Chapter 15: Dunrobin

(Dunrobin, Scotland, Early 1812)

On that cold spring afternoon, with scattered snow still covering the tops of ridges, Sir John Sinclair sat in his coach dressed in his finest, feeling that he had at last made it. Chief Guest to dinner at Dunrobin! He had met the Duke briefly when he was Marquess of Stafford, had curtsied to him and received a nod of approval which had gladdened his heart so much that he had been unable to sleep that night, repeatedly recounting to Lady Sarah every detail which he could remember. This was surprising indeed, in view of his own pedigree and superior intellect, but he had yearned for the day when he would meet the legendary Elizabeth Gordon, who had become Duchess of Sutherland at the age of one, and later Duchess of Stafford — surely her blood must be as blue as my specially tailored blue velvet cape, he had thought. Lady Sarah had been aggrieved when it was made clear that the invitation did not include her, that this was not strictly speaking a social occasion. The noble couple had made it plain to him that they wanted to hear his views on the Improvement. He had explained that as surely as Loch Brora thawed in spring, the time would come when she would be presented to the Duchess and eat at her table, for after all they were themselves nobility, albeit of the minor variety, he having only been born in Thurso Castle and a descendant of the obscure Duke of Lauderdale. Obviously they did not invite comparison with the Staffords and Sutherlands, but John was aware of his sound intellectual worth and calibre. He was recognised as one of the finest brains of his age, having been a brilliant scholar at Oxford. His tutors, had included Adam Smith, whose thoughts on the free market he had espoused with singular enthusiasm. He deeply held the view that the more money the rich make the more they can help ease the burden of the poor, who, self-evidently had no talent for making money themselves. The eminent Father of Economics had further predicted an extraordinary future for him. Which is no doubt why the good Duchess Duchess had invited him.

He ordered the coachman to speed up. It’s much better that we arrive half an hour early, Rabbie, he had explained, when we can wait outside the castle and take in its splendour, than be even half a minute late. He took out his gold watch from his waistcoat pocket and was satisfied that they would indeed get to Dunrobin in good time.

The Improvement! That was what was going to bring untold wealth to our part of the world, he had thought. Nowhere in the world were the rights of proprietors so well defined and protected, and he exulted in this. Which was what motivated his clarion call, “Colonise at Home!” He rehearsed his views in his head, picked words and sentences which he felt were going to impress the noble pair. He was a deeply religious man and would never do anything to harm a fellow Christian, but can those slothful Highlanders, given to illicit distillery, poaching and swearing — and no doubt worse — be called Christians? If God in his wisdom made eggs, it was because he wished us to enjoy the savour of the omelette, but the first step is to break the eggs. So, yes, some folks are going to suffer initially, but the end result is going to make it worth all the pain and sacrifice. Yes, he would expound his views and the country would thank him for the benefits of the Improvement, which would mean more money for enterprising people, and result in the eradication of famine and unemployment. Money for investment in the many projects he had looked at was there for the taking. Wasn’t the Marquess the richest man in the union? The one problem was getting the message across to the dullards inhabiting the glens. The Duchess had impeccable Scottish credentials, which would make the pill easier to swallow. People who knew her spoke of her charm and magnetism, her extraordinary intelligence, but the best thing about it all was that the English Marquess was besotted with his Scottish spouse.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 adriankirby

Photo Credit:

CC-0 adriankirby

As expected, they arrived early and waited about half an hour before entering the precincts of the Castle. He looked out of the carriage, admired the structure and the recent renovation which was tastefully carried out. Half an hour was not enough to take it all in, but no doubt the opportunity will arise soon for other visits, perhaps with dear Sarah. Since the Marquess had moved north to Sutherland, he had invested heavily in the modernisation of the seat of his beloved wife’s ancestral home. The castle had been built by the first Earl of Sutherland in the mid thirteenth century as nothing more than a fort, where he and his descendants had lived more or less peacefully until the Jacobite uprising which had damaged it considerably. The impoverished residents had not been able to afford repairs and modernisation, but it was the avowed aim of the new lord and master to turn his abode into the most lavish castle in the Highlands, to transform it from the fort that it was into a castle of fantasy that would match Versailles itself in splendour. However, as the noble pair wanted minimal disruption to their daily life, progress was slow. It was very much a long term project, and the Marquess said to all his friends and well wishers, ‘I guarantee that every time you come visit, I will have to show you at least one major innovation.’

Sinclair was politely ushered into the petit salon — small for Dunrobin — and served a glass of port by a flunkey and left alone to savour it. He was somewhat taken aback by this minor slight. Shortly afterwards, two other men joined him. They were introduced to him as William Young, a pleasant looking man of about his own age, and a younger man, Patrick Sellar, who had the strange eyes of a religious zealot. They too were served a glass of port and told that their Highnesses were going to join them shortly. They sipped their port quietly, hardly glancing at each other. A few minutes later the sound of raucous laughter was heard outside and when the door was opened, a garrulous and slightly dishevelled Duke walked in, a shock of platinum hair protruding out of his badly fixed wig. Sir John who was a stickler in matters of decorum and etiquette was somewhat surprised that his highness had taken such little care with his appearance. His face was red and shiny, and it was obvious that though not drunk, he had overindulged at lunch. He was looking very jovial and harrumphed his way in, extending both hands towards his guests, almost colliding with a large Chinese vase but stopping in time, wagging a finger playfully at the inanimate object, and reprimanding it for standing in his way. Sir John smiled, the two men laughed loudly and Stafford nodded approvingly.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND John Koetsler

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND John Koetsler

‘The Chinese may have slitty eyes,’ he said gruffly, ‘but that does not stop them producing masterpieces like that vase here, eh what? Or is it an urn?’ The three men nodded their agreement wholeheartedly. He greeted each guest by extending a limp hand for them to shake, but understandably for a man who had to keep so many balls in the air, he called him Sir James instead of Sir John. He believed that it was impolitic to point out this insignificant slip, but even after they had known each other quite well, the good Duke would always have difficulty remembering whether he was Sir Peter, Sir James or Sir John. He even allowed the suspicion that his lordship did this on purpose, as a sort of private joke, to contaminate, albeit ever so slightly, the good opinion that he had formed of the man from across the border.

He took a seat opposite his guests, snapped his fingers and a footman walked towards him gravely, bowed his head slightly and nodded as he acknowledged an order and left. He came back with a decanter on a silver tray and poured some port in a Murano crystal glass, and was about to offer it to his highness when the latter shook his head and with a sign indicated that he wanted more of the stuff in. The footman complied and Stafford happily grabbed the glass and immediately took a large sip from it, rather noisily, Sinclair thought. The two other men, Young and Sellar seemed unable to take their eyes off their host, and their admiration for him seemed boundless. They were no doubt taking it all in, already anticipating the admiration in the eyes of a putative audience to whom everything would be narrated in the near future. Sinclair was not one to pass judgment on his betters, but would have been happier if gravitas was more evident in the proceedings than frivolity, but he had no doubt that the good Earl knew what he was doing. Sinclair did not owe his success in life by questioning the action of his betters.

Duchess Elizabeth did not put in an appearance in the salon, but when a footman came in to invite them into the dining room, she was there at the door, smiling broadly at her guests, extending a hand to be kissed, and bidding them welcome to Dunrobin in the sweetest and most gracious of tones, and in an accent which was as English as it is heard at Buckingham Palace. Sinclair was stunned by her poise and elegance — class will always tell. He noticed her unique beauty, the shapely bosom, the wasplike waist, the peerless hazel eyes, the high cheekbones, the pointed chin, the lips that went on forever at either ends, the long legs and the statuesque physique. I will make a note of what she is wearing later, so I can tell Sarah, he said to himself.

Feverish with expectation, the learned man was unable to enjoy the fare, excellent though it was. The salmon, the Duke explained, came from Loch Brora. No, he wagged a finger to forestall any wrong conclusion that his guests might have arrived at, I did not fish it myself, but waylaid a poacher with a basket of my fish! I had him stopped and I whipped him myself — not as much as you would have thought —

The good Duke stopped at this point, and William Young, as if on cue expressed surprise that the noble lord would carry out the punishment himself and not hand the villain over to his gamekeeper, whereupon the good Duke laughed so much that he spluttered into his plate, to the amusement of his consort who shook her head merrily. For a whole minute the guests were left enjoying the manifestation of their host’s high amusement, and no words were exchanged. The Duke almost had tears in his eyes, and raising a knife as a mute prayer to the table to bear with him, as what he was going to say would be absolutely stunning, he finally managed to blurt out, ‘Cripes! Get the gamekeeper to whip himself like some demented saint?’

‘It was the gamekeeper himself who was the poacher,’ explained the Duchess needlessly. When the Duke had calmed down, he shook his head and began another wave of hysterical laughter.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY mike.horrocks

Photo Credit:

CC-BY mike.horrocks

‘You won’t believe this, but the venison roast had a similar provenance, but sad to say, it was Auld Tam this time, and my better half here has a soft spot for that particular villain, for the simple reason that she had known the fellow since she was a… wee bairrrn, as she put it… why that should whitewash the man’s trespasses, I shall never know, but then I am a lover of women and do not claim to understand them, eh what! So we let him go… even after the rascal refused to promise that he would not recommence! ‘No, sirrr,’ he said, ‘I cannae see why I shall refrain from serving masel of the good things the good Lord put on this good earth for ma sake, just because a man puts a fence roond the forests and declare that they belong to hissel!’ By now he had calmed down and solemnly added, ‘You’ve got to admire the spirit of the Highlander, eh what!’

They adjourned to the salon, where to Sir John’s mild surprise, it seemed that it was the Duchess and not the Duke who was going to preside. Her spouse was surprisingly quiet, and kept nodding off.

Sir John was asked to expound his views on the Improvement, and did so in clear concise words which came easily to him as he had given the matter much thought over the years.

‘As my mentor Adam Smith used to say,’ he began, but the Marquess interrupted him with a great burst of hilarity.

‘Did I hear you say Smith, my dear fellow? How can a man called Smith have anything sensible to say about anything, what piffle!’ The Duchess gave him a withering look which forced its way through a superficial smile, and he coughed, closed his eyes and began snoring instantly.

The Highlands which he knew intimately, Sinclair said, was singularly underexploited. It was wrong to believe that because the soil was not among the most fertile, that it could barely support crops like oat and turnips, that it had to be left to go to blazes. It was able to provide for a restricted number of Black cattle, he explained, but Highlanders are too set in their ways, too mentally lazy to think ahead and plan. The future was Cheviot sheep! He had worked out the arithmetic. The statistics, he called it —

‘Statistics?’ queried the Duchess, ‘what’s that, Sir John?’.

‘Aye, a new word I coined myself,’ he said proudly, ‘to describe how numbers can be used to give us an idea, using the notion of probability, of what outcome to expect in studies in various fields. Some clever mathematicians have made interesting discoveries in that area and we can gain a lot by making use of their findings. And I can demonstrate that a change from Black cattle to Cheviot sheep, what with the demand for wool in Lancashire, profits… eh… productivity, would be increased fourfold at a stroke.’

‘No one can accuse me of being hardhearted,’ said the Duchess with some vehemence, ‘when they were starving, I was there with my handouts. How did they pay me back? By refusing to join my Sutherland Fencibles. Either they were cowards refusing to fight for King and country, or they were ungrateful dogs who preferred other regiments to the one my dear father, their biggest benefactor had created.’

‘Aye, an idle and useless lot, ma’am.’ agreed Patrick Sellar, who had said next to nothing all evening.

‘Like everybody else, the Highlander is deeply attached to his land and his ways,’ said William Young in a slightly dissenting tone, ‘but he needs to be persuaded. We need time.’ Sinclair began suspecting that the man was only trying to exhibit a compassion that he did not really possess.

‘Time!’ roared Sir John losing his cool for the first time, ‘we do not have that commodity. We are richest nation in Europe and if we intend to stay that way, we cannot let lesser nations like France, Spain and Holland catch up with us, and they will unless we deal with the millstones round our necks by shedding them off, as soon as possible.’

‘We need to be sensitive,’ implored William Young, ‘we need to respect the people’s traditions.’ Sinclair was now convinced that Young was only mouthing these sentiments in order to convince himself and the audience that he was a thinking man and not a heartless exploiter. Sir John was not going to moderate his views.

‘God made eggs,’ he began on his familiar theme, and found it hard to hide his annoyance when Patrick Sellar interrupted him.

‘In my experience of Highlanders, they only respect force. If they know you are going to be easy on them and tackle them in a spirit of conciliation, you become putty in their hands.’

‘My first consideration in everything I undertake,’ began the Duchess thoughtfully, ‘is the well being of my Sutherlanders. They know they can depend on me, and as you’re all aware, when their crops fail and penury casts its chill upon them, it’s I and no one else who make sure they get a full belly… I wouldn’t let a single man on my land starve, even if they have disappointed me many a time. I am not vindictive, not even against those who have opted to join other regiments.’ Yes, indeed an admirable woman, Sir John thought.

‘What I was going to say,’ she pursued, ‘is that if people have to be relocated, then so be it. But I will make sure that any hardship inflicted upon them will be minimal. But sorry Sir John, go ahead.’

Sir John took a deep breath and explained about alternative sources of revenues for the undisciplined tenants. New fishing colonies that could be established on the west coast, kelp production, boat building, lime and chalk production. The vacated area would then be entirely dedicated to sheep, and everybody would be richer and, dared he say, live happily ever after.

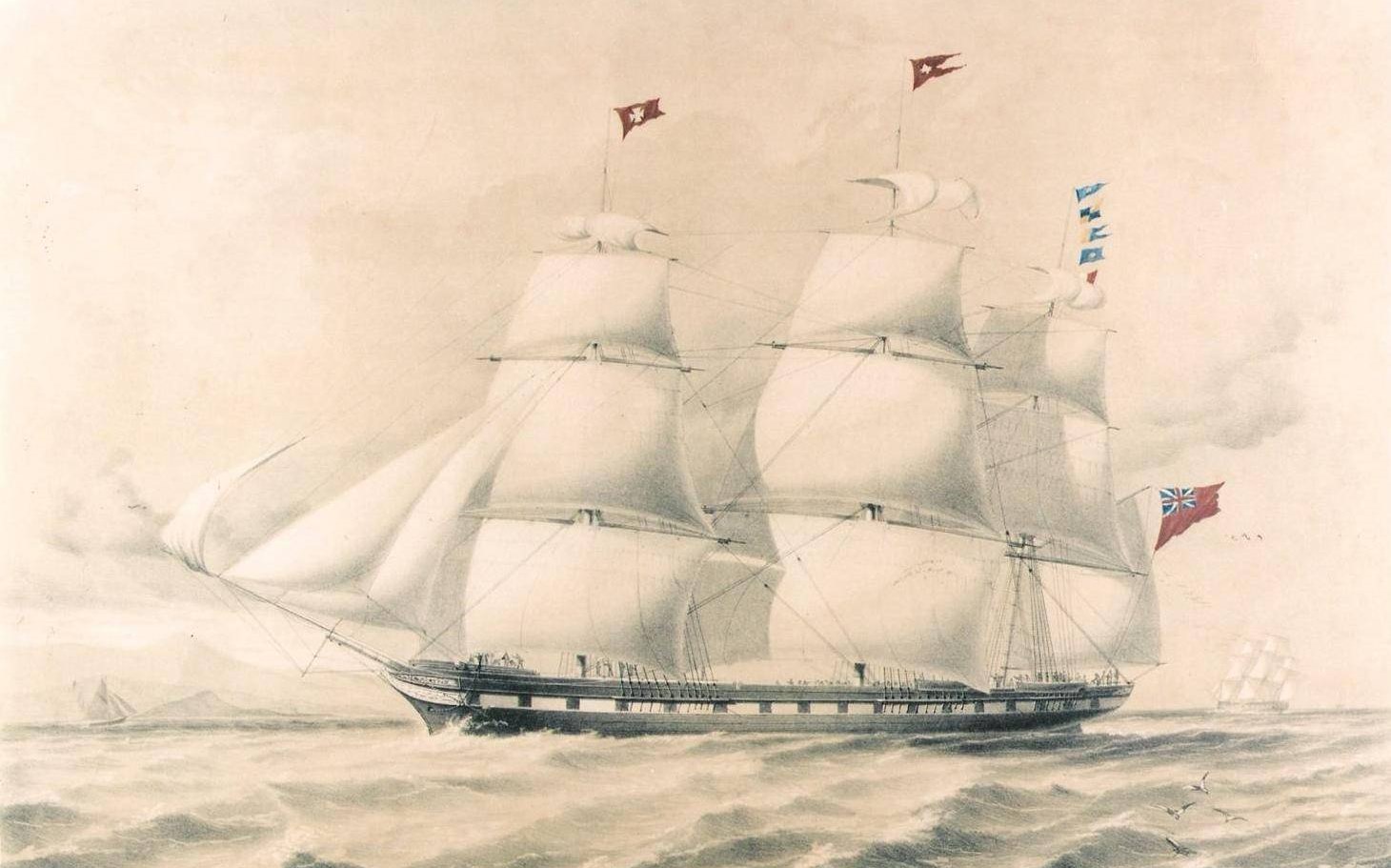

‘And if anybody does not wish to accept relocation and new openings, then they can emigrate to Canada or the Carolinas,’ said Sellar.

‘Or transported down under!’ guffawed the irrepressible Stafford, suddenly waking up.

‘Mark my word, ma’am’ said Young gravely, ‘Highlanders will not just pack up their things and go away because it suits us that they do.’ Perhaps he might be sincere after all, mused Sir John, sincere but misguided, but the Highlanders will have to do as they are told.

‘Piffle and balderdash my dear Young, if you allow me to say so — I’ve said it anyway, ha! ha! Piffle, balderdash and poppycock! The Highlander, from what I have seen of him, is workshy, mentally dead and lacks backbone. He will jolly well do as we tell him. Have you seen their children? If it was rather more than their mouths which were black from eating earth, they couldn’t be distinguished from the piccaninnies of our colonies.’ I would not have put it like that myself, thought the scientist, but I can’t disagree with the sentiments.

‘I think, your Lordship underestimates the enemy,’ said Young. Ha! I was right after all, he calls them the enemy.

‘What do you think, Sir John?’ asked the Duchess. Sinclair, ever the rational man, said that he had insufficient data to make a valid pronouncement, but he was sure that there would be problems, but equally sure that problems of that nature were not insurmountable.

After some deliberation, Sinclair said he had to inform his highnesses that there would be not inconsiderable costs to the exercise, whereupon the Duchess solemnly said that for the welfare of his Sutherland Highlanders, she would not hesitate to disburse however much was needed, which triggered another blast of hilarity from the Duke.

‘Dear heart,’ he said goodnaturedly, ‘the first reason why you would not hesitate to disburse, is that it’s my money,’ but to the relief of everybody, he quickly added, ‘but what is mine is yours of course.’ He took a deep breath and continued, ‘And the second and probably more important reason is that you know that any amount spent is an investment which will indubitably double in a year.’ Everybody laughed heartily, nodding their agreement with the assessment. I wish he’d go back to sleep, thought Sir John.

Sellar explained that he was speaking in the name of William Young as well, he hoped. If the Duchess meant to implement her plans, then they, her representatives, must be given free rein to act as they thought fit.

‘What can you mean, Mr Sellar?’ asked Elizabeth Gordon.

‘There is only one thing to do once the tenant has been legally evicted, and I take no pleasure in saying this your Highness, their habitation needs to be burnt down, or they would come back and no one will be able to stop them reoccupying their former abode.’ For the first time the Duke assumed a serious pose, bit his lips and frowned. Then he shook his head glumly.

‘I can see that this course, heartless as it might seem on the surface, cannot be avoided. But I must strongly emphasise that I want no more than minimal violence, and under no circumstances will I tolerate loss of life.’

‘Dear heart,’ the Duchess said, ‘haven’t Mr Young and Mr Sellar already impressed us by their compassion, their common sense, and their attachment to our Christian values? They are not men who are going to cause unnecessary harm to those churls.’

‘Your ladyship can trust us on that score,’ Young assured her, ‘I am a man of peace myself, as the tenants well know from the long association I have had with many of them. We will handle this matter with utmost judiciousness and delicacy,’ adding, after a pause, ‘firmness and… eh… delicacy.’

‘There is one important thing I must make clear to you,’ said the Duchess earnestly, ‘when the churls are resettled in fishing villages, they are not to be given leases.’

Everybody looked at her in surprise. She smiled with self-satisfaction and explained that this would make it easier to evict them legally if they are troublesome. Surprise immediately turned to admiration. What intelligence, what manly determination! They shook their heads and smiled. The Duke positively glowed with pride at his wife, and beamed at her lovingly. The footmen then served dessert.

‘Gentlemen, you will love this special creation by François, our new directeur de cuisine. It is something our illustrious Gallic neighbours called Crêpe, and he has himself invented this new sauce which he makes with a heavenly liqueur created by monks, called Green Chartreuse.’ Everybody partook of this excellent offering and pronounced it… heavenly.

The session ended on an upbeat note, and Sir John went home happy in the thought that he had laid the foundation stone to greater things to come, a new departure for a deprived area. With the admirable work Thomas Telford was doing, building a canal through the Great Glen which would facilitate transport of goods, the people who had advanced the views that Lanarkshire would become another Lancashire before the middle of the century, were soon going to be proved right. He was quite sanguine about that.

Young and Sellar were asked to come back to Dunrobin within a week, when the Duchess would consult with them about the nuts and bolts of operations. But not tomorrow, she said, explaining that she had promised her godson who had come over to spend part of his vacation at Dunrobin, with two Etonian friends that she was going to devote the whole day to them.

Unbeknownst to all those clever people, Albert the footman had picked a fair bit of what had gone on, and what he had missed out was soon filled in by patchy intelligence from attendants, cooks, other footmen and lackeys. Albert was one of the few friends of Angus Smith. Hugh had been extremely discreet and careful, for he had known from the very outset that a slip on his part could mean recapture, resulting in hanging. He constantly repeated this to his wife and Mam, and made them swear on the good book that under no circumstance would they reveal the truth about what had happened to them, even to the many good friends that they had made since moving to Strathnaver, and certainly not to the children.

Albert had always thought that there was an aura of mystery about this Angus Smith, and it was perhaps this that had made him want to become his friend. He knew that once a fortnight he came to Golspie on business, and often joined him at the Stag Heid for one jar of the local brew. Angus would drink his ale slowly, and leave the moment he had emptied it, he never had a second one, not even if it was offered to him. That afternoon the footman made his way to the Heid, and as luck would have it, his good friend was there. Hugh got Albert a jar of the rather excellent barley ale that Daniel the landlord offered, and the two men sat down and talked.

‘The Duke and Duchess are making trouble for oor Highlanders my friend,’ Albert said gravely, ‘and their plan is a mighty wicked one, I daresay.’

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Gail

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Gail

When Kitty got home, it was her eyes which betrayed her. First they tried to look away and avoid contact with other eyes, and when that was unavoidable, they stared at you and looked clean through you. Hugh noticed it immediately, you had to ask her everything twice, and she blinked when answering, got her words mixed up and blushed. Hugh mentioned this to Martha who nodded and shrugged. It was to Grand Mam that she confided.

During the school holidays, Kitty often took the cattle out to graze. She did this because she wanted to do her share of work, but she very much enjoyed the outdoor life. She had been full of silent foreboding when the family moved to the area after Fort Williams, but the moment she saw her glen, her apprehension instantly evaporated in its enchantment. She had been struck by the silence which was accentuated by the faint murmur of a stream. She loved to sit under her giant oak, feeling like Mr Cowper’s Alexander Selkirk, mistress of all she surveyed. The munro at Loch Lunn seemed to have two distinct personalities, baleful and menacing when the clouds hovered above, and the exact opposite under a spring sun, almost skittish, specially when the ground started vibrating with heather. From her vantage point, she would contemplate the gentle slopes which turned gold in summer and exult in its splendour. As a child she used to think that the small nameless loch in the distance, gleaming in the sun, was a silver mine. What she liked above everything was a shock of green which unexpectedly burst out from one of the ridges, a cluster of pine trees. She often wondered, why just there? In those carefree days, she and John and other young ragamuffins from the hamlet often used to run around this oasis, up and down the undulating ridges, throwing sticks at each other, screaming like banshees, their hands spread out like birds ready for take-off.

She was almost certain on any day to catch a glimpse of the wildlife. Her heart would beat with excitement when she saw a red deer in the distance, framed by the greenness of the glen, often followed in a trice, by two or three more. It was a sight that made her wish she was a painter able to encapsulate the heart-throbbing beauty of that instant on canvas. She would hold her breath as they were such timid creatures and would disappear into the growth in one leap when disturbed. Sometimes a pine marten would dart from one end of the clearing to the next, as if pursued by a hunter after its fur. Already this year she had seen two golden eagles hover majestically in the peerless sky above. She loved to sit in the shade of the giant oak, knitting or reading a parchment scroll which Miss Black had lovingly copied in her simple but firm handwriting for her pupils, and circulated among them.

This morning she had heard a strange commotion and turning her head round, she had seen a most unfamiliar and glorious sight. She had never seen a capercaillie before, and there in front of her were two of them! They were striking looking, with red circles around their eyes, their beaks aimed at each other; it was obvious that they had been fighting, and had gradually pushed each other outside the forest into the clearing; their tails were spread out like fans and their wings trailing the ground, with the feathers round their neck puffed out. They made strange growling noises and they moved their menacing beaks up and down in unison but without making any serious attempt at having a stab at the other. Kitty looked at them in wonderment, holding her breath, wishing that they would not harm each other, and on an impulse decided that the best thing was to shoo them away as a means of protecting them against each other. She stood up and hollered at them, and they turned away from each other and clumsily flew away, making a whistling noise with their wings as they did so. She was delighted, both with the sighting and with herself for what she thought of as her good action for the day.

She watched the clouds disappear behind the mountain and leant against her tree as against a lover. She loved the Robin Hood tales, and she had been looking forward to reading the tale of the Golden Prize. She loved reading aloud, and at home felt uncomfortable doing that in everybody’s hearing, with John sneering, albeit good-naturedly. She would only read aloud to Grand Mam, who had after all given her, her love of stories. She had a quick glance at the cows. They were happily chewing their cud, and were not too near the drop, which they instinctively knew how to avoid anyway. She took a deep breath and declaimed in a monotonous manner:

I have heard talk of bold Robin Hood,

Derry derry down

And of brave Little John,

Of Fryer Tuck, and Will Scarlet,

Loxley, and Maid Marion.

Hey down derry derry down

She stopped and shook her head. No, her delivery was so humdrum, she was going to do it again. She smiled, made sure nobody was within sight or earshot, and started again, this time putting emphasis on certain words.

I have heard talk of bold Robin Hood,

Derry derry down

And of brave Little John,

Of Fryer Tuck, and Will Scar-let,

Loxley, and Maid Marion.

Hey down derry derry down

She knew that she sounded ludicrous, but it did not matter, she was having fun. She did it again, and began to sing the Hey down derry derry down bit. I am losing my mind, she said to herself and giggled. She read the next bit.

But such a tale as this before

I think there was never none;

For Robin Hood disguised himself,

And to the wood is gone.

She again played with this verse, reading it in different styles. She noticed that the cows had strayed a bit too near the drop, and carefully wrapping the scroll in her shawl, and putting a stone on it for protection against the wind, she stood up and ran towards them, and tapping her crook on the ground instructed them to move away towards safer grounds, after which she went back to her cosy little seat under the oak and picked up her scroll. When she came to the bit,

Two lusty priests, clad all in black,

Come riding gallantly…

She was so engrossed by images of Sherwood Forest and the valiant men who were willing to shed their lives in the defence of the poor oppressed people, she could even hear the sound of hoofs approaching.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Roger Buntin

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Roger Buntin

‘Benedicete,’ then said Robin Hood,

‘Some pitty on me take;

Cross you my hand with a silver groat,

For Our dear Ladies sake.

She loved the word Benedicete, and she repeated it a few times, giggling as she did so. What can it mean? she wondered. To her amazement, she heard “Benedicete, fair wench!” and looking up, she saw three handsome youths in their finery, on horseback, looking at her in amusement. They were striking looking, had almost identical chestnut mounts, but she knew nothing of horses, and supposed they were Arabian. She blushed and thought of running away.

‘I am sorry, your lordships,’ she stammered, not feeling confident speaking English ‘I, eh… I… didn’t know… I mean I wasn’t doing any harm…’ and she found herself suddenly having to battle against her tears.

The three young gentlemen got down their mounts and in a clearly unthreatening manner took two steps in her direction. She did not dare lift her eyes to look at the young men, but felt that there was no danger.

‘What is it you are reading, wench…’ one of the trio asked and looking up she saw one of the handsomest youth she had ever cast eyes upon. She was too confused to answer, and was grateful when a second youth spoke.

‘Don’t be afraid, wench, we are completely harmless. I am Robert Helmsdale-Robertson, the Duchess of Sutherland is my godmother. This uncouth pair here call me Rob Rob. This chappie here is Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley. One day he will become the Poet Laureate of England, or so he tells everybody, and this runt here is George Henry Blake, who hopes to turn the Union into a socialist Utopia one day. We are all staying at Dunrobin at the moment.’

And to Kitty’s amazement, George Henry bowed to her solemnly saying ‘Ma’am!’ whereupon the other two nodded and smiled. She was confused and blushing all over, but relished this first time that anybody had called her ‘Ma’am’.

‘What is it you are reading… miss,’ asked George Henry, and Kitty stammered her reply.

‘You have a good reading voice,’ said Shelley, and he extended his hand towards her in a wordless request that she let him have a look. With trembling fingers she picked the scroll and handed it over to the aspiring poet. He looked at it, obviously reading it, nodding to himself.

‘Listen to this Blake, Rob Rob…’

The priests did pray with mournful chear,

Sometimes their hands did wring,

Sometimes they wept and cried aloud,

Whilst Robin did merrily sing.

‘The hypocrites! Your first priority, come the revolution Blake, is to sort out those parasites.’

‘Do you enjoy reading then, young… lady?’ asked Rob Rob.

‘What a silly question, Rob Rob! Would she be reading with such gusto if she did not?’ That was the handsome one called Shelley.

Kitty wanted to ask what ‘gusto’ meant, but she had been dumbstruck, and felt that it would be wrong to ask questions of young lords.

‘I do, sir,’ she heard herself say, looking at Rob Rob for the first time. He was slim and had a noticeable tan, but his eyes were quite uncommon, very attractive, they seemed almost almond shaped.

‘Miss Black…’, she started but stalled. She wanted to say something about her much loved teacher, but was not quite sure what or how, so she stopped. Rob Rob was not only good looking, but everything about him exuded gentleness. Kitty did not tell Grand Mam that she had been unable (or willing) to shake off images of that young man from her mind’s eye ever since she had cast eyes upon him. A worm can look at a star!

‘What’s your name and where do you live?’ asked Rob Rob.

‘Catriona Smith. We bide in Aiktree Farm.’

Rob Rob said he knew where that was.

‘Will you do us the honour of reading some more of the ballad before we go, Miss Smith?’ asked Blake, and Kitty did not immediately realise that the Miss Smith referred to was herself, and when she did, she blushed and knew that there was no way she was going to be able to oblige although she would have liked to. She shook her head violently and looked away. The young men who had referred to her as wench to start with, subsequently treated her like a real lady, and she was deeply touched by this. They bowed courteously and took their leave, and she could not help noticing that Rob Rob turned round several times to have yet another look at her.

‘She is in love,’ Mam said to Hugh. ‘It’s a nice feeling, it will do wonders for her self-confidence, but trust me, nothing bad is going to happen, do not spoil it for her, just let her savour the moment. Dreaming never harmed anyone. She is not likely to see the young man ever again.’

But she was wrong.

Next day Rob Rob turned up alone at Aiktree, with a bundle. Grand Mam who was outside became greatly agitated and confused on seeing the young toff. She blushed and curtsied, and to her amazement, the young man took off his fine hat and bowed to her in return.

‘May I bid you a good morning, Ma’am?’ said the young man in faltering Gaelic. Mam had never in her born life been called Ma’am either, and blushed some more. She had heard stories of young girls losing more than their heads to these young aristocrats, and for the first time she understood how difficult it was for the likes of them to resist these well-born swains. When all your life, you experience humiliation from all corners except from your very own, and someone from another world started treating you like you mattered somehow, how can you not lose your head? But of course Catriona had a sound head on her shoulders, and was not likely to lose it.

‘I am Rob Rob,’ said the young man, ‘my godmother is…’ he was unable to finish the sentence, but Mam nodded eagerly, making it obvious, without meaning to, that Kitty had told her the whole story. She noticed how the young man was struggling with Gaelic, and was on the point of telling him that she understood English quite well, but changed her mind at the last moment. Let the arrogant masters suffer for once.

‘I have got s-s-some books and p-parchments for…’ he stammered, leaving his sentence unfinished. She suddenly relented and explained in English that Kitty was out, as was the whole family apart from her. He handed the bundle over to her, bowed again, walked to his horse and skilfully manoeuvred himself into the saddle and ambled away. Mam, stood there, holding the bundle, as if paralysed, unable to move or even to think, for some time.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 wittkielgruppe

Photo Credit:

CC-0 wittkielgruppe

Rob Rob guessed that Kitty would be where he had found her the day before, and he was right. There was she, seated under her oak tree, knitting. When she heard the sound of gallop, she closed her eyes and prayed that it would be Rob Rob, and found it hard to hide her joy when her prayer was answered. Thank you God, she whispered to herself. He, wanting to impress her, spurred the chestnut on and made him stop within touching distance of her, and she was so sure of the skill of the young man that not once did she flinch. They both laughed. He patted the horse on the head, and the latter responded by neighing in his direction with obvious warmth.

‘I call him Silliboy,’ he said, ‘but only because I love him.’ She said nothing.

‘Is it for me you are knitting this lovely… eh… scarf?’ he asked. She blushed.

‘They are mittens for the neighbours’ new baby,’ she said, raising her head to catch a good look at the man she had now fallen head over heels in love with. The fact that he had come looking for her was proof enough that he felt the same way about her. She nearly said that if she had the wool, she would love nothing better than to knit something for him.

‘I’ll ask godmother for some wool,’ he said earnestly, ‘then you can knit me… a scarf, can you?’ She nodded, and he added, ‘I’ll pay you for your trouble of course.’

Kitty was a quick thinker, and instead of taking offence, she immediately thought that if she got paid for it, be it ever so little, she would be able explain to Martha and John that she was doing her bit for the family, and deviate any criticism that might come her way, to the effect that she was behaving like a romantic fool. The distant strains of a flute played by some cowherd surreptitiously strolled in on the gentle breeze, and they became aware of it at the same time.

‘It’ll be a pleasure, sir,’ she said. He wanted to ask her not to call him sir, but Rob Rob, but he found it difficult. All his life, he had been aware of his position, there were Us and Them, and he did not know how to talk to one of Them as if he or she were one of Us. And he supposed that Kitty would experience the same dilemma. But he said it anyway.

‘Kitty… can I call you Kitty?’ he began, but did not wait for an answer, ‘Kitty, my friend Blake has done something marvellous to me, he has shown me that all men are equal… eh… all human beings… not just men, you see, I mean all women are equal too… eh… to women… and… eh… not just women, but… Oh Kitty, if only you knew, I am in awe of you, and I am losing my power of speech…’ She blushed and thought that she should not let him know how smitten she was.

‘What I was trying to say, Kitty, is that you should call me Rob Rob… and think of me as a… eh… friend.’

‘Oh no, Rob Rob, it wouldn’t be right to call you sir,’ she blurted out, meaning to say the opposite, and he burst out laughing. She did not immediately identify the cause of his hilarity, but the sentence echoed in her mind, Oh no, Rob Rob, it wouldn’t be right to call you sir. And all she could think of doing was to cover her eyes, as if this negated the slip of the tongue. He bent forward and gently took her hand and pulled it away from her eyes. The contact with him made her shiver with a feeling she had never experienced before. She wished he would stroke her bare arms with his gentle hands. He too became aware of a strange sensation as they made their first ever physical contact. He wanted to keep her arm in his, and take her in his arms and hold her, but the revulsion with which he held those peers of his at Eton who boasted about how they had coerced servant girls and milkmaids to offer them sexual services made him pull away. She knew clearly why he did, and was grateful. He was indeed a sensitive soul, not someone who would take advantage of a poor crofter’s daughter.

‘I left some books… things to read anyway… with your Grandma. I asked Godmother for them. She is so kindhearted.’ Just as she was wondering about how she would return them to Dunrobin, he said, ‘The Duchess says you can keep them.’

‘She is very kind… you are very kind too… thank you.’ And she curtsied clumsily, and he laughed.

‘You shouldn’t curtsey to me, Kitty, you must not think of me as… you know… I am your friend… I mean I want to be your friend if you will let me.’ She did not answer but smiled. Yes, he loves me too, she said to herself, that’s the important thing even if I know that nothing can come out of such a love. Blake is right, he was thinking, we should break down those artificial barriers between people, we are all the same, our blood is of the same colour, only some people have not had their fair share of the good things of life because we the rich have taken too much for ourselves. The balance must be redressed, and I will make a start. For the first time the idea that he might marry Kitty some day, set from a wobbly fantasy into a concrete certainty. Yes, he believed in love at first sight. The girl had intelligence, beauty, and everything about her reflected gentleness and wisdom. Yes, strange to say, wisdom was the first thing that he surmised about her. It was in her eyes, and it was strange, he thought, that one so young could exhibit such clear signs of it, without doubting for a moment that someone of his tender age could have the wisdom to recognise this. This was Serendipity! He had found true love, without looking for it. A cowherd was his soul mate. He was sure that he wanted no one else to share his life. He did not know how he was going to manage that, there were many obstacles, but he felt so strong that he was sure that he would dismantle them all one by one. He must confide in Shelley and Blake.

They just stood looking at each other, silently, both yearning to be in the other’s arms, but keeping sunlight between them. In the distance the cows were contentedly chewing the abundant grass of the slope.

‘I am going grouse shooting tomorrow,’ he said regretfully, ‘with Shelley and Blake, Godmother has planned it for us and says she might join us.’ He paused, and added, ‘If you knew how much I care for her, she has been like a mother to me.’ He looked at her to see whether she was interested, and decided that she was, so he continued. ‘You know, my father is in Penang… I haven’t been in years, but he is arranging for me to go on a visit next year…’

‘Penang?’ Kitty asked, and he explained that it was in the Far East, and that his father was the head of the British East India Company which was trying to develop that very rich part of the world for Britain.

‘Blake calls it exploitation,’ he laughed, ‘but I don’t know, I mean the natives do not have the know-how.’ Kitty was lost, she had little idea of the world. At sixteen she was still struggling to learn to read and write. Miss Black taught them everything she knew, but besides the handful of books she had, it was mainly the bible, composition, and some arithmetic. She read everything she could lay hands on but there was not any great choice, so she read everything a few times over, until she knew almost everything she read by heart.

‘What is exploitation?’ she asked timidly.

‘Exploitation?’ He repeated and laughed. ‘How shall I put it? It is when someone who has the power, makes other people do the donkey work for him and reaps the biggest share of the profits.’ He paused for a bit and nodded to himself before continuing. ‘Let me give you an example: my father goes to the colonies, he claims the native does not know how to get the best from the natural resources of his land, so he distributes seeds and seedlings of the rubber plant which he brought over from Kew Gardens and gives them instructions. Then he sits in an office, let them do all the hard work, shows them how to produce rubber, which… eh… the native doesn’t know what to do with, so he takes it from him and make huge profits out of it, but the native only gets a bowl of rice for his pains.’

Kitty saw clearly what Rob Rob meant, and smiled before she spoke.

‘Isn’t that what is done here as well?’ She asked, the young man frowned.

‘Here?’

‘Aye! My father, Mam, Grand Mam, my brother John and I we all work pretty hard raising our cattle, growing our oats and barley, our potatoes and turnips, making butter, knitting late into the night until the light fails, but it is the landlord who becomes rich. That’s what I mean, sir. Would you call that exploitation, sir?’

It was Rob Rob’s turn to blush now, taken aback by the words of the young peasant woman. He had always heard the Duchess speak of the poverty of the Highlanders, their laziness and deviousness, their drunkenness and lack of discipline, how they would be starving without the charity of the rich. Over the years this had naturally become his view too, although it was a view which was beginning to erode as Blake began expounding the theories of Hume and Locke.

‘Yes, I-I-I s-s-suppose you are right…’ he stammered unconvincingly. He was now assailed by emotions and doubts which set his mind in a turmoil that he had never experienced before. Surely Godmother was not talking about Kitty and her folks, and the young woman was talking generally about the landlord class, not about her dear Mother Substitute, as near a saint as can be imagined. Maybe it was not such a good idea to make friends with someone who was of such different class. Damn Blake for suggesting otherwise!

The young man who a few minutes ago was full of carefully rehearsed and lyrical sentences he was planning to say to the young lassie, now found himself tongue-tied. I must be off now, he said, walked towards his mount, and this time got on it in a less spectacular manner, nodded gravely to Kitty, then forced an apologetic smile on his lips, saying that Shelley and Blake were waiting for him, and he galloped away.

Kitty understood that it was what she had said which had produced this sudden drop in temperature, but felt that he had taken her words amiss. She did not mean to say anything condemnatory. She had always accepted the exploitation of her class as a fact of life, one complained about the weather, but knew one could do nothing to change it, so one laughed and joked about it. She had heard about the Duchess but felt no animosity towards her, although she knew that Da and John did. She hoped that she had not frightened Rob Rob away for good.

After a copious dinner, the Duke and the Duchess invited their young guests to the petit salon, and were in jolly spirits, specially as they had seen clearly — or so they thought — how they would finally turn their Sutherland property which had so far been a sponge for Stafford’s not so hard earned legacy, into a profitable concern. The man had not only inherited his father’s considerable wealth, but shortly after the latter’s death, he found himself heir to the recently deceased Duke of Bridgewater who was equally rich, making him by far the richest man in the Union, richer, they said, than even His Majesty. In Europe, only the Romanovs in Muscovy were wealthier.

It was the first time that the Duchess was going to entertain his young guests in a fitting manner, and the Duke knew how much she valued young Helmsdale-Robertson, even wondering sometimes if she did not treasure the young man above their own.

Rob Rob had obviously written to her at great length about the young poet and his unconventional ideas. Normally she would have discouraged the friendship between the two, but her godson had mentioned that he was a descendant of the Earl of Arundel, and Elizabeth could not imagine that with such a lineage he could mean all those scandalous things the young poet claimed he would do to the ruling class. She found herself fascinated by him though, thought that his radical ideas were daring and exciting in theory, but hoped that as he matured they would make way for more sensible ones. And he was of course indubitably the handsomest young man she had ever cast eyes upon! If only I were ten years younger, she had sighed. Perhaps she really meant twenty. Strangely the Duke seemed equally fascinated by the young socialist Blake and thought he would have some fun baiting the boy.

‘Tell me, Mr Blake, your Mr Hume, was he or was he not a Christian?’ Blake loudly maintained that Mr Hume was definitely an atheist, whereupon the Duke shook his head and smiled.

‘You’re wrong there, young man, your Mr Hume definitely embraced Christianity, trust me.’

‘Not Mr Hume.’

‘Aye,’ said the Duke who found himself borrowing Scottish words and idioms more and more often, possibly to tease his wife. ‘And I’ll tell you the how and the when of it if you like.’ Young Blake said nothing.

Hume, he began, was having a house built in David Street, in Edinburgh, and whilst on his way to inspecting the works, he fell into a mire. As you know, since you are an admirer of the man, he was of great bulk and could not find his feet. Some fishwives happened to be passing by and he shouted for help. They came running and were on the point of rescuing him when one of them said, But that’s the Mr Hume who denies the existence of our Lord, let him perish! On hearing this, the women decided to leave him to his fate and go about their business, but one of them said that they would not be doing their Christian duty if they let the man sink in the mire and drown, for all his ungodly views, whereupon the other women came up with this excellent idea. Right, Mr Hume, we will save you if you renounce your cursed beliefs and recite the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed, which, the Marquess assured his young audience, he did with rare enthusiasm.

‘I am sure this is apocryphal,’ said Blake dismissively. The Duke did not know what that meant and shook his head dismissively.

‘You’re wrong, Blake,’ said Shelley, ‘Hume himself wrote about the incident to the Mure of Caldwell, and said that he had never met more acute theologians than those fishwives.’ The Duke seemed very impressed and nodded in admiration.

They were served French liqueur and strawberries. Blake had never seen them before and asked what they were. The Duke welcomed the question, as it was not often that he was able to air his erudition.

‘The Strawberry, as you can see is the prettiest of all fruits!’

‘Yes,’ sneered Shelley, ‘but your God spent so much time making it pretty that he forgot to give it any taste or flavour.’

‘Ach! That’s because God did not have Lachie as his chief gardener,’ roared the Duke, ‘I trust Mr Shelley that after you have tasted the fruits he grows in my glasshouse, you will change your mind.’ Shelley bowed slightly, half admitting the possibility.

‘It came to us from the Americas. Madame Whatshername, a famous companion of Robspear used to bathe in crushed strawberries to keep her skin soft. Mind you it did not help keep her head on her shoulders when her time came, ha! ha! ha!’ He paused and a twinkle in his eyes signalled the next bon mot.

‘Taking baths of any sort did not do any of them any good, eh what! Look at what happened to Marat.’ He expected an explosion of hilarity, but only mild amusement resulted.

‘Didn’t Fontenelle who lived to be a hundred swear that he owed his longevity to eating huge quantities of strawberry all his life, dear Heart?’

‘You’re absolutely right, dear Heart, he did,’ the Duchess said this aggressively to hide the fact that she had never heard of Fontenelle.

Shelley admitted that Lachie had done wonders, that he conceded that those particular fruits were indeed more fragrant than he remembered.

‘Mr Shelley,’ said the Duchess, ‘aren’t you going to entertain us by reading one of your poems, my godson is full of praise for their excellence.’

Shelley did not want to, and shook his head, saying that having written a piece he tended to forget it as he had poor memory, and he did not carry any copies with him when he travelled. Blake interrupted him and said that he happened to have saved a copy of a poem Shelley had shown him and then committed to the waste paper basket. He had liked it so much that he enjoyed having a look at it now and then. Producing it like by magic, he gave it to the young poet. He looked at it and shook his head. No, he said, shaking his head, I am not reading this piece of trash. It is clumsy and inchoate, the rhythm is all shaky, I am ashamed of it. However after a lot of entreaty mainly from the Duchess, he relented, and read:

I met a traveller from a distant land

Who said: Two colossal legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand

Buried, a ruined village lies, whose frown

And wrinkl’d face and look of cold command

Show that well the artist those passions read

Which still survive, stamp’d on these lifeless thighs

The hand that mock’d them and the heart that fed

And on the pedestal those lines appear

I am Rameses the Great, King of Kings

Look on my works ye mighty and know fear

Nothing more remains but sand and decay

Of that gigantic wreck stark grim and bare

The lone and level sand stretch far away.

‘What’s wrong with that?’ asked the Duke, ‘I very much doubt that I could have done any better myself!’

‘It’s got some great rhymes, some excellent rhythm —’ protested Rob Rob.

‘For me,’ the adamant young poet said, ‘unless I am one hundred percent satisfied with a piece, it is worth nothing. I swear to you that this will never see the light of the day.’

‘It is a great piece as it stands,’ countered Rob Rob, ‘it tells us like nothing else that I have read, about the impermanence of material things, that one day even Dunrobin Castle will fall into ruins.’ He paused and to everybody’s surprise, he had tears in his eyes as he continued.

‘Shelley, you have helped me to understand that only love matters!’ Everybody looked at him like he had lost his reason.

‘So my little boy is in love,’ said the Duchess, walking towards him and taking his hands in hers and fondling them. Rob Rob blushed, rose and walked out.

‘Love is a strange potion,’ said the Duke making a funny face, at which his dear Heart gave him a disapproving look. Shelley took out a little notebook and scribbled a few lines in a notebook.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 jarmoluk

Photo Credit:

CC-0 jarmoluk

When Kitty arrived home, she found the bundle on the table which John had made from wood he had gleaned here and there. It was such a pretty polished piece that it looked out of place in their shapeless hovel. She rushed to open the parcel. There were Caxton publications of Horace Walpole’s Castle Of Otranto, Mallory’s Morte d’Arthur, The Three Princes Of Serendip, but what Kitty was most impressed by a massive tome, handwritten in Chinese ink, called Stories From One Thousand And One Nights, Translated from French by William Gray with the gracious permission of Antoine Galland, commissioned by and dedicated to His Highness Sir Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater. She knew that she was going to love this book most. She sat down on the floor and was about to start reading when Hugh entered. Everything about him reflected his gentle nature. When he walked, he did so carefully as if he wanted to avoid hurting the insects on the ground. He moved gracefully, and whatever stress he might be under, he kept his mood under control. He had a relaxed face, rarely scowled and never raised his voice.

Hugh stared at the books and scrolls sadly, and Mam explained their provenance.

‘So you take gifts from my enemies,’ said Hugh curtly, ‘from people who wanted me and our kind dead.’

‘Rob Rob is not our enemy, Da,’ his daughter said softly. But he said nothing and left to go sit outside, his head in his hands. As Martha was coming from the fields, she immediately saw her husband’s sorry condition and she took his pipe and tobacco to him, and he smiled at her and lit it with his flintlock. She sat by his side, as close as she could to him, but said nothing. Kitty watched them from inside the house, and was relieved when after a while she saw him begin to talk. Martha had the power to soothe all aches and pains by just listening to you. She wondered if she had loved Da as passionately as she loved Rob Rob. Da’s enemy! Rob Rob could never be anybody’s enemy. He had left in a huff earlier on, but she knew that he would come back. How she wished it would be tomorrow, although he had said he was going hunting with the Duchess. Forty-eight hours, over two thousand minutes! How would she manage that? She shuddered at the thought that Da could have ordered her to stop seeing the young man, and did not know how she would have responded to that.

Next day, she carefully wrapped the precious One Thousand And One Nights in an old shawl and took it with her when she took the cows to pasture. When they had settled down nicely in their routine, she took the book out and began reading. She began reading the story of Aladdin and The Forty Thieves, and had reached the point where the boy rubbed the lamp, and like magic, it was Rob Rob who appeared in front of her, holding the reins of the horse. She had not even heard the sound of the horse’s hoofs, had not noticed his approach or his dismounting. She was dazzled, half by the enchantment in the story, and half by the magic of real life. How can Rob Rob appear to me when he is out hunting? Just by reading about magic? He was saying something, but she only caught the gist: the Duchess was indisposed and had to postpone the hunt. Kitty had to scratch her head in order to make sure that the presence was real. He extended his arms to her, and she stood up like a Jack-in-the-box and flung herself at him. He wrapped her in his arms and held her tight, inhaling the odours of her smoky clothes mixed with her honest bodily sweat with relish, gently stroking her back and waist. Kitty who had never been kissed before closed her eyes and raised her face to him, bent forward and he kissed her, at first tentatively, then finding her response encouraging, he put more passion in it.

‘I love you Catriona Smith, and I swear that I shall always love you.’

She had never heard sweeter words in her life, and closed her eyes, saying nothing, relishing the moment. She knew that the last thing she would recall before dying would be this event, these words, and even thought that if she died there and then, she would die happy.

‘I love you too, Rob Rob,’ she whispered, ‘I’ll never love anybody else.’

They pulled apart at the same time as both felt uncontrollable desires rising in them and knew that it would be dangerous and wrong to pursue that path, although in the grip of passion each would have yielded to the other’s wish.

Again she would confide in Grand Mam.

‘Lassie,’ her grandmother said finally, ‘love is a wonderful thing, but nothing good comes out of a poor crofter’s girl falling in love with a son of the Castle. All they want is their wicked ways with you and when they have got it, they leave you. They do it as a sport in order to go and boast about it to their friends.’

‘No,’ shouted Kitty angrily, ‘Rob Rob isn’t like that, I’ve told you, you’re just being…’ she stopped herself saying nasty, and instead said, ‘overcautious…’

‘Overcautious, am I?’ said the old lady, taking it just as badly, not quite sure what she meant, but she stopped short of showing anger. ‘Just think about what I have told you and don’t do anything that you will regret for the rest of your life.’ Whatever I do with Rob Rob, Kitty thought, I will never regret it.

That same night, the Duchess wrote a letter to Helmsdale-Robertson in Penang. When the two of them were teenagers, they had imagined that they were in love, but she had always been ambitious, and aspired to marry a very rich man of her own class, a duke at least, someone with the means of restoring her patrimony. He was from a more modest background had not dared risk a refusal, so their affair had been lukewarm, but both had kept fond memories of their first kiss on a boating trip on Loch Brora, the balls and picnics they had shared. At eighteen he had been commissioned and had ended up Captain Francis Light’s second in command when he had landed in Penang. It was of course Light who had negotiated with the Sultan of Keddah and secured Penang for the British East India Company, and thus for the British Crown. He had been very impressed by young Helmsdale-Robertson and had arranged for his proté to become Head of the Commercial activities of the company. He had fallen in love with a Chinese Malay woman, a seamstress, and had wanted to marry her, but there had been too many obstacles, the main one being Captain Light’s intimation that should he do that, he would have to forget a brilliant career, as a native wife would be a millstone round his neck and would put paid to his aspirations of advancement. That did not stop the woman bearing him a son.

Rob Rob did not remember the first three years of his life, but Godmother told him that his mother was a Malay princess who had died shortly after giving birth to him, and explained that he had been looked after by some native ayahs. When he turned four, he was sent home where his grandmother had looked after him and when she too died, he became the ward of the Duchess, although he did not live at Dunrobin, but with a cousin of Helmsdale-Robertson in Golspie. At an early age he was sent to boarding school in the south, but spent all his holidays at Dunrobin. The Duchess had children of her own, but she always had a lot of love for the young boy. The servants used to whisper that she seemed to love the young Etonian more than her own.

My dear Robert,

I have not had the pleasure of reading your letters in over six months, and hope that before long I shall receive a packet from Penang. First of all, let me assure you that Rob Rob is very well indeed; you will not recognise him, he has grown so much in the two years since you last saw him when you were over. His school reports have, as always been excellent, as you will have seen from the copy I caused to be made and sent to you. This being the long school holiday, he is here in Dunrobin, and has brought along two excellent friends from well connected families, I can assure you.

Dear George and myself, as well as children, all four of them, George, Francis, Charlotte Sophia and Elizabeth Mary, are also in perfect health.

I have every reason to suppose that Rob Rob will turn into a nice young man, but I believe that he needs a father’s guiding hand, specially when he is at such an impressionable age, if he is to avoid falling into one of the many traps awaiting to receive the innocents of this world in this day and age.

I have been concerned about an undesirable attachment he may have formed. You would be shocked to hear that the object of this unwelcome attachment is the daughter of a miserable crofter, an uneducated cowgirl. Since he allowed that girl to beguile her, he walks on air, spouts socialist nonsense, and spurns riches as being always ill gotten or undeserved, as if our ancestors accumulated their wealth by sitting in their armchairs, drinking whisky and stealing from the poor. I hope that this fancy will pass, as it usually does with young men of his age and temperament, but there is nothing like a father’s stern warning couched in conciliatory and loving language to make sure that it does. To this effect, I am getting in touch with my agent in London, to book him a passage to Penang after Christmas. I know that coming to see you has been one of his dearest wishes. He will naturally miss six months of school, but with his natural propensity for learning, I feel certain that with the help of a tutor whom I shall pick myself, his chances of a place at Oxford will not be compromised in any way. I will confirm the arrangements as soon as I have the details.

Last spring, I went boating on Lake Brora with the Duke, and I remembered the very same trip you and I took the summer before you were commissioned. Naturally I said nothing of this to George. It will be our secret.

I shall write a more detailed letter in autumn when I shall have more time. As you can imagine, at the moment, with three eager young men to look after, to say nothing of some developments to our system of tenancy which you would find tedious in the extreme, I do not have too much time to indulge in letter writing.

You will, as ever be in my prayers, dearest Robert, and I wish you happiness in your work in the colonies. I should be interested to know more about the experimental projects you mentioned in your last but one letter, I seem to remember it had to do with rubber or cocoa (or both).

Yours sincerely

Bessie

(Elizabeth Gordon)

Kitty was immersed in her specially commissioned Arabian Nights book when she heard the faint galloping sound of hoofs. She smiled at herself. I am absolutely besotted by that boy, she reflected, I hear him everywhere. But she was not too surprised a few seconds later to see Rob Rob approaching. He jumped off Silliboy and she immediately knew that he was very upset. She threw herself in his arms and they held each other tight for a few seconds, until she became aware of him trying hard to stifle his sobs. She pulled away in some alarm and immediately his tears began streaking down his face. She grabbed him and they both fell to the ground. She took his head in her arms and rocked him like a baby, kissing his tears, saying nothing.

‘They’re sending me away,’ he said finally, ‘they want to keep me away from you…’ She looked at him questioningly. ‘Godmother! She’s sending me away, I don’t know what to do.’

‘Sending you away? Where? To another school?’ He shook his head violently.

‘To Penang, to my father…’

‘But they can’t do that? What will happen to your schooling? Oxford?’

‘I am not sure, nothing is sure yet.’

‘Maybe you’re wrong, Rob Rob, maybe…’ her voice trailed off, and after a while she added, ‘but you will come back, won’t you?’

‘It means I won’t see you for a whole year, dearest heart,’ he wailed. She immediately burst out laughing.

‘A year is nothing, I will wait for you, silly boy,’ at which the horse, recognising his name gave a neigh of acknowledgement. She regretted using the word silly, but the reaction of the chestnut brought a smile to both their faces.

‘You will wait for me then?’

‘Of course I will.’ This time she said the word with emphasis. ‘I will wait for you till a’ the sea gang dry!’

‘Father might want to keep me there, but I promise that I will not let him. I will come again, my love, tho’ twere ten thusand mile.’

She smiled her gratitude at the man from Sassenach parts knowing the poems of their beloved Scottish bard, which were now so popular that even Highlanders recited them in English in taverns.

Kitty had always been aware of her sensual and passionate nature, and had always known that she would find it hard to keep her desires under control. Now that she had found the love of her life, she saw no reason why she should not do what had been foremost in her mind ever since she fell in love. The cows seemed to be looking at her, urging her on. Marigold even let out an encouraging moo. Yes, she would give herself freely to the man she loved, the only man she would ever love. It was a wilful decision, taken with complete lucidity. One did not become pregnant after just one act, she knew dozens of women who had been unsuccessfully trying for a bairn for ages.

She took his head and pressed it to her face, and kissed him on the lips, opening his mouth with her tongue, as if she wanted to get inside his body. Her body was pulsating and he was in a similar state of excitement. She felt his hardness against her thigh and smiled. He felt slightly embarrassed, and she teased him by placing her hand over this stiff presence, stroking it gently. It was obvious to him that she wanted to do exactly what he had been praying for. He, unlike the unsophisticated Kitty who thought that conception only took place after repeated intercourse, was well aware of the risks, but in the certain knowledge that he was going to come back for her whatever the obstacles, he let himself go. In any case he was in such a state that he would probably not have been able to stop himself had he wanted to. It was the same for her. She had discovered how to pleasure herself at an early age, but knew that there was much more to it, and now that the moment had arrived for her to experience the ultimate pleasure, she knew that no power on earth would have stopped her. Neither of them had had the full experience before, but when the moment arrived, they let their instinct guide them. To Paradise and Back! She thought. No power on earth can create a more delightful feeling, he felt. They lay in each other’s arms under the August sun, as contented as they will ever be in this life.

The poems quoted in this chapter are Shelley’s Ozymandias (presumably an early draft) and Robin Hood’s Golden Prize, one of the many traditional ballads collected by Francis James Child.