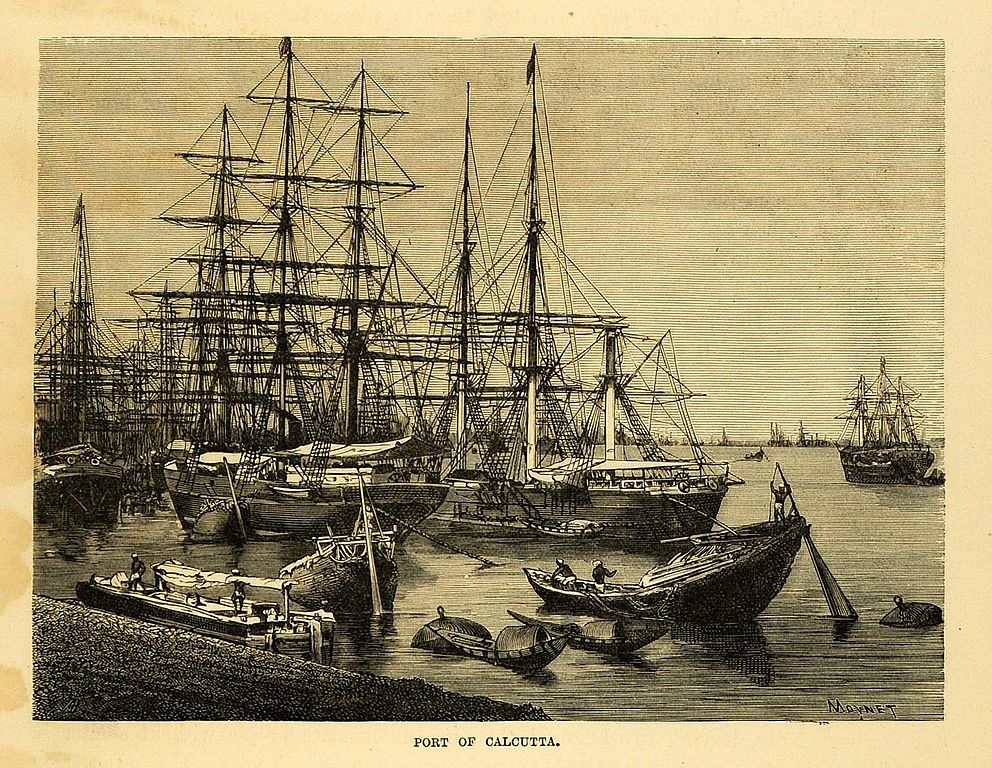

Book 2 Chapter 4: Leaving Calcutta

(Calcutta, India, Late 1840s)

When Jayant reappeared alone some time later, Shanti was filled with an inexplicable hatred for the young man, as if it was all his fault that he had not found Raju. She turned her head away as he began explaining that he had been unable to locate her husband and the girl because the crowd was much denser than he had imagined. She was not listening, and did not hear him bemoan the fact that it had been hardly possible to inch yourself forward one step without treading on someone’s toes and earning a rebuke. But I am sure that it was them, he said, shaking his stupid head from left to right. Shanti went pale on hearing this, and her whole body became cold. Were it not for the lump in her throat acting like a barrage, her tears would have burst through with a force that would have made them gush out in a flood of despair. She began to panic. The little boy noticed her mother’s state, and began to cry, kicking Jayant angrily when he offered to pick him up. She was only able to keep an appearance of calmness because she knew that she had to be strong for Pradeep, but after taking in a few deep breaths she regained some composure. The friendly auntie engaged her in conversation and that seemed to keep her mind off her main concern. She realised that when one is in turmoil and puts a bold face on things, stopping one’s tears by a superhuman effort of will power, the body still finds a way of reacting, and in her case, she noticed that her whole body was shaking like a leaf in the breeze beginning to build up before a storm. She tried to divert attention from her trembling hands by holding one in the other. The apprehension grew worse by the minute, but Jayant thought that she had succeeded in getting a grip on herself. Things became much worse when an official appeared unexpectedly and announced that passengers travelling to Mauritius on the Startled Fawn should proceed to the Harbour Office immediately. But I can’t go without my man and my little girl, she screamed at the friendly woman by her side.

‘But daughter, if your brother says he saw him in front, then if you don’t go, and your man and little girl get on board —’

‘But what are you saying, Chachi?’ Shanti snapped angrily, ‘my husband will never leave without me.’

‘Look,’ said Jayant calmly, ‘if he is ahead of us, he will surely get on the boat knowing that we can join him, what will happen if he gets on the boat and you… we don’t?’ Shanti’s dormant hostility towards Jayant nearly broke its leash, but she managed not to lash out. It was as if he had purposely failed to find Raju, but she knew that he was right. The friendly woman nodded at Jayant’s words, to show that she thought that he had a point.

‘But suppose you saw wrong, that the man you saw with a girl in a blue dress was someone else?’

‘Then you and I will go to Mareeshush without Raju, and all my sinful dreams will come true,’ Jayant thought, for he had always been half in love with his best friend’s wife. Instead he said, ‘Arrey, how can Bhagwan permit the two of you to become separated?’ The level-headed woman surprisingly found that thought very comforting. Indeed, how can Bhagwan play a trick like that on poor innocent souls like themselves, who had never harmed anybody? Jayant was not so stupid after all. But the latter was thinking that the same Bhagwan did allow the waves to gobble up his Ma and his Pitaji. It pained him to realise how love for one person could make you immune to the suffering of the rest of the world.

Photo Credit:

Unkown (Copyright expired) 1874

Photo Credit:

Unkown (Copyright expired) 1874

When after an eternity their turn came, they calmly inched forward, entered the makeshift shack that served as the Harbour Office, and Jayant tried to explain the situation to an impatient and unresponsive Mr Chatterjee the clerk. His Angrezi boss, Mr Delahunty enquired what the palaver was all about, and the Bengali clerk explained that the family had become separated, which made him burst out laughing.

‘Tell the Bint to go to Lost Property then, Chatterbox,’ he screamed joyfully. Chatterjee laughed immeasurably at his boss’s joke. He did not think the appellation Chatterbox was in any way derogatory, and preferred to think of it as a mark of affection.

‘What’s the cove’s name?’ asked Delahunty, and Jayant replied, Rajendra Parsad Varma, and the Angrezi scanned a list, mumbling some names until he landed on a Rajendra, nodded and said that he fellow had been processed already. Shanti sighed with relief, but immediately wondered about the girl. She rather rudely pulled Chatterjee’s sleeve and asked about the girl, ‘Was my little girl with him?’ to which the self-important clerk, offended by a peasant woman treating him with such lack of respect, replied testily, ‘Yes, of course, now get a move on, we don’t have all day.’

They were shoved towards a small door into an open veranda, joining other folks waiting to board the barge. You are so stupid Shanti, obviously Raju would not have left the girl behind, she scolded herself. The moment they had climbed on the barge which was about to leave, Delahunty, looking at the list of names, scratched his head.

‘I say, Chatterbox,’ he asked suddenly, ‘did that cove say his missing friend was Sharma?’

‘Yes, yes, sahib sir, Varma… I think… no, no… Sharma, yes, yes… quite very definitely Sharma.’

‘Good,’ said the Englishman, ‘there is a Sharma here… we would not wish families to be separated, would we, Chatterbox?’ adding, ‘my good action for the day, eh.’ He had stood up and taken a couple of steps towards the privy, when the clerk spoke.

‘This Varma chap, sir, he had a little girl with him, didn’t he?’ Chatterjee asked. Delahunty made a grimace and pursed his lips, clearly not remembering, but with a shrug, he said, ‘Yes, I think so…’ My good action for the day, thought the Bengali clerk.

When they clambered on board the barge, Shanti became very agitated at not finding Raju there, but at a short distance down river, there was another similarly cram-packed craft slowly moving towards the Startled Fawn, and the friendly woman who happened to be by her side nodded wisely, ‘He must surely be in that one, you’ll meet on the big ship, you must have faith, Bhagwan knows what He is doing.’ Yes, chachi, he must be, said Shanti.

Having survived the walk up the rickety steps and made it on board, Shanti, undaunted by the mass of people rushing in all directions, looking for relatives or misplaced possessions, began a frantic search for Raju, leaving Pradeep in the care of Jayant, and when the brig began its slow descent down the Hoogli, she became frantic, as she knew that now there was no going back. Jayant kept following her, carrying Pradeep on his haunch, telling her that Raju and Sundari were surely somewhere on board, and that once everybody had settled into the routine, they would suddenly appear. The deep resentment which had built up against the devoted family friend since their arrival in Calcutta was fast reaching its boiling point. Didn’t he swear that he had seen her husband and little girl in the crowd ahead of them? May Bhagwan stop her pushing him overboard if he continues annoying her! That idiot smiling like a half-wit, swinging his head from one side to the other, who cannot tell green from blue!

She kept pestering everybody with questions. Had they seen Raju? The little girl? At first people were sympathetic to her plight, but as everybody had their own problems, it did not take long for them to become irritated by her. She began pulling her hair out, screaming that she wanted to be taken back to the harbour. The other travellers began to get seriously uneasy and complained to some officers about this mad woman who was spreading panic and despondency on board in such a stressful time. Pradeep, seeing his mother in a state he had never known her to be in, began to cry and throw a fit. Finally an Angrezi officer, accompanied by a Bengali kitchen hand appeared and Shanti explained. The Angrezi was not impressed, but assured her, that her husband was surely on board, where else could he be? Under British rule people did not simply disappear, eh what! The Bengali man dutifully translated. He then solemnly warned her that unless she calmed down, he would lock her in a dark room below. If you do not calm down, the Bengali hand translated, the Angrezi man will throw you and your little boy overboard.

They were packed very closely in the holds. The men separated from the women. There were quantities of things scattered all over the available space, and on top of that, people were unable and unwilling to stay in one place, which made circulation next to impossible. Thus the devoted Jayant took about an hour to go backwards and forwards from the men’s quarters to the women and children’s, looking in vain for Raju. The cramped conditions were such that once seated, people could hardly move. The moment they had been allocated their spot, an area no bigger than a small cot, tired from the waiting and the hot sun, they were overwhelmed by the smell of sweat and apprehension filling the atmosphere. Then people began to suffer from sea-sickness and the vomiting never stopped. Often the bad odours were so nauseating that they caused more vomiting, which established an unending cycle of gut-churning abomination which was to last until the very end. Nobody got used to this putrid vomitous atmosphere. Another huge problem was the lack of toilet facilities. The passengers were given buckets, and although there was a torn curtain in a corner, they had little or no privacy. The pitching and tossing of the ship caused spillage, and no matter how much sea water was used to get rid of the filth, the odours persisted adding to the hellish mix already prevalent. Many years later, the people who survived the crossing would remember it vividly.

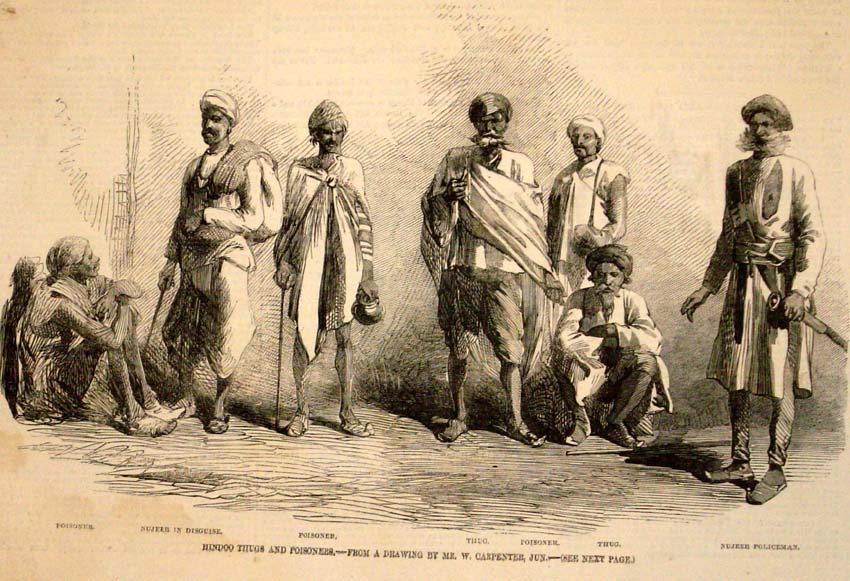

Soon the whole ship had become aware of the disappearance of Shanti’s husband and child. Most people were quick to express sympathy and say something comforting, but these produced little effect on her. The words that did produce an effect, were, unfortunately, far from consoling. An old woman from Orissa came to her, and shaking her head said that there was no doubt that thuggees must had seized her husband and child.

Photo Credit:

W Carpenter, 1857 (Public domain, copyright expired)

Photo Credit:

W Carpenter, 1857 (Public domain, copyright expired)

‘Arrey, didi, what are you saying? What are thuggees?’ And the thoughtless woman told her of those sinister individuals who were always on the lookout for innocent victims to kidnap. She explained that she knew all that because there were some men from her village who had been snatched by thuggees. Shanti was too stunned to respond, but although she was hating the woman for telling her all this, she was very keen to learn more. They go about in small teams, the woman from Orissa said, and one of them, an expert danta thrower aims a small thick stick with force at the ankle of a prospective victim, who when hit, falls on the ground, incapacitated, whereupon the bandits seize him, take him to their den, torture him, and finally offer him as a sacrifice to the Goddess Kali.

‘Arrey, what are you taking about? People don’t harm little children, my husband is with my daughter —’

‘We know the Goddess has special love for little children,’ the woman from Orissa said sadly, ‘which is why she specially values the sacrifice of little children.’

She decided not to believe the scaremonger, but she would never again have any peace of mind.

Every night she would lie on her mat tossing, unable to sleep, and when she did, she was tormented by nightmares. They were always the same. Raju would be in a pit, blood dripping from all over his body, but he was smiling happily, and she would bend down and give him an arm to pull him up, but however much she tried, she could never reach him.

For the duration of the voyage Shanti was like a living corpse. The other passengers having problems of their own, half of them suffering from acute sea-sickness, ignored her completely and only the devotion of Jayant kept her and Pradeep alive, forcing food inside her, fanning her, or applying compresses of cold water on her fevered brow when the heat became unbearable, all this doing nothing to mitigate the deep resentment she felt towards him. In the first week there were a dozen deaths through dysentery and diarrhoea, and the situation did not improve as the voyage progressed. Everyday someone died of some unidentified sickness, and got unceremoniously thrown overboard.

They had been at sea for just over a week, when the storm hit, and as the ship began to roll perilously, people started screaming in the certain knowledge that the end was nigh. Some women were shouting that it was their men’s fault, that they had said that they did not want to go, but the men always think they know best. The men in their quarters were blaming their women. They would not have left their homeland but the womenfolk were never contented with what they could bring home. People got tossed all over the place. Not my fault, sister, it’s the storm. No, you could make a little effort, you are going to smother my little boy. You are squeezing me to death. Many got hurt, tempers became frayed, and fighting broke out among the men. Six people died of broken skulls as the force of the storm hurled them across the hold to the hull of the ship, and were buried at sea. Many more became seriously sick of a variety of ailments, some of whom inevitably passing away.

How she and Pradeep survived, Shanti, haunted by nightmares every night, unable to do anything, had no idea. Jayant it was who collected their ration of rice, dal, onion, oil, salt fish and chillies. He it was who queued up behind the impatient file of people waiting for the precarious fire to cook their meals every day. Every night she would pray that either Bhagwan returns her Raju to them, or take their lives, and as He did neither, she took it as a sign that He would give her daughter and her man back to her. Perhaps once they landed in Mareeshus, there they would be, beaming and smiling happily. Yes, definitely… perhaps… maybe…

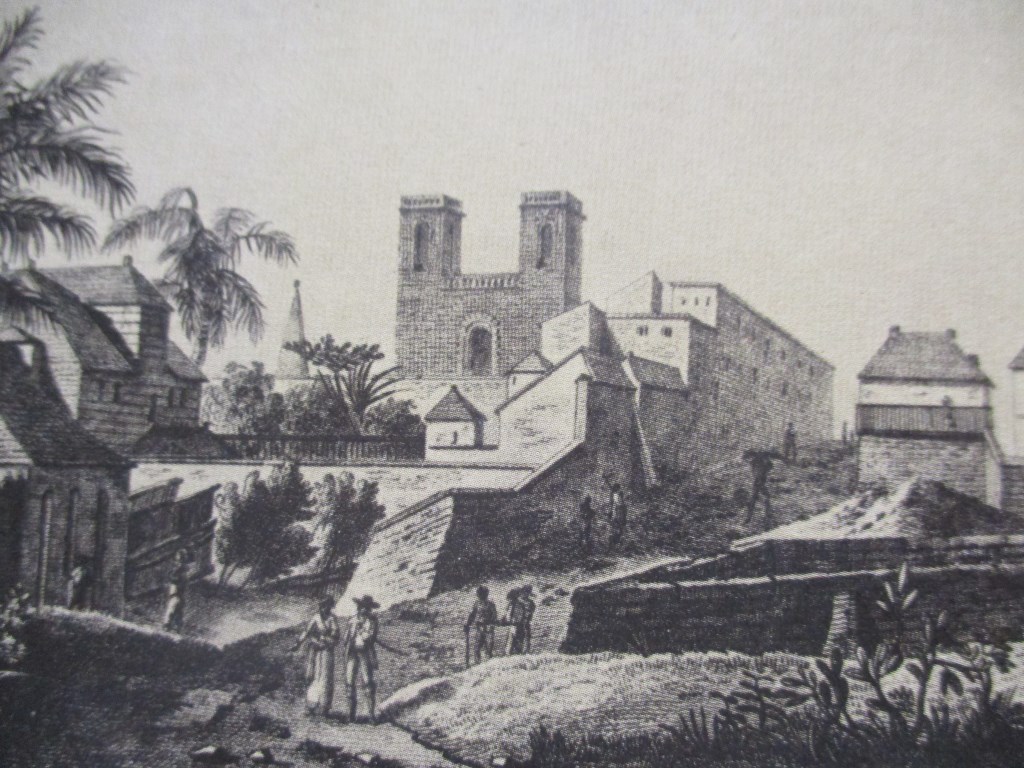

Photo Credit:

Unknown (Public domain, copyright expired)

Photo Credit:

Unknown (Public domain, copyright expired)

After the interminable voyage, one morning, Mauritius was sighted. But as there were cases of cholera on board, the ship was directed to Flat Island, and after three days when the sick were first removed, and the ship disinfected, it was allowed to sail into Port-Louis harbour. It was with apprehension that Shanti walked down the steps into the barge that was going to take them on land. She carried Pradeep and, Jayant the few possessions that they had. She had no inclination to look at the new world they were coming to. Without Raju, what did it matter. But Pradeep was wide-eyed with admiration. Look, Mama, the sky is so blue, the sea so calm. Look at the mountain uncle, he shouted excitedly as he pointed to Signal Mountain, doesn’t it look like a big cow resting. The Cokhan boatman smiled at him with his betel-stained teeth and patted him on the head. That man is so nice, Mama, not like the others. He meant the crew of the Startled Fawn who were always scowling and shouting.

As they were going up the steps at the Aapravasi Ghat, Shanti suddenly saw visions of the steps she took round the fire when she married Raju, with the heart-breaking difference that this time there was no Raju. Deep down she must have known that coming to this distant land was another landmark in her checkered life. Tears dripped down her cheeks, and Pradeep asked her what the matter was. Is Baba waiting for us, the boy asked. That was one thing Shanti had kept telling him, and it provoked more tears when the boy did not see his Baba. She had told Jayant that the first thing he had to do was to report Raju’s disappearance. Perhaps those clever Angrezi people who write everything in their big books already knew where he was. Jayant would have liked nothing better than to carry out her orders, but he was a shy and unassuming young man. With strangers he usually stammered, and he was dreading the encounter with an official. He spoke to a peon and this young black man shook his head. He did not understand, but he went to fetch a Bhojpuri-speaking peon, but there were five hundred people to be dealt with, and the clerks were very busy. Shanti saw red. If there are clerks, she heard herself say, not quite knowing what a clerk was, then you had better get one for me now, as I have one big big problem, my husband has disappeared.

‘Yes, captanine,’ he said and disappeared. Shanti did not smile, but that was the first time anybody had called her captanine since she had left home to marry Raju, and she would remember that all her life. After a long wait, a white man and his interpreter came along and without waiting for Shanti’s explanation, told her dozens of people had died and had been thrown overboard, and there was nothing he could do about it. She began to shout and scream, and before long Monsieur Hugon, the Protector of Immigrants himself, heard about her, invited her into his office, and listened to her attentively. When she had finished, he spoke calmly, and said that it was clear that her husband had missed the boat. She should not worry, because he would definitely be on the next boat which would arrive in three weeks. Shanti was much heartened by this, and calmed down.

Hugon gave orders that her registration be expedited, took down her particulars, and promised that the moment Raju arrived, he would send someone to Mont Calme where he knew she was going, to inform her. She, Jayant and Pradeep then passed their medical examination. Nothing very wrong with any of you, the medical officer said, that a little rest and two meals a day cannot put right. They received their tickets and passes and went to a smaller hall where the sugar cane planters or their staff had come to receive their new contingent of workers. Jayant would have happily accepted full responsibility for Shanti and Pradeep, at least until Raju turned up.

‘So you think Raju will turn up?’ Shanti asked him.

‘Arrey, bhabi, the Angrezi man said so.’

When Shanti heard that she was expected to replace her husband in the fields, she said that was fine, she had a good pair of hands, and would not need Jayant’s charity. Yes, Jayant had said, but you were born a lady, and grew up with naukars. Yes, one day we have servants, Shanti said, the next we become servants ourselves. In a matter of days, they were taken by oxcart to Mont Calme to join the work force of Monsieur Victor de Fleury, one of the most important sugar-cane magnates of the island. He had built a large number of very basic units to house his work force, and to Jayant’s delight and Shanti’s dismay, the foreman said that as there was a shortage of housing, and as Jayant was single, he would have to board with Shanti. He promptly reassured her that he would be happy to sleep outside under the jackfruit tree, or under the open verandah, if it rained. In fact, he would have been happy to sleep out in the rain for her. She had become aware of his unhealthy obsession with with her, and reacted by becoming increasingly offhanded with him. He seemed not to notice.