On that clear sunny afternoon somewhere in the Highlands, Katrina Crialese had no clear idea about the route she was going to take. Contrary to her nature, when travelling, she never made plans set in amber. She went where her fancy took her. She could start in a certain direction and then find herself changing it on a vague hunch. As long as she made it to Ullapool at some time, she did not mind where she went. Anywhere you went on this enchanted place was a treat. She had no idea that the Scottish Highlands were so magical. She still had a few weeks of freedom ahead of her before settling down in new surroundings and she had no anxiety about this. In her experience there had never been a problem with fellow academics, people speaking the same language, and no doubt fired by the same thirsts. She often heard negative things about a colleague, about people delegating work to juniors, or even doubts expressed about the complete authenticity of their papers, but she paid scant attention to gossip. If there was jealousy and back-stabbing, she was never the target of any, as far as she knew, and never in a million years would she say anything behind someone’s back that she would not say in front of them.

Having been born in Britain, she was always considered by the Italians as a glamorous Saxon and she thought that they treated her with more respect than she deserved. Having grown up in Italy and acquired a much-admired tan (although she knew of an Italian emeritus professor who whilst doing a Ph.D in Bristol in the seventies was told, Sorry, we do not rent our rooms to coloured people) and speaking perfect English, albeit with a slight Italian accent, she had acquired an exotic aura in anglophone circles, which she found pleasant to bask in. She had very little recollection of Dunstable where she had lived until she was four. Gliders? She planned to go have a look at it some time, now that she was going to be in the British Isles for a couple of years at least. She might look up granddad Rudi if he was still alive.

If Gina never tired of telling Katrina almost everything about herself, including bits that someone with her history might have been excused for keeping to herself, the young scientist, when not yet a teenager never had enough of her tales. Gina’s mother was born out of wedlock, she revealed without batting an eyelid. What’s wedlock? The little girl had asked. Look at it this this way cara mia, she had started, there are two types of bastards in this world and she had elaborated in details, to Maria’s alarm. After a while Maria, Katrina’s mother gave up trying to stop the older woman giving her daughter uncensored accounts of her life, in the knowledge that it would make not the blindest bit of difference.

The family farm in a village upon whose name no two families agreed,on the edge of Montepulciano, which was even then one of the most backward places on earth, produced far too little for a comfortable life. Wine, she told the wide-eyed toddler, was so cheap most people used it to brush their teeth with — those who bothered at any rate. They even gave it to the cows! Oh the fun Gina and her little friends had watching their drunken antics!

Gina’s very first memory was of her mother crying on the way home one morning after Sunday mass. She did not understand the reason then, but Padre Pietro had based his sermon on the theme of girls without morals who did not think of the consequences of their sinful folly, and everybody had turned round to look at her Mamma. This was a favourite subject of the holy man. When she was unlucky enough not to fall asleep in church, she would hear him tell the congregation how girls followed their mother’s example as surely as water flows down the ditch that’s already there. Gina suspected that whenever he was too drunk to prepare a fresh sermon on Saturday night, he rehashed that old theme.

She had never felt at ease in that place full of morons, and as the farm was not doing at all well, she decided to leave home, doing a variety of jobs as laundress, maid, kitchen hand, flower seller among others, sending a large fraction of her meagre earnings home.

‘You name it, ragazza, and your grandma has done it,’ she told Katrina who never failed to detect some pride in the assertion.

During the war years, she found work quite readily and ended up working as a kitchen maid for the British troops after they arrived in Monte Cassino.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY genevieve

Photo Credit:

CC-BY genevieve

They had set up camp in the Trocchio Hills, and hired a small number of locals to do various odd jobs, as there were not enough auxiliaries. When they were available, they were usually privates from the colonies like Ceylon, Fiji, British Guyana, Mauritius, Trinidad. They wore uniforms but they did not carry guns and were not trained for military action.

‘Most girls dreamt of attracting the notice of some blue-eyed Yorkshireman, a Gary Cooper or a Jean Gabin, and would have nothing to do with the darkies,’ she said. Not her! There were so many people she knew that she could look down upon for their lack of charity and other real failings, so why pick on skin colour? In any case she always thought that there were some shades of brown which were was much more attractive than pasty white. Many of her fellow workers thought her a proper hussy for befriending the colonials, even if she spoke no English and they no Italian.

Then Prakash entered her life. He was small and thin and looked like a hungry teenager, and she thought that he was the most beautiful young man she had ever set eyes upon with his shiny brown skin. ‘You are such a sharp little missy, you must have noticed that I always put the same quantity of milk in my coffee, no? Today I will tell you the reason: because that was exactly how my Prakash looked, the only man I’ve ever loved.’ He had peerless dark brown eyes, long eyelashes and the most perfect nose. And he began to chat her up. ‘His voice was like music I tell you, and his laughter — why, cara mia, after all those years I can just close my eyes and hear it ring like little bells.’ He spoke little English and less Italian, but that did not stop him trying his luck with the girls, oh yes, all the girls. He was irrepressible. Somehow he managed to make himself understood by using words from his own language, adding an “o”. The first thing he said to her was “to bello,” then correcting it to “to bella mo to aimo”. He came from Mauritius where they speak a patois of French. It did not take a genius to make out what he meant, nor what he was after, Gina explained. She never made any bones about her past history, not stopping at giving her granddaughter graphic details, including how they did it the first time, clearly relishing the telling.

Whenever they had some free time, they met, sat under a tree or went for walks on the hills overlooking the villages, smoking, talking gibberish before they developed their own brand of esperanto. But more than anything they laughed. It was the laughter which cemented their relationship. ‘You know, cara you can build the best possible relationship with a man based on laughter.’ And of course the inevitable happened.

“‘Why would I not give myself to him?’ She said flinging her arms up, ‘Why would I deprive him of what I had generously given to others before him? I was unmarriageable anyway! So why deprive myself of something I wanted with all my heart? I might be lots of things but hypocrite I am not, Katia mia!’ Yes, it was a moonlit night, and they had arranged to meet behind the kitchen. To be honest, she could not remember the sex, only the smell of decaying potato peelings. Truth is, she confided, one does not remember the sex, only the after-sex glow… like food, you remember it was good, but not the taste. You will understand later, she assured her pre-pubescent granddaughter.

He claimed to have fallen in love with her and wanted to marry her. He showed her a photograph of his family home and promised that she would live like a princess on that paradise island. She thought she was too clever to fall for Prakash’s talk, but he was a fine talker, and she realised soon enough that she was smitten with him. She loved listening to the stories of his childhood in Mauritius, of his ancestry, the stories his parents had themselves been told by their ancestors, which had survived many generations. He had an excellent memory and so was able to recount the histories of his ancestry. Gina had an excellent memory too, and she would later tell Katrina everything she remembered.

She was becoming starry-eyed about the notion of going to a foreign country with a brown man who had promised him that she would be treated like a queen by his family in their stupendous mansion. One day, when you see that film, Son Of The Sheikh, with Rudolph Valentino, you will understand what I am talking about, she told her grandchild. However the moment she had become responsive to the idea of marriage, he started having second thoughts. He was not dishonest, she told Katrina vehemently, but it had dawned upon him that there would be too many obstacles in front of them. To begin with they were in the middle of a war; where would they find the money for the passage to the island? Once they arrived on the island, where would they live? He admitted to her that the mansion he had shown her was the Plaza Cinema in Rose-Hill — not that she had completely believed the tall tale initially. In the sort of house he lived in, the roofs leaked, the floors were cemented with cow dung, they had no electricity, did not even have proper toilets, just a hole in the ground. In our little village outside Montepulciano, we slept next to the cowshed she had countered. Then he declared that his people would not take kindly to his marrying a foreigner, a Christian. He was not only expected to marry a good Hindu girl, but one from the same caste.

He told her how his ancestors had arrived in Mauritius in the early nineteenth century with just the rags on their backs, having mislaid the head of the household on the way. This had not stopped his great great how ever many great grandmother from working her fingers to the bones, and ending up making a fortune, owning hundreds of arpents of sugar-cane fields, houses and stocks and shares. Only his father, the grandson of the matriarch had done the inexcusable, running away with the daughter of an ex-slave, a black African, and had been disowned. So, he had to admit that the stories he had told her about his family were a bit exaggerated — to the extent that hm… hm… they were in fact all lies. He had not inherited anything, and his family had remained poor. But he had sort of inherited the most valuable heirloom, a gold earring. Actually Prakash admitted that nobody gave it to his grandfather. When he the family banished him, as he knew where his grandmother kept it, he simply pocketed it as his due. Yes, just one of a pair. ‘You’ve caught me looking at it, but I never wear it.’

By now, she was completely besotted by her brown man from the Indian Ocean, and believed that when you are in love, all those obstacles that Prakash mentioned were minor irritations that could be brushed away. Gradually the young private caught some of Gina’s optimism and made up his mind that they were going to marry at the first available opportunity and tackle the obstacles as and when they arose. The fact that they had found each other convinced them that they were born lucky and for such as them, no difficulties were insurmountable.

But the war was still raging on, with all its uncertainties. The Germans had rallied after initial setbacks. Then out of the blue, they decided to retreat, leaving the Allies free to attack the Gustav line. Then General Lucas ordered his regiments to move. ‘I am not stupid, I listened and followed the development of the war, you know.’

She saw her lover for less than fifteen minutes before he was due to leave with his company. He was in such a state, trembling all over, trying so hard not to show her his tears. She knew there and then that it was the last time they would see each other. He had no idea where they were going. She knew that he would have tried to contact her, but was unable to. Neither were great writers. As he was leaving, he pressed his most valuable possession, the earring into her hands. ‘So you will never forget me,’ he cried. Even if they took her brain out she cannot forget that lovely man! Prakash will always be her first love, and her most treasured possession was a badly faded photograph of the two of them taken by an English private with his Brownie camera. She proudly showed it to Katrina, and she dutifully went through the motion of admiring the pair, but in fact one could hardly recognise anything. Of course she never told him that she was carrying his child — Katrina’s mother Maria.

‘What about the earrings, Grandma,’ little Katrina had asked, ‘why don’t you wear it?’ She had cackled merrily, ‘Do I have only one ear? How can I wear one earring?’ And she promised that Katrina would have it on her eighteenth birthday.

Katrina had always felt very close to that mysterious soldier, and as the photograph revealed next to nothing, she felt free to imagine him as Gina had described. It was this man who was her grandfather, and she was sure that he was no wife-beater like Rudi was. Might he still be alive on his island? Was he still in Dunstable?

Gina went back to the village to deliver Maria, and was surprised when Papa and Mamma did not throw her out. The baby was darker than the other little girls in the village, but although some people whispered wicked things behind their backs, she grew up into a normal hard-working peasant girl who could hardly read and write. Maria, her sweet, prudish lovely self-effacing mother. The fact that Katrina seemed to love Gina more, did not mean that she was indifferent to her mother. She had a different personality, she was more serious, vulnerable, not much given to laughter, but she respected her and admired her more than she knew.

‘Your other grandfather Rudi,’ she told Katrina, ‘said that he had been an Ukrainian resistance fighter against the Germans, but he never showed me no papers to prove that. One thing I can tell you though, Katia cara, he did not act like no war hero.’

He had spent the last days of the war in Istanbul, doing what, he never told Gina. He went back to Kiev when it was all over, but could not fit in. He thought they owed him a job for fighting the Germans, but there were no jobs. When he heard that there was work in England, he decided to take the plunge.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA NottsExMiner

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA NottsExMiner

The new government had promised to build new homes to replace those that had been destroyed by the Luftwaffe, and there was a huge demand for people to work in the brick and cement factories. He came to Bedford to work for the Marston Valley Brick Company where most of the work force were Italians who had been encouraged to come over in the mezzogiorno, with their passage paid, hostel accommodation guaranteed, usually on the Midland Road which would soon be known as the Via Roma.

The Italians tended to mix only with people from their own villages, and avoided other Italians, but funnily they had no such reservation when it came to Poles and Ukrainians. Why they took Rudi to their bosoms, Gina would never understand; it was certainly not for his charm.

Rudi easily made friends with some boys from Chianciano and was soon able to string together a few words in Italian, but he never spoke about the war. He helped build the Santa Francesca Cabrini church and developed a taste for pasta. After a year or so, Giuseppe, Aldo and Roberto, who were cousins, his three best friends decided that as they were earning good money and were in a secure job, it was time to find brides for themselves and that was where Gina came in. Rudi would have liked a bride too, but he hardly knew any girl. The lads then revealed that they were going to send for brides from their village. Their folks at home would make sure they chose good women with strong haunches and big tits. And if you want to, Rudi, we can ask them to choose someone for you too, they offered.

Ravaged by the war and by Mussolini’s excesses — Gina never understood how that flat-headed bastard had come to power — the country was on its knees. What had Italians done, she asked the little girl, that we deserved leaders such as il Duce or Il Divo? Anyway, most men were unemployed, unable to support wives and children, and those who had jobs had their pick of the girls. As a result, there were plenty of young Italian women who were less marriageable, for a variety of reasons, who would be willing to go to the end of the world to find almost any husband.

A few months later, four fresh but slightly shop-soiled peasant women arrived at Victoria Station in London, among whom Gina, with what reputation that she had acquired in the village — totally justified, she assured Katrina.

‘If I was a man, I certainly wouldn’t want a woman with a bambina,’ Gina said.

Anyway, three of the women were from Chianciano, and as the families had not been able to get sound local women, they had agreed to extend their horizons and go to that village without a proper name outside Montepulciano and found her. Maria was left behind with Gina’s mother for the time being, but Rudi knew of her existence and he had said it did not matter. There was an understanding that Gina would go fetch Maria at some point.

At first they were happy enough. She found him austere and humourless but soon enough began having doubts about the wisdom of the union. He seemed to be living in the past, and often had nightmares. Sometimes he would wake up in a sweat in the middle of the night, and when she pressed him, he would talk about Babi Yar and admit his part in the massacre, but spared her the details. He never laughed and rarely smiled, and complained about everything. But she was used to hardships, and was willing to put up with him. She loved to laugh and tell stories, and nothing he could do would change that. If he likes to sit and sulk, she had thought, he was welcome to it, but do it on your own, man! He rarely spoke about his Odessa days and she only heard about it from the girls who themselves heard about it from their husbands, to whom he would tell everything when they went drinking. Still, he was quite a handsome man with bluish-grey eyes and blond hair, and people who did not know him all told her how lucky she was to land herself such a catch. Yes, she had thought, if he had been a fish, he would have had the distinction if being the first blue-eyed fish.

Only a few months after their marriage, however, he began complaining that with a wife who did nothing he was hardly able to save any money. Contrary to his expectations, Gina greeted this news with relief. She was many things, but work-shy was not one of them. So you want me to go work? Why you no say so? I’ll find myself work if that’s what you want, you blue-eyed fish. Meltis was always looking for women workers, and she got herself a job with them. The pay was not much, but the combined salary was enough for a comfortable living, and they were able to save ten shillings every week. But the very best thing, she said, was that they could eat all the sweets they wanted. The broken bits that could not be sold.

‘Did I tell you that as a child, I never had any sweets, cara? So you see, I had a lot of catching up to do.’

She became the most popular woman with the neighbourhood’s children as well.

One day, out of the blue he brought up the question of little Maria.

‘What sort of woman are you?’ he asked, spitting on the floor, ‘having a little bastard like this. How many men have you fucked? What possessed me to marry a whore like you, a woman who was not a virgin? Who had fucked every soldier on the front’.

‘You no spit on floor!’ she screamed at him. She did not know it then, but he was already humping his best friend’s wife.

The war hero sprang up, threw himself at Gina and slapped her with the back of his hand. She reeled back with the force of the hit and banged her head against the wall. Whatever hope she had entertained of falling in love with the man one day evaporated on that night, like water poured in a hot pan. It took one slap. A man slaps you, cara, slap back, you are fit and strong. Anyway, she was trapped and there was no way out. She did not know how to get out of the country, but here at least she had a job. She would put up with him for the time being, she thought, and bide her time. One day she might end up sticking a knife in him, but not just yet. As a small child, Katrina was quite surprised to hear her grandma say things like how much she hated it when he demanded sex. Yes, Gina said with a shrug, she had to submit herself, and allow herself to be humiliated. It was a man’s world. How she prayed nightly that she did not become pregnant again.

To her surprise, one day, after he had been drinking all night with the cousins Giuseppe, Aldo and Roberto, he called her, and said that if she wanted to go collect Maria, that was all right, adding, ‘But don’t expect me to pay for your tickets.’

So she went with Sofia and Assunta who had also left their babies behind, and she came back with Maria. She had fully expected Rudi to ignore her little bastard, as she herself constantly and lovingly referred to her, but to her surprise, he took a shine to the little girl, and the two of them have always got on quite well. This made the relationship slightly more bearable to her, and a year later, Uncle Vittorio was born.

Katrina was very fond of the mentally handicapped uncle. He was sweet, always smiling. People think of them as unfortunate, but Zio was the happiest man she knew, loving his food, the sunshine, music and laughter. Nothing in the world gave him as much pleasure as to fart loudly in company, and laughing himself silly afterwards. Once he realised that the boy was not normal, Rudi lost interest in him, but he was never nasty or mean to him.

When Mamma was twenty-two she married Papa, second born son of Giuseppe Crialese, son of Rudi’s friend, although he was a couple of years younger than her. They had grown up together, with Maria treating him as a younger brother, but at an early age they both knew they were made for each other, and the relationship changed. Neither had done well at school. Papa got a job as a waiter at the Arrivederci near Bedford Station, but had hopes of becoming a chef; Rossano the proud owner encouraged him to go into the kitchen and learn. Maria trained to become a hairdresser. Katrina was born two years later. She remembered that they filled the house with toys that, to Mamma’s chagrin, she had little interest in. She was always bookish; when she was four, Papa was made redundant. People could no longer afford going to the restaurant. For a while the family survived on Maria’s meagre earnings, seeing that even the recession could not stop hair growing on peoples’ head. Then Papa got a job at Vauxhall’s in Dunstable, and the family moved to a rented flat near the Downs. Giuseppe was never happy cutting plastic foam to make car seats, when he dreamt of carving meat, fish or poultry, and when because of the recession, they cut the working week to three days, money became even scarcer. Katrina remembered the change in the atmosphere at home. In Bedford, it had been laughter and joy, but in this strange place it was long faces and sulks all round.

Gina had wanted out of her miserable life with Rudi almost since the first day, and as luck would have it, her only remaining brother who lived in the family farm in Italy died, and she was his sole remaining heir. When she said to Rudi that she was going home, he shrugged and said nothing. He was neither upset nor pleased. When the time came for the departure, it was done without acrimony and without tears. The two of them parted, and neither demanded that the other wrote or kept in touch. She told herself that she would send him a Christmas card every year but never did. They did get his news from Auntie Assunta who wrote two or three times a year. They later heard that he had moved to Dunstable too.

Katrina had been looking forward to start going to Icknield Primary when all of a sudden Papa came in smiling one day and said that they were all going back to Italy. She remembered the exact words, ‘We are going back home to Italy.’ Giuseppe had had never been there, nor had Katrina.

‘Zio Enrico has found me a job as waiter in Siena, we are all going back home to Italy.’ Mamma dropped a cup of tea that she was holding and threw herself at him, grabbing him by the neck and kissing him full on the lips, something she never did in front of her daughter. In the beginning they would stay at the farm with Gina, and Papa would cycle to Siena to work. Maria hoped to make the farm produce a few marketable products like cheese, butter, eggs and tomatoes.

Katrina had always thought that home was Bedford or Dunstable, but she had no difficulty accepting Gina’a little village. Maria and Giuseppe knew just enough Italian to converse with each other, as Gina had insisted on speaking Italian to anybody who had the faintest Italian connection. Even Rudi ended up with a good grasp of the language. If he had not seemed upset about Gina leaving, he was clearly sad to lose Giuseppe and Maria of whom he was very fond as well as the handicapped Vittorio. The latter did not seem to care.

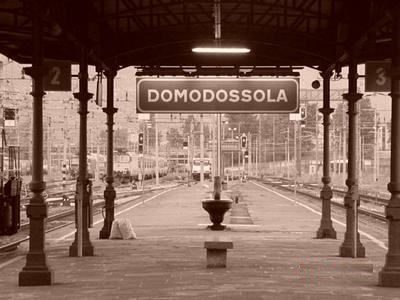

The four year old girl remembered the journey on the Orient Express, the night train to Dover, the ferry across the channel at dawn, and the excitement, the noise, the shoving and the pushing, everybody making a fuss over Zio Vittorio, and him enjoying every bit of it, even if he did wet his pants. The moment the train arrived in Domodossola, she understood what they had meant when they said, “We are going home!”

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Carl Rogers

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Carl Rogers

She loved the village, the open air, the fields, the woods. She loved the pigs, the ducks and the goats. She loved the smell of manure in the morning, the cows mooing in the distance and then there were the bells tinkling merrily. She loved the simple kind-hearted peasants. Papa had promised Gina that once he began to earn serious money, he would buy a cow or two, as an investment, and true enough, in less than a year they indeed had two cows and a bull on Gina’s patch.

She had loved her little school and was surprised when Signorina Lumini told Mamma that she had a seriously clever little girl who would go far. In her whole career, she said, she had never come cross anybody who was so bright and so hard-working. She should go to university, Signorina Lumini had said, and everybody wondered what a university was.

Papa ended up by achieving his life-long ambition of becoming a chef. His next ambition was to own his own restaurant one day, a big place in Siena or Florence.

After primary school, they sent Katrina to Scuole Medie in Siena where she did brilliantly, and finished her secondary education at the Liceo Scientifico. Then Bologna university, followed by a scholarship to Harvard.

Photo Credit:

CC-0 clarissavannini860

Photo Credit:

CC-0 clarissavannini860

Nobody ever saw Rudi again, although Gina’s friend Assunta sometimes wrote to say that the old man was well, and was living with a Polish widow in Dunstable.

‘He’s found himself another punching ball,’ said Gina.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P.