Chapter 1: The Ancestors

(Allapur, Bihar, Late 18th century)

Allapur, the most charming little gaon in the Gaya district of Bihar! Everybody agreed that the Allapur was the loveliest tributary of the Ganga, clear sweet pure water from the Himalayas, home to the best fish, prawn and crayfish in the country. Even the magnificent mahseer, the biggest fresh-water fish known to man, could sometimes be caught in its crystalline stillness as the swelling of the monsoon began to recede. The regular floods of Mother Ganga and the monsoon rains which were as dependable as sunrise, vied with each other, to soak and bathe this luxuriant paradise with their sacred waters, turning it into the most fertile land on earth, enabling it to breed the healthiest gai and goats, chickens and ducks, and produce the reddest tomatoes and the plumpest beans. Except when they politely told each other, after you Ma, no after you, Monsoonji, and then everything dried and shrivelled up.

Parsad’s ambition had been to become a teacher, but there were no schools when he was a boy. His Pitaji who knew book, had taught him what little he knew and had given the youngster his great love of learning which, unfortunately remained limited, but this did not stop him claiming that he valued learning above earning. Parsad never let slip any opportunity for picking up a new knowledge. The two books that Pitaji had given him, now protected from rains and insects by a pillowcase, volume 7 of The Upanishads and volume 3 of The Laws of Many, were in a sorry state, as he had read and re-read them a thousand times. He would ask questions of those who were able to provide answers, and considered it a pity if on any given day he had not learnt at least one new fact, or if a new thought had not crossed his mind. He was, however, quite content to carry on doing what his father and grandfathers had done before him, and settled down to the life of a peasant farmer. It was a noble calling and he worked on his fields with a fervour which, at the end of a hard day, found him in the same state of exaltation which religious devotees experienced after an intense puja session in the Mandir.

He had always thought that the land where he was born was paradise on earth, but lately the sky, like an angry woman who wanted to punish her husband for something she suspected that he had done, but would not spell out what it was, had decided to withhold its bounty. Every time you looked at the land, the small chinks zigzagging across the once smooth surface of the earth turning it into smaller and paler fragments, seemed darker and deeper than the day before as the drought and the scorching sun squeezed the life out of them. However, he always put his trust in Bhagwan who knows what He does. Not that he associated Bhagwan with the Mandir or the Pandit. He always felt uneasy in the company of the latter. Not that he did not believe in prayers and offerings, but he knew that he only prayed as a duty. It was the exaltation that made all the difference. He only truly felt elevated at the sight of little shoots pluckily forcing their way up having miraculously breached the crust of the earth, at the sound of the first bleat of a new-born goat, or the insouciant moo of his cow as she saw him approaching, at the warmth of a freshly laid egg. In those things he clearly saw Bhagwan’s bounty, and this Bhagwan, he worshipped with all the fibres in his body.

However, three successive years of parsimonious monsoon and drought had turned his land, once famous for its fertility, into a gnarled resentful patch which would respond to neither coaxing nor cajoling. You break your back carrying water from the river to the plants, but when you came back with a fresh bucket, the blazing sun had drunk it all. The seedlings had shrivelled up and died. Of the good-sized herd that he once possessed, the bulk had perished through lack of water and fodder. Still, he had been luckier than most people who had lost everything. Hundreds of villagers had slowly succumbed to the effects of starvation, especially the elderly, their existing ailments made worse by persistent hunger as the crops failed. However, Bhagwan in his wisdom, had saved his family and had even provided him with the means of saving the two remaining cows and one bullock if little else.

In the old days, he would whisper nice words to the growing tomatoes, lovingly caress their roundness and they would blush visibly and yield their delectable ripeness to him. Whilst in the old days, he would be all smiles, every pore of his body exuding gratitude for nature’s munificence when he stood in front of his fields, happy that this earth that he loved as much as he loved God, his wife and the yet-to-be-born sons, now he had only a mute curse, whenever he approached his bigha of land, “arrey sukkha chooth dayin!” - dried-cunt witch, taking care not to say these words aloud.

Although it had been his dearest wish to have a son, now that Parvatti had finally done it right, he was dreading his arrival. The timing was unfortunate. How would they feed him, clothe him, keep him warm when the temperature went down in the night, and when the cold winter rains came trickling in through the leaky roof? People he knew had moved to Jharkhand, where he had heard things were much better. There, one had not only the possibility of cultivating one’s own land, but as an insurance against unpredictable weather conditions, people said that there was the possibility of finding work on tea plantations, or becoming a carpenter, a trade he was familiar with, having taught himself by watching Vinod Chacha.

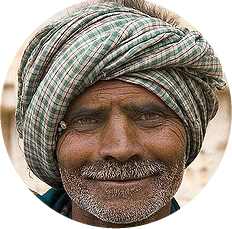

Photo Credit:

© Ananda Chakrabarti

Photo Credit:

© Ananda Chakrabarti

With the help of his friend and cousin Sukhdeo, he had built a boat which the two of them went fishing in, the fish caught, either providing for the two families or bartered or sold to the villagers. Now even the fish was gone as the water level had receded. First the clear water had turned into mud and finally the mud had caked up into dry rock hard bricks.

The two of them had been friends for ever. They had grown up together, had got married in the same year, shared everything, and had no secrets from each other. Parvatti was wrong when she said that Sukhdeo’s fields had a lower yield than theirs because he and Lalita were work-shy. She did not take into account that they had help from Parsad’s widowed sister Umma who lived with them. The way he looked at things, if he harvested more, it was his duty to share some of his crops with his friend. He would do the same for me, he told the sceptical Parvatti. He knew that Sukhdeo would die for him as easily as he would for him, if, Bhagwan forbids, the life of either was under threat. He knew that it was in a woman’s nature to doubt everything. Parvatti would smile sarcastically whenever he told her how devoted to him Sukhdeo was. Whenever there was any problem, like most men, he would discuss it with his friend rather than with his wife. She was a woman and wouldn’t have any idea. He trusted her in household matters. It was not a woman’s fault, but Bhagwan did not make women as clever as men.

The two friends met regularly under the peepul tree enjoying a bidhi on which each pulled with comical intensity, blowing the smoke out of their noses, nodding gravely at some half-formed idea before passing it on to the other, and sharing the last half of a bottle of toddy. The dry season had wreaked havoc on palm trees as well, and toddy was just as scarce as everything else. After two sleepless nights thinking about it, he had made up his mind to ask his friend what he thought of moving to Jharkhand.

‘Tell me, Sukhdeo, who are we?’

‘Why you ask? Have you forgotten?’ Sukhdeo was not known for his wit, but sometimes he could surprise his friend. The latter laughed and gave him his hand to clap.

‘No, I mean our race, our people, who are we? Where do we come from?’

‘Oh, I see. Do you mean Bihar… we are Bihari?’

‘Bihari! Good. Tell me, what does Bihari mean? In Sanskrit?’

‘Arrey, why you ask? Am I the one who knows book?’

‘In Sanskrit, Bihari means traveller. So, you see, we are natural born travellers.’ Sukhdeo still had no idea what he was driving at, but from Parsad’s grave tone, he suspected that he had something important to say.

‘So?’

‘With the conditions the fields are in, there is not much point staying in this dump. Sukkha chooth dayin! I think we should sell up and go.’

‘Go? Go where?

‘Have you observed the weeds growing on our land? What do they do when they encounter rocks?’ He did not give his friend time to respond. ‘When there are rocks in its path, the weed will produce longer stems and tendrils allowing it to circumvent the rock in its quest for soil, is all I am saying.’ Sukhdeo did not always understand his friend’s drift, but he was full of admiration for his way with words. Parsad then mentioned Jharkhand, and the good things he had heard about the place.

‘Oh, Lalita would never agree, all her relatives are here.’

‘Relatives, yes, of course,’ Parsad said as if he had never given any thought to them.

‘Why you ask?’ Sukhdeo suddenly said in alarm. ‘Are you thinking of going there?’ He stared at his friend for a while and then almost wailed. ‘No, you cannot go without me…’

‘Arrey yaar, I will never go anywhere without you, you know that.’

‘Lalita won’t budge, so best not to talk about it again.’

Sukhdeo is my friend, and I cannot do anything without him, he thought as he lay in bed listlessly, on his third consecutive sleepless night. Parvatti found it difficult to sleep when her man kept sighing and tossing about.

‘Arrey, you are not sleeping, you keep sighing and scratching, why don’t you go to sleep?’ It should be obvious to anybody that one does not choose insomnia for the fun of it, but now that she had this little boy growing inside her, he was even more tender and loving to her. He just smiled to himself in the dark. She was such a fine person and he loved her so much, even if she was not all that bright.

‘Piari,’ he said, ‘we are producing nothing here.’

‘Yes, father of our unborn child,’ she immediately agreed. ‘Have you thought of how we are going to feed this extra mouth?’ At the same time she caught his hand and placed it on her round belly. It was smooth and warm, and he could feel it pulsating as she breathed in and out.

‘I have thought we could move to a better place, but the relatives? How can we leave them?’

‘Arrey, relatives, belatives!’ she said dismissively. ‘Will they feed the baby when he will have no food?’

‘That’s what I told Sukhdeo,’ he lied. He sensed her anger and knew immediately that she resented the fact that he had first talked to his friend, but it was an age-old thing.

‘Maybe we should go to Calcutta,’ she said. ‘I have heard that the Angrezi have big plans and that people there are doing very well.’

‘Don’t talk to me about the Angrezi,’ he said bitterly. ‘After the battle of Buxar, where my Pitaji lost an arm, they claimed diwani rights, took people’s taxes and promised to govern fairly, but what did they do?’ He paused for breath, and with uncharacteristic indignation fired his last salvo. ‘They cannot even guarantee rain, pteh!’

‘You say there is no work here? You are a good carpenter…’

‘There is nothing. I have asked everybody. When no one earns anything, people don’t wants chairs and tables. They sit on the ground and beat their chests. There is only one thing left to do.’ He took a deep breath but said nothing. Parvatti turned her head towards him in expectation, but he seemed lost in thought.

‘Haa..n?’ she questioned. All he could think of was to say, ‘Tomorrow we go to the Mandir and pray. Buy some bananas and coconut.’

‘Arrey, you men are so clever,’ Parvatti said. ‘We have no money, and the only remedy you can think of is to spend what little we have buying bananas and coconuts for Gods.’

Photo Credit:

butforthesky.com

Photo Credit:

butforthesky.com

He did not approve of her flippancy, but said nothing; she had not finished. ‘If Bhagwan wants to help, does he really want us to waste what little savings we have on him? Arrey, he can get all the bananas and coconuts he wants up there in Svarga,’ she said. And he probably has no time for bananas and coconuts anyway, he must be gorging himself on good expensive cakes from London England that come in tins with pictures on them.’ This time she was going too far.

‘Be careful what you say, piari. Sometimes you are so lacking in respect,’ he tut tutted. ‘No, we go to Mandir tomorrow.’ She said nothing for a while. If he wants to go to the Mandir, it is a waste of time, but I am too sleepy to argue.

‘Jharkand,’ she said suddenly. ‘My cousin Bhobesh, he went there, and auntie says he is doing all right. A mosquito began to buzz in the far corner of the room. They kept quiet in expectation for its next move. The little buzzer buzzed for a bit and finally landed on her forehead. She slapped it and of course missed.

‘You should have spat on your hand first,’ he said. She had no idea what he was talking about, and turned to him to ensure that he had not lost his marbles.

‘My Pitaji… Oh Piari, what a saint that man! He used to say that if you have wet hands, it’s much easier to swot mosquitoes. You should have spat on your hand.’ Mysteriously the mosquito flew away, at least for a while.

‘But Sukhdeo doesn’t want to go to Jharkhand.’ Parsad said tearfully. Parvatti was unable to hide her anger this time. She pushed his hand away from her belly, sat up in one quick movement, was on the point of giving him a mouthful, but decided to express herself more moderately.

‘You mean, father of my unborn child, you mean you have discussed this with him first? Is he your wife or am I?’ He could not see why that was a problem, but he was not insensitive enough to voice his true reasons: women do not understand these things. It is well-known that they have smaller brains. The Pandit said so. Still, sometimes she surprised him and he had begun to wonder whether Parvatti might not be an exception to this age-old rule.

‘I have known him so much longer,’ he said weakly. ‘Anyway he says Lalita will not move from here.’

Parvatti shook her head and said that she did not understand his stance. If Sukhdeo wanted to stay in this dump, he was welcome to it, but to her, there was no choice. She would never let her baby starve because Lalita’s relatives lived in Allapur. Anyway doesn’t she hate them all? As far as Parvatti was concerned, they should leave for Jharkhand, and the sooner the better, because in a matter of days she would be in no position to travel. He said nothing, but he was not happy.

Women did not understand about the friendship between men, and seemed jealous of it. This bond was something as sacred as the love between a man and a woman, but on a different level. A man needed a woman for her beauty, her body, to cuddle and to make love to, to look after the family’s needs, to bear and rear children. There was no greater pleasure than to link your two bodies together and be one for a while, and sleep with your arms around each other, at least when it was not too hot. With a man, it was everything else, you can talk to a man, make jokes, tell stories, share a smoke and a drink, discuss serious matters. You can expect a man friend to lay down his life for you, and he can expect the same from you. You are of course ready to lay down your life for your woman, but may Bhagwan preserve good men from the shame of a woman giving her life for you.

Think of the boy, she said. Surely we want to give him a good start in life. Parvatti had a point there. She had insight, she was indeed sometimes as clever as a man. He must find a way to convince Sukhdeo.

Photo Credit:

© Ananda Chakrabarti

Photo Credit:

© Ananda Chakrabarti

Fortunately next day, it was Sukhdeo who surprisingly said that Lalita was of the opinion that there was no future in Allapur or Gaya, or even Patna, and that they should go to Calcutta. The battle was won. The details could be worked out later. Umma, with whom nobody discussed anything, had no choice but to accompany her brother and Parvatti to wherever they decided. Nobody asked her opinion, she was not expected to have any. Not only was she a woman, but she was also a widow, and as such, she had no rights. Brothers looked after their widowed sisters, as a sacred duty. However, in this case, Umma knew that it was with grace and generosity that her younger brother did this, because he was a good and loving man. She remembered how they used to tie a rakhi round each other’s wrists every year before she got married, swearing eternal protection to each other. He knew that if fate had wished it, roles might have been reversed. He could have been the victim of a serious accident and Umma would have looked after him with the same devotion. Of course she worked in the fields, did more than half the housework, washing and mending the family’s clothes, cooking and cleaning.

Parsad listened to his friend, and then explained that Jharkhand was nearer, and made it possible to come back and visit friends and relatives, not too often, maybe once or twice a year. Sukhdeo said that Lalita would like that, said that he would ask, and was surprised when she agreed. The friends stared at each other for a few seconds, unable to speak, as if under a spell, then suddenly they nodded to each other. Yes we will take the plunge. Go to Jharkhand in the first instance, and if that did not work out, then they could always go further.

Sukhdeo had next to nothing, and depended on his friend who still had his two cows and a bullock and a cart. He also had some money and besides, Parvatti had jewellery. It was a tradition when the going was good, for a husband to buy jewellery for wife and daughters, which they would wear at their leisure, but there was always an understanding that in an emergency, they could be used to bolster family finances, by pawning or selling. Lalita, for her part had none to speak of. They took no more than a week to prepare for the departure.

Parsad had enquired from people who claimed they knew about the road, and had even made a sort of map. At first he had no idea about the daunting distances involved, but by the time he realised the enormity of the project ahead, the momentum had become unstoppable. The two men had hoped that they might have made some good money by selling their land, but the only big zamindar who had expressed an interest, knowing they were desperate, offered very little and they had no choice.

They said their tearful good-byes to everybody and loaded their possessions on the cart, and the five of them left Allapur with an equal mixture of optimism and foreboding. It was very much a shot in the dark, but the wretched condition of Allapur made them see the unknown place they were aiming for, which nobody knew much about, as a land of plenty wrapped in all the colours of the rainbow and where the aroma of jasmine and gulab filled the air.

As there was only enough room for two people in the cart, in view of the possessions of the two families, they sat inside and walked in alternation. The resolute Parvatti tried to make a case against the preferential treatment everybody, Lalita included, insisted upon for her, and was voted down. Suddenly, without warning, it began to rain. It was not just a drizzle, but a downpour, and the travellers looked at each other wryly, none having second thoughts, and they did not look back.

After two days, they reached Bodh Gaya, and as none of them had seen this marvel, they spent a whole morning looking at it from all angles, together with hundreds of pilgrims. They sat under the Bodhi tree and meditated, praying for guidance and prosperity. Parvatti collected a few seeds, intending to plant them when they found a place to settle in.

‘Yes, good idea,’ said Sukhdeo. ‘Our new house will be blessed.’

‘All I am interested in, is a nice big tree like this one, to provide shade for us,’ said Parvatti. Sometimes Parsad despaired of his wife, loving and lovely though she was. First she was not all that bright, and now she is being disrespectful to the Supreme Being. Lalita ordered Sukhdeo to pick Bodhi seeds too, as she did not want to lose out, either on blessing, wealth or on shade.

After Bodh Gaya, they made for Sagarpur, and that was a never-ending, bone-shattering journey. The heat was relentless and the wind dusty and dry. The pregnant Parvatti, who should have been taking things easy felt the strain, but she did not complain half as much as Lalita. As long as I do not have a miscarriage, she thought. Please Bhagwan, she cried aloud one night, be merciful, do not let my unborn baby pay for my impious thoughts. Bhagwan is not vengeful, piari, Parsad said, taking her hands in his, He knows you do not mean those impolite things you say. She did not tell him, but she did. She often used to think that if just some of the thousands of gods paid the slightest attention to the millions of poor people who prayed to them so frequently and with such fervour, it would impossible to understand why there was still so much poverty and wretchedness on this earth. Live to be a hundred, she will never understand what her Pitaji had done to deserve Bhagwan’s ire and all the afflictions visited upon him in his lifetime.

Lakhaipur, Fatehpur, Danua followed, and the travellers were bearing up quite well. Except that Lalita never stopped moaning: When it was hot, it was too hot, she was being fried alive! When at night it freshened up, it was too cold she could feel her bones turning to ice; when the atmosphere was heavy and still, she sweated and complained, and when there was the slightest breeze, the wind was blowing dirt in her eyes! Parsad was so proud that the pregnant Parvatti never complained. They ate what they could find to buy, they fished and sometimes, they stole from vegetable patches at night, promising themselves that when they were in the money, they would pay back what they had stolen with interest to the Pandit for his Mandir, swore that they would never shoo away beggars, even if their blindness or crippled condition were fake. On some rare occasions they found work on fields and Parsad mended broken wheels or fixed tables and chairs for some villagers who gave them food in return. The cows gave them milk and they spent memorable nights, often sleeping in the open air, under the protection of stars, sometimes around a wood fire over which they roasted a wood pigeon or a small hare when they caught one. Parsad did not have to be begged to tell them stories of Birbal and the Mahabharatha that his father had told him. He had a special fondness for Birbal, and regaled them with the tales of Akbar’s confidant, clown and adviser, leaving everybody in good spirits, enabling them to sleep better and thus wake up refreshed in the morning. Everybody, Lalita included, fussed over Parvatti and there was never one cross word exchanged between them until now.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND sandeepchetan

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND sandeepchetan

It took them over a month before they reached Hazaribagh which proved true to its name of place of a thousand gardens. Parsad’s first reaction on seeing the hilly slopes with its breathtaking patches of colour, was to cry out to Parvatti, Look Piari, the moon collided with a rainbow in the night and the bits have fallen over the vales. Marigolds and poppies, wild hibiscus and a multitude of flowers unseen in Allapur, and the undulating hills which reminded him of lovers intertwined, were one rhythm locked in another. Do we need to go further? Parsad asked in a tone which left no one in any doubt as to where his own inclinations lay.

They had all fallen in love with the place, although Lalita, perhaps wisely for once, said, flowers are nice to look at and smell, but can one eat them? They found a nice sheltered corner in the forest and decided to stay there whilst they investigated the place. They were aware of the dangers lurking in the surroundings. They knew about tigers and pythons, wolves, jackals and wild boars, and hoped that a fire kept going all night long would be enough to deter those beasts. They found some alti kachu or cocoyam growing on the banks of a small stream. They caught a one-year old nilgai, killed it, skinned it and roasted it together with the yam over a wood fire, spreading an aroma which blended with the forest’s own distinct smell of dried and decaying leaves which they would later be able to recall effortlessly, and had an unforgettable feast. They arranged to sleep round the ghari, needing only thin sheets to cover themselves with, and for the first time since they had left Allapur, they felt relaxed and slept soundly, unperturbed by the buzzing of mosquitoes. They were all surprised at how quickly their muscles got used to their daily walking marathons.

The people had seemed nice enough, and had assured the newcomers that water was plentiful. They explained that the place not only benefited from a generous monsoon, but was blessed with waters of the Ganga Jamna and the Damodar as well as a multitude of their tributaries. The soil was dark and rich, and they made up their mind to start looking for land. They found a family who had a small plot to sell and started negotiations with them. It was smaller than what they had hoped for, but it would have to do for a start. With Bhagwan’s blessings they would use the profits to extend and buy more land. Parsad and Sukhdeo were convinced that they within a day of agreeing terms with the prospective seller.

On their second night their optimism had become uncontrollable, and they spent a whole night round a fire, in great spirits, watching the golden yellow flames dance merrily to the tune of the cracking music of the embers, making plans and telling stories. There was an abundance of trees, fruit trees, pines and banyans as well as other common denizens of the forest. At one point, as their fire was going out, the men went to find more wood, and in the semi-darkness they thought that it would be easiest to cut a few branches from an old jackfruit tree. They had not slept as soundly as this since before the onset of the drought.

In the morning however, they were woken up by a big racket, and to their consternation, they saw a small crowd of men, women and children brandishing sticks and making angry noises, surging towards them, nothing about their shouting and the expression on their faces indicating that they were well-disposed to the newcomers. Lalita said that the people might be thinking that they were chamars, untouchables, who were soiling their environment and were bent on driving them away. Tell them we are not chamars, she urged the men, tell them that we come from the best families in Bihar. Parsad felt stupid, but with Sukhdeo’s help, they tried to convey that information to the mob, but they realised that their bhojpuri was hardly understood. They had no nagpuri, which seemed to be the language of the mob. A young stalwart with a pleasant enough face, contrasting with the hostile scowls and pursed lips of the crowd, finally managed to explain in bhojpuri that they were to follow them, leaving them no choice. They meekly did what they were told, spurred on by the angry and menacing crowd. Some of the younger men began prodding them in the ribs with sticks, but they were ordered to stop by an elder.

They were led to where the two Bihari men had cut some wood from the jackfruit tree. It was then that Parsad noticed that all the trees in the area had a pink string tied round them. Everybody began talking and expostulating at the same time, and the young bhojpuri speaker explained that they had broken a sacred law of Jharkhand. They had damaged a protected tree. How could they not have seen the rakhi strings tied round them, they were asked. Parsad explained that it was not their intention to break their laws, that they were peaceful people, Bihari folks who did not know the local customs, and in any case, they had not seen the pink strings in the dark. Tell them to pack up their things and leave, shouted a small group, tell them they are not wanted here. Biharis are worse than Chhamars, shouted a small group in nagpuri. The young interpreter then explained about Rakhi. Rakhi? Meaning no offence, wasn’t the rakhi for brothers and sisters? Parsad asked. The young man smiled and shook his head, and translating the cacophonous flow of words from the crowd, explained that in Jharkhand, people considered trees as their own flesh and blood, effectively their brothers and sisters. If everybody chops down trees wantonly, in no time at all there would be none left, someone said and the young man translated. So the folks tie a rakhi round chosen trees and expect everybody to respect them. Even picking a single leaf from a protected tree was an inexcusable offence against sacred Rakhi lores.

They apologised profusely, pleading ignorance and promised that never again would they show disrespect to the local people and their customs. The young stalwart translated and the group dispersed, although no one except one or two men smiled and nodded to the pregnant Parvatti as they left. No great harm done, sighed Parsad, we ve salvaged our honour, but he was wrong. It seemed that the whole of Jharkhand had heard about their misdemeanours. People who had previously received them graciously now turned their backs on them. The farmer withdrew his offer to sell them land, and they knew that no one else would.

They had said from the start that if Hazaribagh proved unsuitable, they would make for Lohardaga, but they all asked themselves one question: Why would Lohardaga be any better than Harazibagh? Only Lalita voiced her reservations. She started screaming that she wanted to go back to Allapur, that she was always against that stupid idea, and for the first time ever, Parsad heard his friend tell his wife to shut up.

‘Do you want to go back to that place where we have nothing, and starve? Go by yourself if you must!’ He regretted his outburst and tried to bring a conciliatory note in proceedings by saying that he had heard that the Subarnarekha river had made Lohardaga prosperous, that there was rich soil all along the banks of its many tributaries. You just take a look at the dark soil, he said.

The optimism at the start of their trek was now in tatters, revealing the extent of the nakedness of their prospects, but they had no choice. In Lohardaga, which they reached after an exhausting trek, they were advised that they might be able to buy some land at a good price in a small village called Hundru, and ended up there.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND sandeepchetan

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND sandeepchetan

They thought that it was a promising place, and believed that they could be happy here. A zamindar on the Subarnarska river had some land he wanted to sell, and they went and had a look at it. Even the naturally fault-finding women were bowled over. The zamindar was marrying his first born, which was why he needed the money. Parvatti, forgetting that one does not address a male stranger, suddenly asked if Zamindarji was not planning to give the newly weds some almaris and tables. The man was so stunned that he forgot to frown, and there and then an agreement was reached, whereby the land changed hands for a mixture of money and furniture.

Hundru seemed like a really good place to start a little their new life. The friends ended up with about two bigha of prime land each. They began by building a small hut for each family and dug an irrigation canal which would bring water from a tributary of the Subarnarska to their fields. They were very optimistic about making a real go of this new situation. As luck would have it, another rich landowner was also marrying his daughter, and Parsad was again asked to make an almari, a bed and two chairs for the couple. This was an unexpected bonus which helped him buy a couple of goats and some hens for himself, and the same for Sukhdeo. (“He would have done the same for me, piari”.) They sowed vegetables, beans and pulses, built pens for goats and in anticipation of better times, a stable for yet to be purchased cattle. The hens roosted on trees.

The crops were excellent, the cows gave good milk, the hens laid eggs a-plenty and they made good profit. However, gradually they discovered that the people of this new place were no better than those of Hazaribagh. They were now openly hearing people saying things like “Ek Bihari Sau Bimari” (one Bihari hundred diseases). The news of their success was making folks in the area jealous, and they found that the goodwill which they thought they had earned by their hard work, was but an illusion. Still things were looking up for the pioneers, and to crown it all, Parvatti was delivered of a fine little boy. They all saw this as a happy omen, good things on the horizon. The boy was called Rajendra Parsad, and known as Raju. The birth was difficult, and Parvatti, already exhausted by the long trek became very weak after the delivery.

It was the baby, more than anything which made the place tolerable to them, but the land also continued to produce good yields. My boy has brought good fortune to us all, Parsad told everybody. However, less than a month after Raju’s birth, Parvatti caught a chill in the rain one morning. Parsad was distraught, and prayed day and night for her recovery. The neighbours surprisingly rallied and recommended a Sadhu, who they said had a gift for healing second to none, but even he had to admit defeat. You wasted valuable time, he chided the distraught husband. You were crass and stupid! You should have sent for me straight away, now by your fault, the devil’s work has gone too far, there is nothing even I can do now. Pray to Bhagwan to forgive you your stupidity. He spat on the ground, muttering, Stupid Bihari, what else can you expect from them!

That night, Parvatti was in a sweat, feeling hot and cold at the same time. Parsad was disconsolate and knew not what to do. He sat by her side, took her hand in his, every now and then wiping her brow with a cold compress. He could see that she badly wanted to say something. He tried to discourage her, but she smiled wanly and insisted on talking. ‘Tell me, how… what you did when your Pitaji told you that he was getting you married to his friend’s daughter… to me?’ She smiled wanly and he did not fail to detect an impish glint in her near lifeless eyes. He felt uneasy, turned his head away, and with a guilty smile he admitted that he had run away because he had not wanted to marry someone he had never seen. She shook her head, the glint in he eye slightly more pronounced. You thought I had buck teeth, she managed to say with a large smile. ‘Yes, some liar had said… but the moment I cast my eyes on you, piari, I knew I wanted to share my life you,’ he said, making an effort to keep his voice from breaking. ‘I know,’ whispered Parvatti letting go of his hand, but the smile was still there. ‘Even if you had buck teeth, I would have wanted no one else,’ he muttered, but she never heard him. Parsad never cried in public, not even in front of Sukhdeo, but the death of his beloved wife shook him to the very foundation. Although he had qualms about widows feeling obliged to commit suttee by throwing themselves on their husband’s funeral pyre, he felt that he would not have needed much encouragement to do the same, as Parvatti’s human remains rose up in smoke on their way to Svarga. Bhagwan would surely accept her in that blessed place. He was not vindictive. He surely knew that she liked to laugh and say things she did not mean, but she was a good woman, the best.

It did not take him more than one week of marriage before he became convinced that he could not have had a better life companion. He had wrongly thought that like all women, she was not terribly bright, but as he sat under the guava tree on his own at sunset on the day of the immolation, he could remember any number of occasions when she had dazzled him by her common sense. Her fortitude during that exhausting trek was an example to everybody, and no doubt it was the fatigue which had sapped her strength and finished her off. What had possessed him to contemplate this reckless adventure? Nobody could understand the magnitude of his sadness, the gnawing regret, the guilt, the depth of his loss. He had lost not only a wife that he loved to distraction, but his best friend. He wondered if she knew the strength of his devotion to her. Did she understand that when he had seemed to be putting her down, he had only been joking? He knew that he had not known how to express his unbounded love for her properly; he was a clumsy man. She was such a forthright woman, had such generosity. Never once had she made poor Umma feel unwanted. How many wives would have been so willing to share the little they had with a third person? Only now he realised fully what a sound head she had on her shoulders. He had been such a brute. If it was possible to put the clock back, he would do things so very differently, he would cherish her as she deserved, and make sure that she knew what his real feelings were. He knew now what an admirable woman she was. How could Bhagwan be so heartless?

From that day, although he would continue to recite prayers, no one would ever hear him praise the Lord. As his copious tears streamed down his cheeks, he could feel the sorrow deep inside his belly as a real physical pain. Were it not for the little boy, he would have prayed for death so his aatma could go and join hers.

Umma was a devoted mother substitute to Raju. They tried to rebuild their lives, but Parsad became disenchanted with Hundru. To his surprise, his greatest ally in this was Lalita. She had never stopped hankering after Calcutta, and now he found himself listening sympathetically to her constant evocations of that paradise on earth. In the past he had always dismissed whatever she said as the rantings of a mad woman. Besides he regularly heard people talking about the capital of British India, and how easy it was to make a good living there, how everybody was so much better off than the poor peasants of Hundru or Lohardaga, and so on. Calcutta was very much in everybody’s mind. Raju was two years old by now, and had turned into a healthy and spirited little boy, cherished by everybody, with the possible exception of Lalita, who would have dearly loved to have a son of her own, and as a result resented the toddler. Parvatti, who mistrusted her husband’s friend, would have been surprised at how fond of the boy Sukhdeo was.

One fine day, the two men did it again. They took the decision to move to Calcutta. Lalita now declared that she was against the move, but the men were adamant. You are lacking in ambition, Sukhdeo said to his wife. You women can only see where the next meal is coming from. Men have to think of the future, and the future was Calcutta, where the British East India Company were working miracles for the benefit of the people of this land. Parsad was still dubious about those Angrezis, but said nothing.

Umma yet again had no say in the matter, but she had found a new role in her life, that of mother substitute to the toddler. Nothing else mattered. Parsad readily agreed with everybody who said that no mother could have done better for his little boy. Her devotion to both of them was total.This time the farewells were less tearful, and the trek was much more strenuous, but their determination was just as strong.