Chapter 17: Clearance

(Highlands, 1800s)

Helplessness, utter and absolute helplessness was the state Hugh was in. What Albert had told him was the saddest piece of news ever to come his way. The obstacles were too many and too arduous. What could he, to all intents and purposes, an escaped convict, do against the combined forces of landlords, their powerful allies in the government and the forces of law and order? They had all the cards and the tenants had none. No man to turn his back on a problem, he, but he prided himself that he was ever the realist. There are some battles one can never win, the dice are loaded against the poor. He knew that he would never be able to wean silly Kitty away from that toff who would bring nothing but shame and misery on the family. As he knew that one day John who was now working on the Caledonian canal, was going to leave for Canada or the Carolinas and that there was nothing he could do to stop him.

First their crops had largely failed, and famine was rearing its ugly head. Mam had a point, if God existed, he was not on the side of the poor. How can anybody fight a campaign against such heavy odds on an empty stomach? He had witnessed the rape of the gentle folks of Lairg, three hundred families dispossessed of their crofts, carted away like cattle to hastily built shacks on the northern banks of Loch Naver, with no means of feeding themselves, entirely dependent on the charity of the lairds and the church. The Cheviot sheep was everywhere, you could not sneeze without a droplet landing on one!

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Lennart Tange

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Lennart Tange

Hugh was torn between self-preservation and his determination to do what was right. He and his fellow crofters were under threat, and he was probably the only man around who had some experience of organising a movement to resist the onslaught. Could the so-called Improvement be stopped? Very probably not, it was like an avalanche slowly moving down the mountains, gathering speed nobody was going to stop it. You would end up get swallowed by its destructive power if you stood in its path. But does one have the right to just accept a calamity because the odds are stacked against one. He had once been a fugitive from the injustice of the strong and powerful, and if he raised his head in a crowd, his potential enemies might look more closely and discover who he was, but it would be cowardly to do nothing and watch his community decimated. For days he had been obsessed by that dilemma, and in the end he knew that he had no choice. He would be part of a movement working towards the best possible solution for his fellow tenants, but he would need to act cautiously and behind the scenes.

When a few potential victims of what was balefully looming overhead were invited to partake of some illicit brew at Tam’s, the conversation immediately turned to crofters and lairds, the hated Improvement and relocation. It was easy to moot the point that crossing one’s arms and waiting for the worst to hit you was not an option. Everybody agreed, and when Tam raised his tankard to this, Hugh, who was not devoid of cunning, chose his moment.

‘Since brother Tam is advocating that we stick together and plan a course of action, I think we should hear what he has to say.’

Tam could be quite astute, but he was guileless, and walked into Hugh’s trap.

‘Aye,’ he said, ‘we must be united, and… eh… plan a course of action.’

‘But remember, brothers, violence will get us nowhere,’ suggested Auld MacDonald. This had a mixed reception. Hugh decided that his best course of action was to listen and say nothing substantial himself. He noted that the determination of the folks was pretty solid, they all execrated the notion of relocation. He thought that Tam and Auld MacDonald would make reasonable negotiators, and mentioned this to Rab who was standing by his side. He was pleased when only a short while later, Rab repeated these same sentiments. One or two people loudly agreed with this, and before long it was clear that the two men would be the voice of the Movement. Hugh felt that he had a lot to contribute, but did not wish to be a kingmaker. He was a straightforward man, maybe not without guile but certainly devoid of malice, and he thought that a little scheming when it was for the common good that was perfectly acceptable. He quickly worked out his strategy: he would waylay each man in turn, and raise some issues with them and offer some advice stealthily, and immediately after the point had sunk in, he would say something like, ‘I think your idea about demanding to talk to Sellar with no preconditions is an excellent one, Mac.’ Or, ‘I am glad you believe that you should let it be known to the Duchess that the men all agree that she is fair-minded and will never do anything that openly went against the general interest, but perhaps you should also mention that people talk about her with great fondness for her past kindness in providing help in times of famine.’ And Tam would add, ‘But of course, Angus, of course I will say that, and refrain from saying that she was the root cause of the famine in the first place.’ Tam was clearly no fool. And the two men would have a good laugh. Hugh felt elated at being able to put his ideas across without raising his head above the parapet.

As Tam MacDiarmidd and Auld MacDonald’s leadership became more established, Hugh felt that his role in the proceedings had been kept well out of the limelight, and he felt empowered to give advice more openly, but he sometimes worried about those two worthy men shouldering the blame if things went badly. He gave the pair one piece of advice which they found particularly useful.

‘Put it to Mr Sellar and Mr Young like this: say you abhor violence and that you were finding it more and more difficult to stop our people threatening to set fire to the shepherds’ houses, but they were angry and you feared that you might not be able to stop a tragedy unless the Duchess and other lairds were more conciliatory.’

Tam and Auld Mac did their job very competently, and the upshot was that they wormed out some concessions from the lairds who allowed provisions for cattle to be purchased at improved rates. Further the tenants were allowed to stay in their abodes for a further six months, until proper accommodation was built for them in Caithness. But no power on earth would make the Duchess budge from her position that resettlement would be on a very fragile basis. She stood firm on her insistence that no leases would be accorded. Everybody recognised that this was a wicked strategy to ensure compliance with her every wish, that any recalcitrance however minor would be followed by instant eviction without recourse.

Then the worst famine to hit the Northern Highlands in man’s memory struck, and the men became disheartened. The 42nd Regiment was again deployed from Dundee, and the soldiers made their presence felt in order to intimidate the helpless folks under threat of eviction. The Duchess did not hesitate to break the word she had given to the people and ordered instant evictions, which were enthusiastically carried out by Sellar and his team. At first they allowed the evicted to dismantle their lodgings so that they could transport them wherever it was possible to rebuild, but there were instances of some dispossessed crofters coming back and rebuilding on the same site. It was thus that Sellar decided to put into practice his brilliant if sinister plan of setting fire to the crofts. He was quite enthusiastic about the use of force to evict his victims, and on two occasions people died.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Tiago Cabral

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Tiago Cabral

Hugh was in a state of deep despair when he heard of the death of old Mrs MacPherson who was over ninety, and senile. When he had first moved to Strathnaver from Fort Williams, she had been one of the first to help, with offerings of oats and potatoes, and looking after Kitty and John whilst the grown ups were busy settling in. Sellar’s men, accompanied by a handful of fierce looking men from the 43rd, had commanded them to move outside, and Sellar himself declared in his loud whine of a voice that he was giving them fifteen minutes to collect their possessions, and warned that his men had orders to set the shack on fire after that. The MacPherson sons, knowing that the factor meant business had quickly gathered their belongings and in fourteen minutes they were all out, the old lady leaning on the shoulder of her daughter-in-law. Sellar then gave a nod, and a man, making an apologetic grimace to the family took a torch to the wooden walls, and it surprised everybody how quickly the conflagration spread. The ninety-year old woman looked at it in amazement, utterly confused, then suddenly, freeing herself from her daughter-in-law’s grip, she shouted, ‘We forgot Mam inside… coming to help you, Mam…’ and screaming, she rushed into the flaming house with surprising nimbleness in an attempt to save her long dead and buried Mam. On the same day Hugh saw Kitty run to her Grandma in tears, and it transpired that she was pregnant.

John had not been gone a month when a penny post arrived telling the family how happy he was in Fort Williams, with a team doing maintenance work on the equipment. But from the beginning he understood that the dark clouds of downsizing hovered over those desirable jobs. The company was always short of funds, although the manager had assured them that any lay offs was likely to be short lived. It was known that the government in London was very keen for the project to go on, temporary hiccoughs notwithstanding.

Still nobody was too surprised when one afternoon, John arrived home unexpectedly, explaining that following the principle of last man in first man out, his services had been dispensed with. At first he said that he would be happy to work with his Da until he got the call to return to Fort Williams.

The boy had made some savings and was excited at being able to buy gifts to his loved ones. Even Da was forced to accept a new pair of boots.

The family soon gathered that the uncertainty in which John was living was not making him happy. Grand Mam was not too surprised when one day he spoke to her of his renewed interest in the Earl of Selkirk’s scheme, and the old woman did nothing to discourage him. She had heard that the Duchess opposed emigration on the grounds that she needed a good workforce in the Highlands in order to turn it into the new Lancashire, and this was enough to convince Grand Mam that emigration must therefore be a good thing. To Hugh, the Earl had no more business getting Highlanders to leave the home of their ancestors, than the Duchess the right to “Improve”. Why don’t they leave us alone, and let us get on with our lives like we always have?

‘My belief,’ said Mam, ‘is that the chance offered by the Earl is not to be dismissed lightly.’

‘Mam,’ Hugh had said sharply, ‘oor John has no intention of leaving for the Americas, don’t be putting silly ideas in his head.’

John said nothing, smiled enigmatically, but Kitty knew it there and then that no power on earth was going to keep her brother on these Scottish shores. Indeed it was not a week when John came home one afternoon, smelling of ale, and told them that he was due to sail for Nova Scotia in three weeks’ time. It was all arranged, he was travelling on the Moonglow from Cromarty, his passage paid by Selkirk’s organisation, and the shameless boy could not hide his joy at his impending departure.

Hugh stared at his son for a whole minute before opening his mouth. His face was red all over, and it was obvious to Kitty that he was on the verge of tears.

‘Does your family mean so little to you, John, that you could even contemplate leaving… your Ma… your family to go God knows where, and… and… be so pleased about it?’ John opened his mouth to protest but could find no words. Grand Mam tut tutted, and Hugh looked at her sternly, saying nothing.

‘Hughie,’ she said, ‘would you say I loved you any less than you love oor John here?’ He said nothing.

‘If after the Ross-shire Insurrection, you had been able to go to the Americas instead of facing a trial for your life, I would have been the happiest woman alive, even if I were never to see you again. Knowing that you were safe and well would have been enough for me.’ After a short pause she added, ‘When he is there he might look up his granda and his step uncles…’ she added to the amazement of John and his sister.

John and Kitty looked at each other, dumbfounded. They had often heard their Da called Hugh, but had obviously given it less attention than it deserved. They had heard about the Insurrection, but knew little about it, and neither could imagine that their father had faced a trial for his life. Martha noticed the consternation on her children’s face, and turned round to face Grand Mam, who immediately understood that she had just unwittingly broken the oath of secrecy. But she was defiant as always.

‘I know, I know… I shoudnae hae said that, I dinnae mean tae, but they are grown-ups now and need to know the family history… yes, your father led the Ross-shire riots and stood trial for his life in Aberdeen. He was found guilty of rioting and sentenced to transportation.’ She took a deep breath and told them the whole saga.

‘But… but Da —’ John was not able to finish the sentence

‘And his name isn’t Angus Smith either, he was born Hugh Breac Mackenzie… I’ve always hated the name Angus anyway.’

‘Children, you must know how dangerous it still is for your father if this story gets out of the walls of this house, even after all those years. If he is caught, this time it will be the gallows and make no mistake.’

‘We are not kids,’ they said together. John, on a sudden impulse jumped up from his chair and threw himself at his father and hugged him saying, ‘Oh Da! Oh Da! We never knew.’

Although Hugh had tears in his eyes and could not utter a single word because of the lump in his throat, Kitty knew that that was perhaps the happiest night of his life, his son’s impending departure notwithstanding. He gently pushed John away, but everybody, including the son could see that he would have dearly loved to hang on to the boy for another hour, but proud Highlanders did not hug each other. Martha grabbed John’s hand and led him to his chair like a blind man. Hugh cleared his throat and said, ‘John, do what you must do, as your Grand Mam said, the important thing is for you to do something of your life, never do anything that your Mam would disapprove of.’

‘No, Da, of course not.’ Kitty would have bet her life on this.

‘I am sorry John, I wasn’t thinking straight, your Grand Mam is right… I was only thinking of your Mam… you know how much you mean to her…’ and almost inaudibly he added, ‘to me.’

Could it be true, Kitty wondered, that she would never see her brother again in this life, the only life one had, according to Grand Mam. John on his part could not hide his impatience at the slowness of the day. He would leave Strathnaver in two weeks, and he had worked it out, fourteen days, three hundred and thirty-six hours, over twenty thousand minutes! Then six weeks at sea. He couldn’t wait to experience the sensation of finding yourself surrounded on all sides by the deep blue roaring sea, listening to the waves lashing against the bulwark, of being sprayed with invisible droplets of sea water. The fun of sailing will more than compensate for the separation from his loved ones. Of course he loved them all, he only wished that he had been a better son and brother, but he knew that in the eyes of Grand Mam he could do no wrong, although he supposed that the many stories she told them about this whinging boy in that country which was more north of the North Pole was modelled on him and meant to be moral lessons against selfishness and wickedness. I am not really a wicked person, he assured himself. If it’s true that one could make good money in the Americas, he certainly will not forget his family, he would send them money and whatever he could. Who knows, he may even be able to send for them.

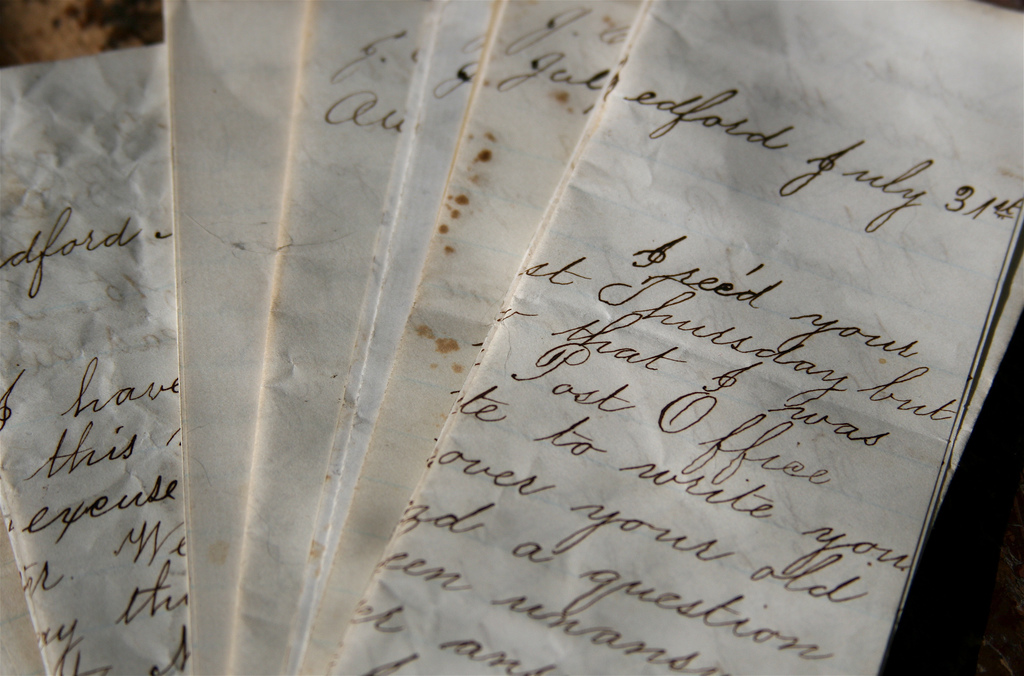

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Julien O

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Julien O

Suddenly there were only two days left for him to start on his journey to Cromarty, and he was filled with panic. He could not swim, what would he do if the ship hit an iceberg and sank? How was he going to bear the sadness of the separation? Could he change his mind? Da would like that, and Mam too. Poor Kitty! He had always been unfair to her, and yet she was so clearly distraught at the idea of his going away. No one can ever love you as much as your family. He doubted that if one day he fell in love and married some woman, she would love him as intensely as the family did. Poor Da! I never dreamt that he could have been involved in organising a riot against the lairds. What a crying shame that I have never really known my Da! I never knew that he was a hero, but I’ve always seen him act heroically all his life. He is a man of few words, and I will never have the opportunity of finding out more about him. And the poor man’s trouble isn’t over yet! Will he ever know peace? Already there are signs of another upheaval. That pestilential woman in Dunrobin wants more money in her coffers. She obviously does not care how much suffering she inflicts on the poor. What will Da do if he gets served an eviction order? Will he go to the coast and learn to become a fisherman at his age? Has he got the strength left in him to go kelping? What will happen to Mam, to Kitty? Suddenly he shivered as he thought of Da being involved in another movement against the lairds. They would be bound to find out who he is. No, John cried aloud, I cannot let them hang him! I must not be a coward and abandon him. Da who was outside heard him and came in. John was pale and was trembling all over.

‘What’s the matter, John?’

‘Da, I… I am not going to leave, I want to be by your side… I don’t want anything bad to happen to you… please Da, tell me you will not… expose yourself to any danger…’

‘Of course not, my bonnie boy, I am a cautious man… no harm will come to me, I promise you.’ He shook his head, the ghost of a smile on his face, and added, ‘Don’t be a softie, laddie.’

‘My mind is made up now, in any case, I am not leaving.’

‘Think of your future, laddie, you have a big future ahead of you, don’t waste it.’

But his mind was made up now, he was going to stay in Strathnaver and if the family had to go to Wick or Caithness, then his place was with them. Hugh tried to talk him out of this stupid resolution, but seemingly to no effect. Martha likewise had her say, and finally Grand Mam. His resolution to stay was unshakeable, he swore. Maybe later when things settle down, he said, he’ll think again.

However in the night, Martha and Grand Mam packed up his things, the woollen socks, hats and jumpers that they had knitted, the shirts Martha had cut and sewn by hand, the dry oat biscuits Kitty had baked for him, the bottles of illicit beer Hugh had bought from Ebenezer Reid. When they woke him up and he saw that everything was ready, he was relieved, for in the night his resolution to stick with the family had weakened, and he allowed them to talk him into pursuing the course he had been so keen on embarking upon a few days before.

The whole family went with him to Golspie by cart. Everybody put on a brave face, but John himself could not stop his tears streaking down his cheeks. They arrived at Golspie to find the boat to Cromarty was already loading. When Father and son hugged and kissed each other for the last time, he said, ‘Ah dear sweet John, so you are away to an unknown land. May God look after you and make you prosper.’ Even in that poignant situation Grand Mam could not stop herself murmuring that one has to look after oneself for God only looked after the rich. Hugh looked at his old Mam with loving indulgence. Then he turned to the boy and said those words he later wished had remained unsaid, as he feared that they would cause unnecessary distress to the boy.

‘Can it really be the last time you and I will touch each other like this, laddie?’ John was unable to stifle a sob, and the man who had defied the armed Cameron brothers broke down and sobbed like a child.

‘If you do meet your granda,’ Hugh heard himself say, ‘give him our love.’

Kitty was distraught at not hearing from Rob Rob. Could it be that she had been wrong about him? Grand Mam had warned her about those rich young men who wanted their wicked ways with peasant wenches, promised them the earth and then abandoned them to their fate. The besotted young woman would believe that lochs would freeze in midsummer before believing that her darling had been toying with her affections. She had always had a self-assurance uncommon in people like her, and concluded that the Duchess who had long arms must have connived with the Eton authorities and with the postal service in Sutherland to deviate correspondence between the two of them, to Dunrobin, not that this stopped her, every morning, from thinking that she would hear from her lover in the course of the day.

Martha decided that Kitty was not going to do any more heavy work in view of her condition. The pregnant teenager had protested that she felt fine and that the baby was not due for a good few months anyway, but Martha put her foot down. No lassie, you stay at home and knit things for the wean and read your books, we do not want you to take any chances. In any case, Hughie had got rid of two of the cows when he was unexpectedly offered a good price for them. Kitty was surprised that no one had been angry with her for what she had done. No one accused her of bringing shame on the family. She knew of girls in her position who, ordered out of the parental house had disappeared into the Edinburgh mist never to re-emerge. Strangely, Hugh even gave the impression that he was even looking forward to becoming a grandda.

What happened next was something nobody was prepared for. A few weeks later, Hugh had gone to Golspie and was drowning his sorrow in a tankard of ale at the Stag Heid when George the innkeeper asked if he had heard the news. What news? Don’t know how to put this, Angus. Put it in any way you like, George, I could not hear worse, the day. Ah but you can, Angus, didn’t your John go to the Americas on the Moonglow? Hugh stood up in panic, spilling his tankard. His body went as cold as a corpse, he did not need to hear more.

‘George, you are lying!’ He shouted, ‘You are a lying villain, how can you?’

Other folks rallied around, trying to calm him down. The Moonglow had indeed gone down off the coast of Newfoundland with complete loss of life. How right Mam had always been. How can a loving God inflict so much misery on the poor of this world?

When he got home, tears were rolling down his cheeks, and the three alarmed women rushed to him and Martha took him by the arm and asked him what had happened. It’s my fault, was all he was able to say. What’s your fault, they all asked, and he shook his head and kept crying. They sat him down, and waited. It took a long time for him to stop shaking and sobbing, by which time, the women had guessed the truth. But not wanting to tempt the devil, they maintained their composure, and waited for Hugh to spell it out for them.

‘The boy,’ he said, and stopped immediately, his speech shut out by new sobs.

‘The boy? You mean oor John?’

‘What happened to oor John?’

‘Da, it can’t be true, what are you saying?’

He made a sudden lurch towards Kitty, seized her forcefully, and drawing her to his bosom he hugged her, and suddenly calmed down.

‘Aye, Kitty, the Moonglow went down in a storm, and everybody’s drowned.’ Kitty pushed him away, angrily, and began shrieking, ‘No, it can’t be true, Da, you are lying, they lied to you, oor John can’t be dead he is only young!’ Grand Mam started sobbing quietly, shaking her head in disbelief. Suddenly Martha, who had never in twenty years raised her voice at her man, flung herself at her husband and with her clenched little fists started hammering the poor man on the chest, saying, ‘It’s your fault, Hugh Breac MacKenzie, it’s your fault! You had to go and attack those Cameron brothers and get us thrown out of our home… everything you do ends up in disaster…’ Then, God knows where she got the strength from, she took hold of him and shook him with surprising violence and said, ‘You think you are a big man, how come you could not stop him leaving?’ Kitty was going to pull her away from the helpless man, but Grand Mam stopped her, and raised her hands in a clear indication that she should let Martha say her piece. She continued talking incoherently, her words mixed with her sobs made gibberish.

When Martha had calmed down, she went and sat in a corner on the floor, her head between her knees, and she wept silently for her lost little boy. Hugh grabbed Kitty again and pulled her towards him.

‘Promise me it’s a boy you’re carrying inside you, lassie, we’ll call him John, promise me.’ Kitty smiled wanly and nodded sadly.

One afternoon, a few weeks after the Moonglow had gone down, whilst she was sitting outside the shack, knitting something nice and warm for the baby who was now due in a matter of days, Kitty saw the postie coming over. She was not yet ready to accept that Rob Rob had forgotten her and could not contain her joy, and shouted, ‘Grandma, what did I tell you? He’s written!’ Grandma was not even within hearing distance. The postie was out of breath by the time he reached the farm, and delivered a letter to Kitty, who was too excited to offer him a cuppa. She was surprised when she saw that it was addressed to Da. She was used to opening letters for the family, and she sat down, watched the postman disappear. Carefully she opened the letter, and recognised John’s scrawl.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY liz west

Photo Credit:

CC-BY liz west

Dearest Da, Mam, Grand Mam and Kitty,

First of all I am terribly sorry if you have had the pain of mourning my passing, but no doubt you will be pleased that I am still alive and not only well, but prospering. Let me tell you first of all that we had so many mishaps, nearly sinking with our leaky little boat, that when we arrived in Cromarty, the Moonglow had already left. So this explains how I am still around. Lord Selkirk’s agent arranged for me to travel on the next ship which left three days later. Our ship, the Highland Fling did not sink. We landed safely in Quebec and travelled mostly overland to Port Hope. I was homesick and felt lonely although I met many capital fellows during the voyage. I am now in Oxenham, Ontario. The Captain, my employer strikes me as the most fair-minded man in the whole world.

Dearest Da and Ma, and Grandmam and snotty Kitty, I worry about you all the time. I know how difficult life is for you, with threat of eviction hanging over your head all the time. You cannot fight the rich lairds Da, you do not have the means, the dice is loaded against the poor, Grandmam is right. If you allow me to give you some advice Da, the best thing you can do is to come and join me here. The Captain says he can use lots more people on his farm. The conditions are fair and square, and nobody treats you like animals. And it is a beautiful country, and I am sure you will never regret it if you come over. I am dying to see you all. Think of my proposition. I do not yet have much, but I will send you some money soon. If you decide to come over, the Captain has offered to advance the money for fares etc…

Your loving John, who is very much alive.

Kitty’s first reaction was to destroy the letter, as she refused to entertain the idea of the family emigrating to Canada. What would Rob Rob do if when he came looking for her and found her gone? Then she became so angry with herself she felt like smashing her head against a tree. How could she commit the mortal sin of depriving the family of the happiness of finding that their John was still alive? Oor John is alive, she started shouting to nobody in particular, dancing about, paying no attention to the baby inside her. It was Martha who first saw her in this state as she came in from the potato field. Kitty flung herself at her mother, shouting ‘He is alive, Mam, he is alive!’

‘Aye, but is he going to do the right thing by you? Is he coming over to marry you as he promised?’ Kitty laughed merrily.

‘Mam, I am talking about oor John! He did not drown, he is alive and well.’

Martha was too confused to understand.

Kitty, in spite of her condition, fairly carried Martha over to the shack, sat her down and sat at her feet, and read John’s letter.

‘God be praised!’ said Martha crying and laughing at the same time. Grand Mam came into the shack at the same time, and frowning asked, ‘Why take his name in vain?’

‘Oor John is alive and well, Mam, God be praised!’ Grand Mam could not believe her ears, and making her hands into raised little fists, she turned on herself in a spontaneous sort of comical jig.

‘So oor John is alive and well…’

‘He missed the boat which sank!’ explained Kitty.

‘The good Lord made him miss that boat,’ said Martha defiantly. Grand Mam nodded, then smiling almost in triumph, said, ‘If that was the Lord’s doing, then so was the sinking of the boat he missed, with two hundred dead, all sons of grieving mothers.’

It was Hugh’s turn to come in next, and he could not believe his eyes when he saw the women laughing and dancing around excitedly.

‘If you knew what I just heard, you would not be dancing about,’ he said with obvious disapproval. To his surprise this reproach rekindled the hilarity. He could not remember ever seeing the dour old woman so happy. He felt his anger begin to rise.

‘And if you knew what we just heard, you would join us, Hugh Mackenzie, instead of looking like you’ve just swallowed a mouthful of dung,’ said Grand Mam merrily. Martha went to him, took him by the arm, and told him the news. Hugh looked like he did not believe this, but the women were jumping about and looking so happy that he knew that it had to be true.

When the women had calmed down, he asked Kitty to read the letter to him. He listened to it attentively, and when Kitty had finished, he nodded gravely, and it was one whole minute before he spoke.

‘Since oor John thinks it’s a good idea, I think we had better take him at his word and go join him… it’s the only solution… I’ll look into it.’

Kitty was absolutely shattered, she did not wish to leave. What would Rob Rob do when he finally made it back to the Strath? Was there an alternative? Da had already taken the decision, and nobody would listen to her. She could not run away, where would she go? How would she feed herself?

‘What were your bad news, Hughie,’ Martha asked him softly. He shook his head sadly, but did not reply immediately.

‘They are giving out eviction orders… ours are surely due to come in a day or two.’

The straw to which Kitty had been clinging to vaporised into thin air, leaving her sinking in a bog of despair. How would she communicate with Rob Rob? Let him know where she was. Mr Shelley did not seem to have passed on her desperate message. But he was her only chance.