime could manipulate the Cojo, who always loudly proclaimed that he was appointed by the Great Spirit to protect and guide his people. As if the admirable masata the tribe had elaborated over centuries, from cashew nuts and tangerines were not good enough, the Cojo had become addicted to English fire water. The moment the visitors dangled a bottle of gin in front of him, he became weak in the knees, like a hunter coming home after a week in the forest, stalking some game, approaching the bed of his favourite wife at full moon. They could mould him in any shape they wished, like the best potters in the tribe, their clay.

Midala was torn between his military duty and his conscience, his oath to obey his Chief blindly at all times conflicting with his view of what was right and wrong. Responsible for his fighters, he had to keep to himself his qualms about the senseless ventures the Cojo embarked upon. The Spirits who had appointed the Chief must surely have their reasons, although these eluded Midala. Fortunately he had Rolena, and she was a wise woman. To her he would reveal all his reservations, but he had not approved of her suggestion that he ought to work towards the elimination of the Cojo with like-minded elders. He could never contemplate or condone treason. He was himself the son of a warrior who had taught him everything he knew about obedience, to the Spirits, to the Chief, to his people. His life was at their disposal. He had once believed with all the fibres in his body that the Cojo’s person was sacrosanct, but the seed of doubt sown in his mind by his wife over the years had sprouted, and was thriving with the waters and fertilisers from his own conscience. Which is why he was so full of torment, why his jaws were never relaxed, why he never had a full night’s sleep, why he no longer laughed as heartily as his erstwhile cheerful nature dictated.

It was clear to any thinking man of the tribe that the Cojo was in thrall to the slave traders. He seemed unaware that the foreigners were cheating him, with their glass beads and hats, their colourful textiles and their gin. Midala, as military chief had often asked for guns and ammunition, to be used in the many wars the Cojo initiated, but the sinister pair kept promising them for the next time, and failed to deliver, no doubt determined to keep the tribe weak. Over the years they had brought a handful of guns with very little ammunition, and these were defective and seemed to be a greater danger to the user than to an enemy.

He no longer relished fighting the Cojo’s wars when he did not understand their necessity. Military man though he was, after the many senseless killings that he had been party to, he had turned into a man of peace, believing in negotiation and thinking it much more satisfying to ensure that his fellow tribesmen had plenty to eat, to win wrestling and regatta competitions with the neighbouring tribes than to be constantly fighting and killing them. Unfortunately his allegiance had to be to the paramount chief and his duty to fight his enemies, arrest criminals, and carry out whatever task the Cojo wanted done. As he was no yes-man, he was never in the inner circle of the Cojo and his advice on policy was rarely sought. The chief only listened to his own coterie of toadies.

The Cojo usually gave him his orders, which he would carry out without questioning, for that had always been the tradition of fighting men. That was what his father had taught him. The Cojo wanted a war with the Hopparis. He was a soldier, he owed the Hopparis nothing. He prepared his army in the best way he knew, planned his strategy, and attacked the enemy. Until now, the Spirits be praised, they had always seen to it that his men came out victorious. Our boys need wives, go kidnap some women from the Jaba tribe, the Cojo would order. Midala would set out with his commandos and come back within a week with reluctant brides for his fellow villagers as well as captives who could provide labour, and again be sold as slaves. Until now, he rarely questioned the rights or wrongs of the matter. His belief was that if the Spirits did not approve, they would be roundly defeated. Would the Spirits favour the wicked against the good? Besides what would happen if everybody questioned the orders of the leader? He imagined how difficult it was to keep a tribe going smoothly. Discipline was of the essence, for without it, anarchy and chaos would end up clogging the system, like weeds strangling the crops, if they were not exterminated the moment they emerged from the soil.

The council of elders who was appointed to judge those accused of theft, of causing grievous bodily harms, of murder or rape, were noticeably readier to pronounce the guilty verdict on little or no evidence whenever Ibn Qalb or Flyte-Camilton were due for a visit. One more slave meant one more bottle of English gin.

The men on the ships had an insatiable demand for slaves, and he knew that the arrangement with the Cojo notwithstanding, if the latter could not deliver, they would not think twice about forcing their way in and taking what they needed. They had guns against which spears and arrows could do little. Rolena had seemed shocked by what she heard. The man must be stopped, she said. I think you should throw a big rock in front of his canoe. Was this really high treason or common sense? A mortal sin in the eyes of the Spirits or a selfless act in the defence of the tribe?

‘Father,’ Abo asked him in the morning, ‘what are those monsters from the sea that everybody is talking about?’

‘Monsters?’

‘Everybody talks of slavos, coming to capture and kill us. I saw them, they were giant monsters dribbling slime form all over their slimy green bodies.’

‘You saw them? Where?’

‘In my sleep my father, but I was not frightened.’

‘No, they are human, and it’s slavers, not slavos, but don’t worry. Daddy and his army will stop them, trust me.’ He knew that it was an empty promise. He did not usually indulge in that, but what does one tell an apprehensive child? He wondered whether his duty towards his children outweighed his duty towards the Spirits.