Chapter 5

(Tolpuddle, Dorset, England, 1834)

James Hammett had planned to do some serious poaching with Jonas that day, and his friend had promised some of his illicit brew. So, when John mentioned the two men sent by the London Union to show them how to organise The Friendly Society of Agricultural Workers, the younger brother demurred. John had a tendency to preach and although he claimed that it was up to the younger man to decide, he made it clear that he was disappointed, reminding him of the injustice and contempt with which they and their fellow labourers were treated by the bosses. He loved making speeches, did dear John and never missed an opportunity, even to an audience of one. He had the facts at the ready: It was a miserable life for all but the land-owning class. Children were bow-legged, small, with poor constitution because of malnutrition. They were prey to disease, because their bodies lacked so many nutrients, and obviously their kind had a very short life expectancy. Everybody dreaded winter as they could not afford to heat up their leaky and draught-ridden hovels. Wasn’t James aware of the practice whereby seven neighbouring families arranged for one of them to light a fire once a week, when the other families would bring their kettles to boil so they could have some tea to keep themselves warm, before hurrying to their icy mattress-less beds? Many people, the Lord grant them wisdom to know better, thought that death was preferable to that sort of existence. When John started preaching he was most loth to stop.

The average rent for something which bore only passing resemblance to a shack, was one shilling and tuppence, bread for an average family, 9 shillings, tea 2 pence, potatoes one shilling, sugar three and a half pence, soap three pence, candle three pence, coal and wood nine pence, butter four and a half pence, salt half a penny, and that did not include meat or fish which they rarely had anyway. That made for a sum which was in excess of what either brother took home in one week, in fact about one and a half times. Of course their combined earnings gave them an advantage at the moment, but surely James wished to have his own family someday, and with the new baby on the way, how would they manage? No wonder many supplemented their meagre incomes by poaching or illicit brewing. John abhorred the devil drink, but turned a blind eye to his younger brother’s occasional indulgence. With the Lord’s help James sincerely hoped that he might give it up entirely too, but not yet.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Marian Flynn Power

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Marian Flynn Power

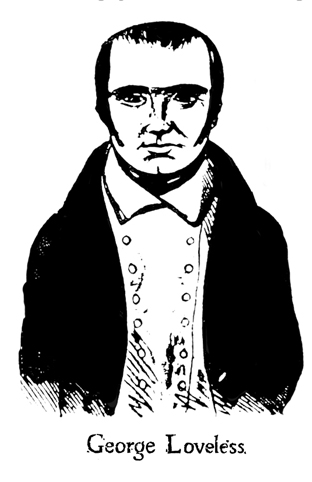

Young James was not insensible to the realities of life as an agricultural worker. He did not need John to tell him that the labourers were getting a raw deal from the bosses and that something had to be done. He was one hundred percent behind the schemes of George Loveless, but not today! He really meant it when he said that he was going to join the society, but he wanted a few hours of fun now and then. John had his own family to occupy his thoughts, a loving wife, two cheeky little boys and who knows who was playing peek-a-boo behind sister-in-law Madge’s round tummy?

Later he would remember the drink and the larking about with Jonas, but not if they had bagged anything that day. Still he remembered the proceedings of the meeting under the giant sycamore tree as if he had been there and stone cold sober too, such was the exaltation and intensity of John’s narration. James had nothing but love and admiration for the older brother, he was sure no finer man existed. He was a devoted husband, father and brother and although he abhorred the conditions of employment, never did the idea occur to him that he could give less of himself than one hundred percent. He was generous to a fault, but what the younger brother admired above all else, was that staunch follower of the teachings of George Loveless though he was, his generosity was rooted in his natural goodness and not his piety. He made James laugh when he produced a book the man from London had offered the Society and which George had urged him to borrow: “The Life and most Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner.” He had said that if they had a spare candle, he would have started reading it that very night so he could tell the little ones a new story. He stared at his young brother earnestly as he explained, clearly quoting the men from London who had come with a gift of books for the Society, in a clear move to encourage reading. A book is like rain water which the good Lord provides. One used it, drank it, and when it evaporated, it became clouds which became rain and fell on earth again and again. James was not quite sure what he meant, and his brother recognised this by his perplexed look, so he elaborated.

‘I read the book, and tell the story to the wee ’uns eh, James, then I do not need to read it again to tell it to the one to be born, and they will in turn tell it to their own little ’uns… you see… like the rain!’ His eyes glowed as he said this. If dear John had one failing, it was an undeveloped sense of fun.

The Society was running smoothly, but the bosses did not look upon it with favour. George Loveless had told everybody to watch their step, to always act within the law. James readily agreed to accompany his brother to the fateful meeting in the church hall a few weeks later. George who was a quiet and unflappable man, had seemed quite upbeat that time. Things are beginning to move, he told everybody. The Reverend Thomas Warren who did not have too much time for Loveless, himself a lay Methodist preacher, had surprisingly agreed to chair a meeting with agricultural workers and the landowners. It was going to be in the spirit of co-operation and fairness. A new era was in sight and nothing but good can come out of that.

Indeed, James was surprised at the peaceful nature of the assembly when he got there. Everybody smiled and talked politely to each other. The Reverend began by inviting George to have his say, and, in a dispassionate manner, quoting prices and earnings, he made a strong case for a need to review past practices. The reverend nodded sympathetically at everything he heard. The representative of the farmers, Sir Tobias then took the floor. Although Malfysing spoke calmly and in measured tones, James could not help guessing that he was inwardly seething with rage at having to share a platform with his obvious inferiors. He understood what Loveless was saying, he said, but let people not think that they were the only ones who were having trouble making ends meet. It would be a good thing if the workers learnt some discipline. They could not expect that every time they overspent they could claim a rise, this was unrealistic. James saw that Reverend Warren was nodding at these sentiments too. We are all in this together, the landowners were under severe strain too, he pursued. He was not saying no to their requests, but the people he represented needed to discuss the matter properly before arriving at a conclusion. George stressed that he had not come in a spirit of confrontation, but pointed out with a little laugh, that he could not believe that people who had stables where the horses were fed better than the workers for the sole purpose of chasing hares and foxes could claim to be under any sort of strain. Sir Tobias’ face changed colour, he scowled but said nothing. George then expressed concern at rumours to the effect that the landowners were thinking of decreasing their average wage by a whole shilling a week. Malfysing tut tutted and said that it was wrong to listen to rumours, whereupon George, who had been the picture of calm and self-control until now challenged the baronet to deny that this had been discussed only a week ago, not revealing that he knew the place, the time and exact words used on the occasion. For the first time Malfysing lost his cool and retorted that he had come to the meeting in a spirit of conciliation and not confrontation, and would not tolerate being cross-examined.

‘All I am asking for my men,’ said George helplessly, ‘is that we be paid the same as folks in neighbouring districts. We are the lowest paid workers in Dorset.’ He paused for breath and James could clearly see that he was measuring his words for a final salvo.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND ALISTAIR

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND ALISTAIR

‘Gentlemen,’ he said finally, ‘it is with regret that I say this: the law now gives us the power to withhold our labour-’ He was not allowed to continue. Malfysing and the other landowners stood up brandishing clenched fists and making indignant noises. Reverend Warren had to call everybody to order. He enjoined George to use more temperate language. The lay preacher managed to put across a final but crucial point, concerning the disparity between the wages of people of Tolpuddle and their neighbouring districts. There was no earthly reason why parity could not be established, seeing that they all did the same type of work, producing comparable yields.

The reverend was seen conversing with Malfysing, after which he stood up, beamed a no-grudge-borne sort of smile to George and solemnly declared that speaking in the name of the other employers, he saw no impediment to their wages being aligned with those of the folks in surrounding districts in the very near future. Now, the men from London had instructed George never to accept anything from the bosses except if it was on paper and signed, so respectfully he asked that an agreement be drafted there and then, and signed by all the parties. To his dismay, the bosses smiled to everybody and said that there was no need for papers between friends, for he considered every man in the hall as a true son of Dorset, and as such his friend. George was not sure, but the reverend came towards him, grabbed him by the shoulders and James heard him clearly utter those words that the man of the cloth would later deny: “I am witness between you men and your masters, that if you will go quietly to your work, you shall receive for your labour as much as any men in the district. If your masters should attempt to run from their word, I will undertake to see you righted, so help me God!”

What happened next stunned the whole of Tolpuddle’s workforce. They had been living in hope of a prompt implementation of the agreement reached in the village church hall, but Malfysing told whoever would listen to him that no agreement had been reached. He swore that he had only given “that rabble” as he called the workers, the assurance that at some point in the future, when things got better for the struggling land-owning class, he would discuss a review of the wage system for the workers. In the meantime, he regretted to say, that as a temporary measure, in view of the rising cost of seeds and feeds, the average wage of the workers would decrease by no more than one shilling a week. No one regretted this measure more than he.

Photo Credit:

Public Domain, historical illustration

Photo Credit:

Public Domain, historical illustration

George appealed to Reverend Warren and reminded him of the word of honour given to them by Malfysing at the church hall. What word of honour? the man of the cloth asked. He swore that no undertaking had been given, and confirmed the lie Malfysing had been propagating, namely that all that was agreed was that a review will be considered at a later date, when “things got better”.

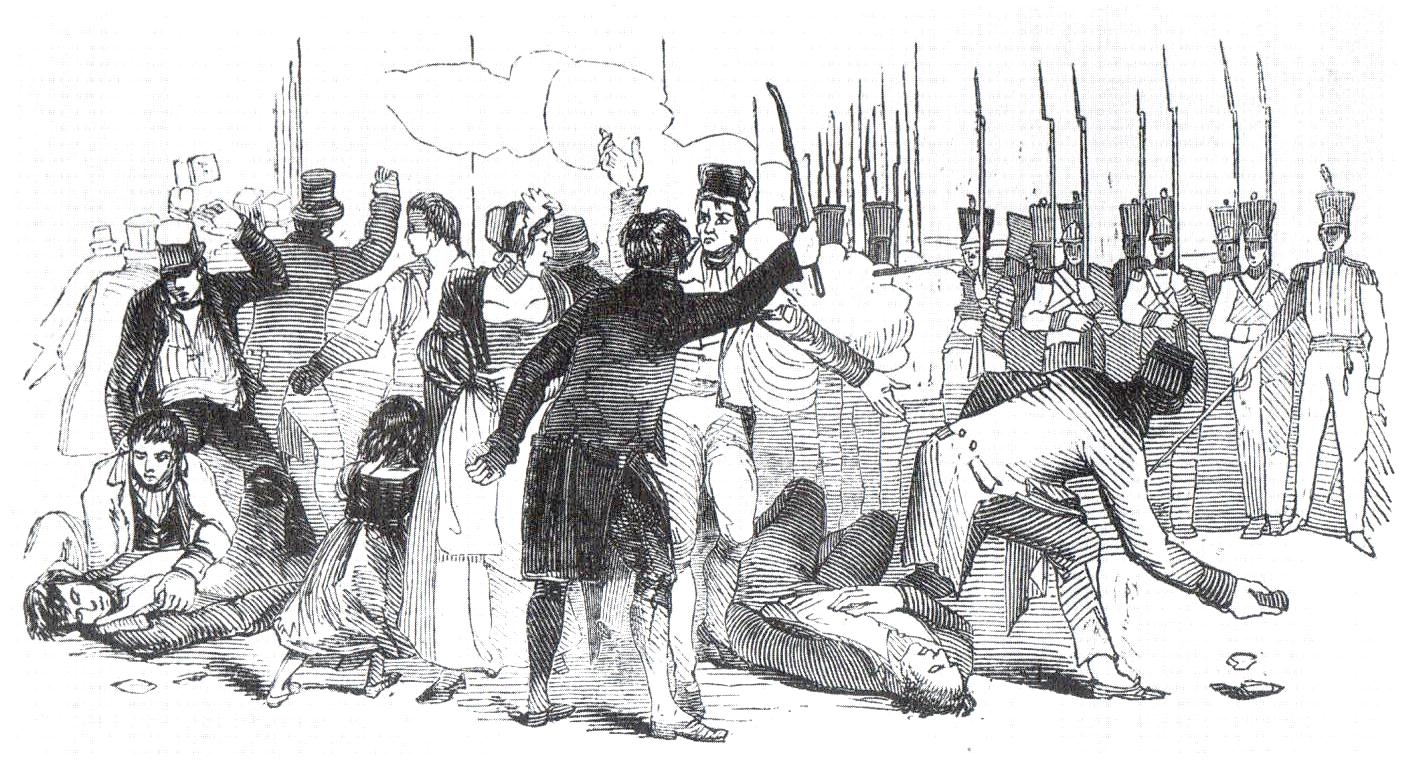

The anger of the victims could no longer be contained, but worse was to come. In the knowledge of their power and what was obviously a show of their contempt for the workers, the bosses decided to lower the wages by three whole shillings, bringing the average wage down to seven shillings. George agreed that the only thing left was to go on strike. Though still not a member of the Union, James was vociferous in his support for his peers and condemnation of the land-owners. Although others were clearly acting in breach of the law, damaging threshing machines and burning small fields of wheat and a barn or two, resisting his own inclination, he refrained from acting in any way which he thought brother John would disapprove of.

One morning a breathless George Loveless turned up at their dwelling and informed the Hammett brothers that the ring leaders of the Union were on the point of being rounded up. Clearly there was no point in running away when one had a family, he said. In any case, he said, apart from one or two lawless acts, the strikers now had the law on their side. At worse it would mean a week or two behind bars. John who did not have too much trust in the new law went pale on hearing the news. What will happen to Madge, he said, with the new baby coming, how is she going to manage? The three men were staring at each other helplessly when they beheld six law officers bearing muskets coming towards their shack. They let the uniformed men in and waited for the worse.

‘I have a warrant for the arrest of six individuals,’ the lieutenant said addressing George Loveless.

Photo Credit:

Believe this is Public Domain, historical illustration

Photo Credit:

Believe this is Public Domain, historical illustration

‘I am George Loveless,’ George said.

‘Yes, I have a G. Loveless on my list… you are under arrest, Loveless.’ George meekly tended his two hands together to be handcuffed by one of the men.

‘You must be J. Hammett,’ the lieutenant said to John, but before he could answer, James took a step towards the men, tending his two hands.

‘I am J. Hammett,’ he said, winking at John. Madge who was next to John retained him by pulling him by the sleeve, in case he did anything stupid.

‘And who might you be, my man?’ asked the lieutenant of John.

‘I am… his brother,’ he replied in a state of confusion which James instantly recognised.

‘I’ve only got one Hammett on my list,’ the officer said.

James knew his brother to be a man of honour to whom justice was the most important consideration in the world, and he read the torment inside him as an open book as he debated within himself the pros and cons of the situation. Was it fair to let his younger brother, who did not even belong to the Society, take the rap? On the other hand, who would take care of Madge and the babies if he was not there for them? James was single and had selflessly offered himself. The look on Madge’s face did not escape James either. It was a mixture of gratitude as well as an unneeded apology for the resentment she had often manifested when at the death of the elder Mr Hammett, she had to share the meagre resources of the family with him, thus diminishing the portions of her own little ones. Even at an early age, James had never borne her any grudge, understanding what mothers did and felt. He saw his brother take one step forward and his round-bellied wife retaining him yet again, whereupon he said loudly and with mock negligence that prison did not scare him, seeing that he had already tasted it. This earned him a sharp poke in the ribs from the lieutenant’s musket, and although it hurt, he made light of it and smiled wryly.

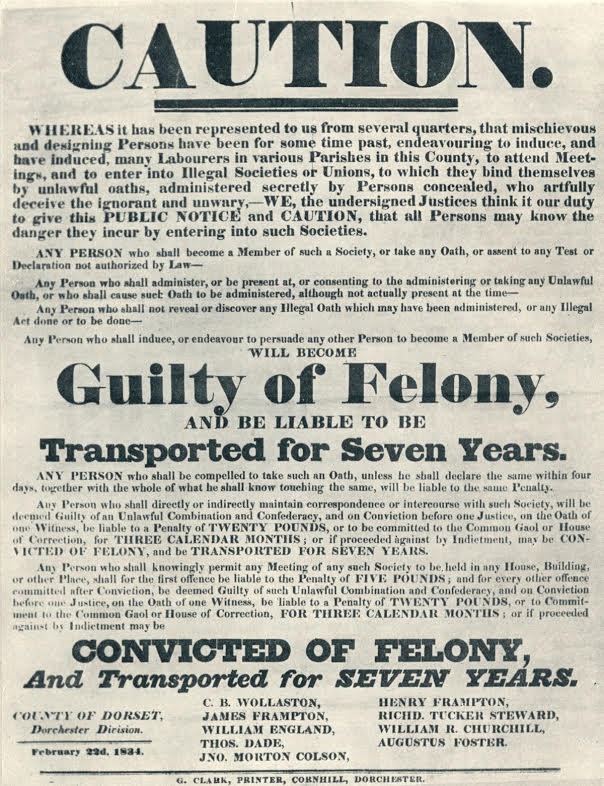

James felt strangely elated as he followed the soldiers to the dungeon where he was being taken with George. They would be joined by four others the next day. Mr Frampton the magistrate in charge of the case, had never been coy in expressing his conviction that the workers were the enemy within, waiting for their moment to turn this green and pleasant land into the anarchic mess that France had become since the events of 1789. He told everybody within his hearing that he had written to Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary to communicate his fears to him, and had obtained his blessing to deal with the scoundrels as he thought fit. Besides, his lordship had expressed to him the view that, the poor had only their lack of discipline to blame for their condition.

The judge appointed for the trial was Baron John Williams, and Frampton had impressed upon him the necessity to find the six accused guilty, pour l’exemple!

The hearing was to take place at the Spring Assizes in Dorchester on the 15th of March 1834. Mr Butt, the counsel for the defence began by pointing out that the Combination Act proscribing appurtenance to a trade union had been repealed, and this stumped the Baron Judge, but not for long. Ah, yes, he conceded, but what about the Mutiny Act 1820, which stipulates that people swearing secret oaths are guilty of treason? For which the penalty is death by hanging, he added darkly. The defence pointed out that the aforesaid Act was passed to stop sailors and soldiers swearing an oath to make a concerted move towards gaining better pay, or perhaps mutiny, and was clearly not aimed at agricultural workers or journeymen, but this left judge and jury, comprised solely of landowners, unimpressed. Several witnesses were called by the prosecution and James could hardly believe that people who openly professed their attachment to the teachings of Our Lord Jesus Christ could so unashamedly commit perjury and tell such barefaced lies, no doubt for rewards promised by the farmers. The defence called character witnesses who all testified to the good character of George Loveless and his followers in fulsome terms, but as Dissenters, they were seen by the jury as representatives of the fiend on earth. It was clear to James from the beginning that all this was a charade. Indeed the Foreman of the jury, the Hon. Ponsonby after a quick deliberation with his panel pronounced the guilty verdict.

The six men were stunned as they heard that they were to be transported to Botany Bay for seven years. If at first they had thought of a short jail sentence, it had become clear to them as the trial went on that they could expect anything, including the ultimate penalty. They were put in chains and taken to the hulk York in Portsmouth separately. George Loveless stayed there for a while and was then conveyed to the brig William Metcalfe, and on the 5th of May began a gruesome voyage to Van Diemen’s Island.

Photo Credit:

Believe this is Public Domain, historical illustration

Photo Credit:

Believe this is Public Domain, historical illustration