Chapter 6

(Sundarbans, Eastern India, 1820s)

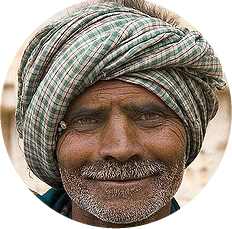

Raju’s memories of his pre-Sundarban days, was a mixture of half-remembered facts and stories told by elders which had become more real every time he heard them. Did he really remember the interminable walk across deserts and swamps? Or being found under a rock one sunset crying his eyes out, by uncle Sukhdeo, after being lost for a whole day? Phoopi Umma never tired of telling him stories of his childhood. As he never knew his mother, all his life he would endow her with all the qualities of the best women he knew. Phoopi was the best model of course. Widowhood had turned her hair prematurely grey and Raju thought that she looked very dignified like this, frail and thin though she was. Because of a back problem resulting from long hours of bending down over her nets in her quest for Bagda Chingris, knee deep in muddy waters, she walked with a stoop. A proud woman, she disliked this much more than the pains in her body since these she could keep hidden from the world. An all too visible stoop was a weakness which was there for all to see. She always spoke in deliberate and measured tones, taking trouble to articulate every syllable clearly. Some people said that when one was a pauper dependent on a brother, putting on airs was like farting through one’s navel. It hurt Raju that a woman who never uttered one malicious remark about others, could attract such obloquy. When the boy commiserated with her, she would smile wanly, and say that she was like kochu leaves. When you poured water on that cocoyam plant, the drops danced merrily on them like live silver jewels and leapt away. Try as much as you want, you cannot wet a kochu leaf. When one is a poor widow, one learns how not to hear bad words. He would later understand that people said hurtful things because poverty and hunger made them mean-spirited in their speech, but it was rare that anybody would do bad things to you. In reality, when you were in any sort of distress, the whole village would forget past rancours and jealousies and rally round to offer succour, however modest.

Even after Baba Parsad had married Ma, Phoopi, a few years older, remained the head of the household, deciding on what to eat and what to wear. He never knew his Ma Parvatti, but he saw her regularly in his dreams and knew exactly what she was like. Of course she was the prettiest, kindest and wisest of all humans. In appearance she could have been Phoopi’s twin sister, but not as dark-skinned, with infinitely gentle eyes, wrapped in a glow of white light wherever she went. Raju imagined that Phoopi and Ma had been the best of friends, that their relationship was one of sweetness and light, laughter and love, the older woman giving advice and encouragement to the younger one, who in turn would massage her neck and tired legs when necessary. It was true that Phoopi and his Ma were always the best of friends.

According to the aunt when the migrants finally arrived in Calcutta, a few years after leaving Allapur, people in this new place had looked upon them as Bhojpuri-speaking beings from another world, therefore uncouth intruders who talked funny, ailé gailé, kaa ba, kon chi ba? and had awful habits. Bengalis have class, they are poets, musicians, their middle name is Probity. Biharis are bandits, vagabonds who were unable to stay in one place.

What little money they had possessed, was now all gone. Work was harder to find than fish up a tree. They had been discouraged to stay where they wanted, and had been forced to leave for the least salubrious part of the city, the outskirts, where, if they found work, it was laborious and badly paid. Parsad and Sukhdeo had ended up miles from the centre in Roshankhali, one of the islands of the Sundarbans. It was situated near Sonarkhali where the mangrove forests can be said to begin, where because of the salt contents of the earth almost nothing grew but weeds and shrubs. Besides all sorts of dangers lurked in every corner, coming in all shapes and sizes: mosquitoes, man-eating tigers, crocodiles which left their shores and roamed the land in search of prey, sharks, cobras, rats as big as cats. On top of everything, in the rainy months the monsoon reigned supreme. The women in the village used to say that the monsoon was like husbands. A woman needed one if she did not want to starve, but then you have to put up with his exigencies. Without water, the land dies, but with the monsoon, it rained all the time, you walked knee-deep in mud. The cyclones joined in to cause more havoc. They were able to lift people or cattle up in the air and hurl them to their deaths against trees or rocks cracking their skulls, or into the boiling sea where they drowned. They wrecked boats and caused more drowning. Any little extra grain that people kept as an insurance against the lean months were often irreparably damaged when the rains came in through the leaky roofs, or unimpeded if the roof had been blown away. When the floods came, they drove away everything in their path, they uprooted trees and carried away people and habitations, leaving bleakness and misery around.

The Allapuris were left with no choice but to endure all this, and after two years, they settled in this new life and were not doing too badly for themselves, although they did not always have two square meals a day. Of course when the weather was good, it was the most glorious place on earth. It was like a husband in the first month of marriage. The place would be ringing with the singing of birds, luxuriating in a green splendour that was unparalleled in the country, with a wealth of vegetation and flowers of every colour under the sun. A stranger could not easily imagine that this paradise could metamorphose into hell if the cyclones had made up their minds to upstage Bhagwan’s munificence.

Parsad would tell the boy how he regretted all his life that he had prayed so hard for a boy that he had forgotten to pray for Parvatti’s health. Aunt Lalita lost three babies in succession, and Uncle Sukhdeo despaired of ever becoming a father. In the beginning he had looked upon Raju as his own, and had indeed assumed that if one day he ended up rich, the boy would inherit it all at his death. Still husband and wife prayed assiduously to Durga, begging her to give them even a girl, but sometimes the gods turn a deaf ear to one’s pleas. Many people said that this was why Lalita had turned sour, while others whispered between themselves that the wise Durga Devi knew what she was doing. She knew that Lalita, with her bad character, would make a terrible mother.

Lalita never looked upon the friendship between the two men with favour. She obviously resented the fact that her husband seemed to prefer the company of his friend to hers.

Phoopi had looked after the boy with love and care. She couldn’t do enough for her little prince. Oh he is so handsome, so sweet-tempered, she would say to herself as she gazed at him endlessly as he slept in the little wooden cot that his Baba Parsad had made for him from kankra wood with the help of his good Musselman friend the Hakeem who made his living as a carpenter. He had sawed and planed the wood Parsad had brought from the forest when he went honey picking.

Raju grew up without serious complications, learnt to walk and speak, sing and run and in no time at all he was well able to row and punt the little boat all by himself. As he had no siblings, he decided to adopt a little orphan boy two years younger than himself called Jayant, who, having lost both parents during a monsoon storm, lived with a boatman uncle and his wife. This boy was devoted to Raju, and called him Bhayya, big brother.

Phoopi was never at ease when Raju took the boat out, saying that it was leaky and falling apart. Baba, who seemed to have an answer for anything, taught the boy to swim. She then started worrying about sharks, and this time, all his Baba could do was to laugh, since he realised, after a quick calculation, that he would never be able to kill all the sharks. Baba always talked about teaching the boy some reading and writing but never got round to it. It was left to Phoopi to teach him, but fact was she did not know too much herself, although she had an amazing capacity for counting in her head. Often Sukhdeo, who would develop a talent for making money, but had no head for figures, would call on the family, tell Phoopi how much of such and such he had bought, what he had sold, who owed him what, and ask her to calculate his takings. Apparently she never put a foot wrong.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA b k

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA b k

When Raju was growing up, the family was squatting on some land which seemed to belong to nobody, and made a living by growing and selling their own vegetables, tomatoes, beans, bhindi, brinjal, palak, onions etc, bartering some with other villagers for things they did not grow in salty earth, like aloo and dudhi. They also had some hens which produced eggs for the family. Baba was a very skilful fisherman and the waters were teeming with the tastiest fish in the land, bhetki, parshe, pabdam bacha and many others, and he knew how to lure them into the traps he made from golpata fronds or at the end of his hook. They filleted easily, and when salted and dried could be sold in the Parganas or even Calcutta, although the wholesalers paid a derisory price. The Bagda Chingri found in the muddy waters near the shore were much sought after, and these too dried easily and brought a small income. That was Phoopi’s job, and she was happy to do it, feeling that she made a contribution. Baba was not too happy about this, saying that he had seen sharks lurking in the area, and people told of how some unfortunate women regularly lost a leg there. On top of everything, the best Bagda Chingri were those caught during the monsoon when the currents were dangerous, and a good few women had been carried away by the torrents. However, unless one took risks, one starved.

The most lucrative pursuit was honey gathering in tiger-infested country. Raju learnt at an early age that constant danger was as much a part of life as manure was to agriculture. Part of the fun of eating fish was sucking on the bone avoiding getting one stuck in your throat. Raju was so proud that his Baba and his Phoopi were completely fearless, and had no doubt that Ma was made from the same clay. Bihari folks know no fear, Baba often said. Bengalis said Bihari folk had big mouths.

Raju was always disappointed that when he went fishing with Baba, they saw not one single crocodile, not one shark. He sometimes dreamt of meeting a massive crocodile at the riverside and that he had beaten it away with nothing more than his oar, ramming it down the beast’s throat. He often bragged that his arms were so strong that if one day a crocodile had the misfortune of encountering him, he would grab its upper jaw with one hand and the lower jaw with the other and pulling with all his might, he would tear the brute’s head apart. He could not understand why the adults in the village were in such awe of the reptile.

When he loudly proclaimed all those imaginary feats, Baba would smile and nod approvingly, although Phoopi would sometimes bite her lips and shake her head. She feared that his intrepid nature would land him into trouble one day.

Baba was adamant when the boy announced that he was joining the honey gatherers. No, he said, not before you turn fifteen, it’s too dangerous. He argued that he had often heard Baba swear to the needlessly apprehensive Phoopi that honey gathering was completely safe if only one watched every single step one took. Baba continued to say no, and in the end when the boy would not give up, he promised him a slap on the face that will tingle for weeks if he did not shut up. That was usually the last thing Baba said when he was at a lost for words. He had never raised a hand to the boy and knew that crocodiles would grow wings and fly before he would. Still, that threat issued at some crucial point usually shut the boy up- for a whole hour. He must have been just over ten one day, when to Phoopi’s horror, Baba said, ‘Raju, beta, you have been pestering me for so long now, if you promise you will do exactly as I tell you, I will bring you along next time.’ Although Sukhdeo owed money to Baba, his influence had grown to the extent that the honey pickers, all Bihari men in their early thirties, as well as the buyers, considered him as the boss. Baba had a team of eight working under him.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Juggadery

Photo Credit:

CC-BY Juggadery

The boy thought that the risk of being attacked by a man-eating tiger was the pinnacle of excitement. He was not afraid of Dakshin Rai, he’d pick up a sharp stick and drive it through his throat, he would! He had killed many a crocodile in his dreams, and a tiger was not half as fearsome…

He had been unable to sleep when he woke up hours before dawn, fearing that Baba might forget his promise. It was the most unforgettable day of his life. Every step one took was a thrill. First there was the lengthy boat journey which would take them to the islands where the bees made the best honey. Although he was already a dab hand at being in charge of a boat, and thought no more of rowing or punting than going out for a walk in the bush, the knowledge that this time, it was only the beginning of an odyssey added extra chillies to the sauce. It was like a ride on that magic jaggarnath on the way to the stars in Baba’s stories, full of unexpected twists and turns. The most fun of all was the wearing of the face mask. Baba had made a small one for him, from half a coconut shell, had carved it, painted two fierce larger-than-life eyes. To fix it to the head, he had made two holes through which ran some rope made of coconut fibre which Phoopi had weaved, for home use and selling. You wore it at the back of the head to fool Dakshin Rai the tiger. Tigers never attack men from the front. They pounce on their quarry from the back, aiming fangs and claws for the spot just below your neck where the spine begins, causing instantaneous death. When they see a human face staring at them, they wait for them to turn round. This strategy allowed their prospective victims to escape. At an early age, when Raju heard the story of the mask, he wondered why mask or no mask, he never stopped hearing stories of tigers killing honey gatherers, but he kept this thought to himself. Anyway no one from Baba’s team had ever had a brush with Dakhsin.

When they reached the island, the first thing they did was to make for the shrine of Bon Bibi to placate the Goddess with a gift of bananas and coconut milk and to beg for her protection and blessing. Everybody knew that with Bob Bibi’s protection, Dakshin Rai all but became toothless. Forget Bon Bibi, and you were as good as dead, for the forests had more dangers than just man-eating tigers. Apart from king cobras and crocodiles, there were swamps which swallowed a fully grown man in seconds and countless other hazards.

The boy relished wading knee-deep in muddy clay which gave one a feeling of being twice as heavy as you pulled your feet up- the very opposite of swimming, which made you weightless. It was true that even as a child he had been fearless. He had the certainty that if he willed it, he could walk through a raging fire unscathed, that a massive tree falling on him would do him no damage; he would hold his breath and contract his muscles and the trunk would simply bounce off his body. He noticed that everybody was talking loudly and making a lot of noise, and understood that this was a tactic used to let Dakshin Rai know they were around so he would keep away. He watched every step, and was convinced that if Dakshin Rai had not shown up on that first day, it was because of his extraordinary vigilance.

Gloriously, he was the first one to spot a massive honeycomb hanging from a leafy keora. That boy has got the eyes of a tiger, everybody said loudly (the more noise the better! he was told.) For no reason everybody fell silent now, and wordlessly the team began to set alight the leaves and sticks they had been carrying with them, with a Lucifer match, to create smoke to stun the bees and make them fly away in confusion, buzzing angrily, but attacking no one. Once the preliminaries were out of the way, everybody came to the boy and tapped him on the shoulders, saying “Shabash! Shabash!” “Ya Bhagwan, the boy is a natural, spotting that honeycomb like that!” Now you watch for Dakshin Rai, with your fantastic eyesight, you won’t miss him if he approaches. He would have wished to be given the honour of making the first harvest, as he had spotted the honeycomb, but Baba made ready.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Nasa Johnson

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Nasa Johnson

How proud he was to see his old man put the curved knife in his mouth, his basket dangling on his left shoulder, walk towards the tree with a smile on his face, wrap his arms and legs around the bark and begin to hoist himself up with the speed of a young boy tearing down a sandy slope. He watched him in admiration. When he was level with the honeycomb, he stopped, held himself on a branch with one hand and firmly entwined his legs round it. With the knife in the other hand, he began to slice chunks off it, dropping them in the basket. That day they bagged a record harvest, and their spirits rose as they realised that they would be making good money. How everybody laughed and jumped about as they sampled their harvest, smearing each other merrily, chanting Bhojpuri songs and prancing about.

They left it for three days to give the honeycomb time to replenish itself before they returned. It was on this second trip that Raju saw his first tiger. He was stunned by its awesome beauty and by its size. It seemed to him that he was the length of a grown man. He was sleek and moved in utmost silence, his paws scarcely touching the ground. The boy was specially drawn to the way shoulder bones of the beast stuck out and went in as he moved. The men made the biggest racket they could, and Dakshin looked at them, yawned, turned round and walked away in disgust, as if bored by the shenanigans of humans.

Apart from honey gathering, Sukhdeo was involved in a large number of other commercial activities and Baba was his right-hand man. Time was when Parsad was the driving force behind the two-men partnership, but at the death of Parvatti, his erstwhile vitality had dried up like a nimbu squeezed out of all its juice and then left in the punishing sun. His mind had lost its sharpness, and he was quite content to play second fiddle to a man he had so clearly towered above in every respect in the old days. Many villagers grew various things on small plots of land on which they were squatting, and Sukhdeo had an arrangement with them whereby he handled their produce for them. At first, according to Phoopi, he was reasonably equitable, but once he discovered that he could, he began to demand a bigger cut. He and Baba were best friends, but he proudly repeated that business was one thing and friendship was another. If Baba was ever in need, he’d sell his soul to help, but under normal circumstances Parsad should not expect preferential treatment. He still conveniently forgot to repay the loans Parsad had made to him when they had left Allapur. When Phoopi mentioned this, Baba expressed his disapproval by drawing some air through the nose, sniff and turn his face round as he expelled it, shaking his head almost imperceptibly, saying nothing.

Sukhdeo sometimes provided small crafts for people who wanted to fish, and Raju did not understand why Baba who was so full of resources, never made a boat himself, or at least get his friend the Hakeem to help him make one for him. As a result, more than half his catch automatically went to Sukhdeo.

Fortunately Phoopi was quite expert at fishing for shrimps and prawns which needed no boat, as these grew near the muddy shores. She also made her own basketwork and used them deftly to land in good catches, which she dried in the sun and bartered with other villagers for other commodities which they produced.

Although Sukhdeo was noticeably much more prosperous than the other villagers, he had not as yet bought any land. He had not yet made enough money to be in the same league as Ishwarlal. The zamindar had arrived in Bengal a few years earlier, and had ended up owning valuable land. The jealous Sukhdeo loudly proclaimed that Ishwarlal was a crook. This conclusion was based on his oft-repeated conviction that no one ever became rich by honest means. One day, he promised, I am going to have more money than that crook.

It was that same year that Sukhdeo began to lay the foundation of his wealth, although Raju would only understand the ramifications much later. He was there, and later he would remember everything. The honey-picking season lasted no more than two months every year, as the moment the flowers began to wilt, the honey turned bitter, and was of no use to man or beast.

One day, as Parsad and Sukhdeo sat under the peepul tree, pulling on their bidis with furrowed brows, and enjoying a cup of toddy, the latter wondered aloud about the possibility of removing the bitterness from the late honey, perhaps by adding something to it, so it could still be sold. Baba suggested, half in jest, that they could give people some good honey to taste first and then sell them the bitter stuff. Sukhdeo laughed, but said that this could prove dangerous, as the buyers might make trouble next time round. Baba gave no more thought to bitter honey.

A few days later, Sukhdeo came to their little hut and said that he had found a foolproof method for making money with bitter honey.

‘Yes?’ said Baba. ‘Kaho, kaho!’

‘It’s like this: we will go to Calcutta and sell the bitter honey and tell people it is a miracle drug which will cure anything.’

‘Anything?’ Yes, pains and aches, winds, colds, you name it.’ Sukhdeo said. Baba thought the scheme might just work. After all people believed that the more bitter the medicine the more potent it was.

‘We could get your friend the Hakeem to come with us and testify to the quality of the product,’ said Sukhdeo, but Parsad shook his head.

‘That man will never tell a lie, not for all the water in the Zam Zam, as he says.’ Sukhdeo was not so sure, but suddenly Parsad’s face lit up.

‘Your mentioning the Hakeem gave me an idea, listen with both your ears.’

‘I am, yaar, I am.’

‘The Hakeem told me about something he read many years ago. Tell me, yaar, what does a man want value more than anything else in the world?’

‘Money?’

‘Money, yes. But money cannot buy everything.’

‘No?’ Sukhdeo paused for a very short while. ‘Course it can, what can it not buy? Tell me, yaar.’

‘If you were an old man and were no longer able to… eh… perform, would any amount of money make it stand up again?’

‘Methi Paak? Garlic?’ Methi Paak was a prized sweet containing fenugreek and nutmeg.

‘Doesn’t always work.’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ laughed Sukhdeo, ‘I don’t need it yet. Do you?’

‘Any man would give an arm and an eye to be able to do at fifty what he could do at twenty five.’

‘Bilkul!’ Absolutely.

‘And what I am saying is that bitter honey is that miracle product.’

‘Is that true? I never knew,’ Sukhdeo said foolishly.

‘Listen, yaar, people may not believe true and simple things, but when it comes to a promise of… how shall I put it…? Becoming younger…’ and Parsad made a fist and pumped it backwards and forwards a few times, in a familiar sexual gesture, ‘they will readily believe you.’

‘You think?’

‘The idea came from the Hakeem, it was he who told me that he had read about a type of honey from the Himalayas which indeed had the ability to raise the dead. We can tell people our bitter honey will help them get it up again… they will believe us.’

But it was Sukhdeo who carefully elaborated the nuts and bolts of the operation, thus justifying to himself that it was his idea, and keeping the ill-gotten gains for himself.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND seb.p

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND seb.p

They made for a part of the Hooghly river where hawkers from all over the area came to sell their wares. They used to sell a small earthenware pot of their best honey for two pise, but this time they asked for twice the price. One whole anna? People asked, how come? Sukhdeo winked and asked the hesitant customer if to him bed was just for resting his tired bones now. At the end of the day, their stock was depleted and Sukhdeo went back home with a small fortune. They were not sure how they would be received on their next visit, but prospective buyers were already queuing up, swearing to the potency of this Sundarbans Bitter. Sukhdeo surprised Baba by his quickness of mind, explaining that his suppliers were asking for more, and that one pot would now cost two annas. They were surprised when people readily disbursed. Many clients were all smiles and swore that the miracle drug was indeed potent, and with little encouragement recounted to all and sundry how they had kept their wives awake all night every night since they sampled the product. The Hakeem who did not condone such practices, explained that in such matters, often all one needed was faith and self-belief.

At first Sukhdeo had shared half the gains with Parsad, but Lalita frowned upon what she called her husband’s stupidity, and soon put an end to that. Arrey, why you give this lay-about so much? Why do you always put his interest first? What about me? Do I not work hard? Are you calling me lazy? Is that what you are saying? In the beginning, nothing she said made any difference, but gradually he started mentioning imaginary expenses, and ended up by keeping a bigger share of the loot for himself.

‘Friendship is worth more than money, Didi,’ was Baba’s explanation to his older sister.

However, almost imperceptibly the relationship between the two men became strained. They still met regularly under the peepul tree by the stream to smoke their bidis and indulge in their toddy, more by force of habit than anything else. They were not heard to laugh as much or as heartily as in their carefree Allapur days.

By now, Raju was considered grown-up enough to start doing man’s work. Everybody agreed that he had Parsad’s dexterity, and he took great pride in holding the curved knife between his teeth like Baba, as he climbed the honey tree to cut off chunks of honeycomb. He knew how to entwine his legs around the trunk before hoisting himself up. He had learnt all the rules and all the tricks. Above all else, he knew what only the best gatherers knew: when to stop. You did not cut the whole honeycomb off in one fell swoop, you needed to leave enough behind for the bees to rebuild on. Often the greedy or inexperienced gatherer took too much and spoiled it for themselves.

Many a time they had spotted Dakshin Rai, and managed to keep out of his way. In five years Raju had not witnessed a single mauling. The young man was never to lose his great love for honey-picking, not even after what happened to Baba.

Parsad was, as ever, terribly proud of his boy, and he would declare this openly to all and sundry. When he started making rash statements, his team mates became uneasy, although opinions were divided. When you say Dakshin Rai can come for me now and do his worst, some argued that it was inviting tragedy, whilst others maintained that on the contrary, when Dakshin heard this, he knew that the speaker had a fearless soul and should be left well alone. Anyway, Baba began saying, with a laugh of course, that as his boy could do this job as well as he, Parsad, Dakshin could come for him now. He should not have said that, for Bon Bibi must have misunderstood and thought Parsad no longer wanted her protection. The villagers would argue endlessly about the cause, but the fact was that Dakshin acted upon this.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Valerie

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND Valerie

One morning, Baba was unusually happy and relaxed, although he had been quite tired lately. His good humour was infectious, for everybody in the team was relaxed and was singing humming, and telling stories. It is said that a relaxed atmosphere was prone to attract danger, as people lowered their guards. Dakshin Rai appeared suddenly from a bush and almost before his presence was registered, ignoring the face mask at the back of Baba’s head, he pounced on the unfortunate man from behind and made for the top of his spine, which is what he usually does. Death was almost instantaneous. Baba fell down, his eyes wide open. He just whispered, “Bodh Gaya!” and expired with a smile on his lips. The others fearlessly drove the killer away with massive sticks, but it was too late. Sukhdeo cried like a child and everybody else began beating their chests, crying their eyes out, except Raju. He kept shaking his head. No, he kept saying to everybody, my Baba is tired, he’s just gone to sleep but he will wake up soon and none the worse for the attack. Why was everybody crying? For three whole days, even after Parsad was cremated, Raju was convinced that something mysterious had occurred, and that Baba would turn up soon.

Raju avoided people. Whenever anybody said anything to him, he stared at them with vacant eyes and seemed not to hear. The only person whose presence he tolerated was the Hakeem. He would walk to his little hut by the water and sit on the ground quietly, saying nothing, watching the man Baba admired above everybody else sawing or planing wood. The Hakeem was not given to making long speeches, and would leave the boy to his thoughts. Only when he was going back to Aunty Umma after maybe two hours, would the older man take him by the shoulder and hug him. One day he grabbed his hand as he was walking away.

‘You know beta, I have not seen you cry for your Baba, why?’ The young man did not answer.

‘It is not shameful to cry for your dead father, even the bravest warriors shed tears for their dead comrades.’

‘I know,’ he had said weakly. On the way home, a thought struck him. If I cry now, I will feel less sad tomorrow, but I want to feel sad for the rest of my life. I will keep my tears in, I will never cry for my Pitaji so I can be always sad. This made him remember how loving Baba was. All his life he would remember the stories he had told him. He specially cherished the memory of how he would press him to his heart before he fell asleep. He would force the tastiest piece of Bhetki in his mouth, saying, eat, beta, eat, when you eat Baba’s hunger is gone. He remembered how he had carried him on his shoulders from Jharkhand to Calcutta, singing his funny ditties. Prey to all those remembrances, he had to sit down under a bush. The clouds which had gathered in his skull suddenly burst and rained tears which burst through the banks of his eyes. He did not know for how long he had cried, but when he woke up, the sun had set. This gave him a lot of comfort, and did not make him feel bad. It felt like a homage to the dead man. Later he would try to relive the events, but it was never the same.

Sukhdeo said to everybody that as long as he lived, his friend’s son and sister would want for nothing, but only once did he give Phoopi Umma some money. He loved saying things like this when there were people around, and he would loudly proclaim that whenever she wanted any help, be it midday or midnight, all she had to do was to ask, in the hope of seeing admiration in the eyes of the bystanders. Midday or midnight, yesterday or tomorrow, admiration was what he craved for. After that first time, he never gave or offered her anything, and she never asked. The proud Phoopi had told herself that she would starve before taking any money from a man she had always despised.

Raju was not really able to earn a reasonable living by himself, as Sukhdeo gave him less than the other honey pickers, saying that grown-up men and youths could not be paid the same rate, although the boy did the work of two.

On top of her fishing activities, Umma made a few more annas by offering her services as cook to the richer folks when there was a festival, or by darning other people’s clothes, knitting woollen bonnets for babies. Still, most of the villagers were even less fortunate than themselves. In any case, it was rare for anybody to go hungry in the Sundarbans if one was prepared to eat the same fare day in and day out, there was any number of comestible greens as well as nuts and roots growing abundantly around.

Unsurprisingly, the Hakeem who himself barely scratched a living from the little carpentry that came his way, making a boat now and then, supplementing his meagre takings by his healing work, which he did mainly for free, was always there for them. People thanked him by bringing him eggs or beans, milk or curd and similar things, and these he happily shared with the orphan and his aunt. More than that, he became a second father to Raju, giving him guidance, but most of all he taught him about the magic plants of the Sundarbans. In the beginning, he would go to the forest with the teenager to reveal to him the secrets of the flora, and tell him stories associated with them. The old man was a fount of wisdom, and taught him which plants were good and which to avoid.

‘Never walk under this tree,’ he told, as they were approaching a nona jhaw, ‘it brings bad luck. You see, it bears no fruit, and if a woman walks in its shade, she becomes barren.’

‘But I am not a woman,’ Raju protested in jest.

‘Well,’ the Hakeem winked, ‘do it, and you’ll never become a father.’ The most unforgettable experience the lad had was with the bhola flower, a type of hibiscus which prospered in the marshy salty soil. It immediately filled you with delight when one suddenly leapt at you in the forest. It is the prettiest flower one is likely to come across, golden yellow petals with a red centre.

‘Look at this one here,’ ordered the Hakeem, ‘stare at it and concentrate.’ For five minutes nothing happened, then suddenly, Raju could not believe his eyes when the yellow petals started darkening, first becoming golden yellow then orange. Raju was not one to keep his surprise silent, and began to exclaim his appreciation, but the Hakeem ordered him to be quiet and to keep looking. The deep orange now turned red, and in a matter of minutes, the whole flower detached itself from its stem and fell to the ground. He had never witnessed such a miracle in his life.

Thus it was that Raju became an expert in the field, and in gratitude he would bring his mentor whose knees made walking more difficult everyday, a regular stock of his medicinal leaves, roots, bark and seeds: Lata hargoza seeds which he needed for people to cleanse their blood, Passur for stomach pains, math goran for ulcers, harguja with was the most effective remedy against rheumatism as well as a large variety of other plants like amur, kripa, or dabur.

Sukhdeo did not view this friendship with a good eye, and one afternoon he arrived in Roshankhali on Jayant’s boat and made for the little hovel where aunt and nephew lived.

‘This Musselman is trying to convert the boy to Islam and make him eat beef,’ he told Phoopi, but fortunately the wise old woman told him that the Hakeem often told the boy stories from the Ramayana, although he himself was not a Hindu, so how could he be trying to convert the boy? Sukhdeo was not going to give up too easily.

‘The man is a charlatan I tell you,’ he exclaimed in desperation.

‘I know you went to see him about your flatulence and you’re still spoiling the air whenever you go anyplace,’ thought Umma.

‘How can you be saying that? So many people he has been curing,’ she said instead.

‘Nonsense, if he was such a great Hakeem, how come he cannot be curing himself of his bad knee?’ Phoopi was stumped, but only for a short while. ‘Sukhdeo Bhai, no one can be cured of old age.’ The malicious man was still not beaten.

‘He is only using the boy to bring him all those quack herbs he uses to fleece people,’ Sukhdeo said. ‘He is wearing rags and telling everybody he is poor, but I have heard that he has rupees and gold sovereigns hidden in the ground.’ Umma and Raju both knew that “Somebody” was another word for Lalita, and Raju’s aunt pointed out that everybody extols the virtues of the man who never charged anything for his healing work.

‘But people are always giving him things,’ Lalita’s husband said, ‘dried Bhetki, eggs, chicken even… I am not knowing, so many things…’ Umma thought that it was best to keep quiet.

‘Your Baba who was more than a brother to me,’ he told the boy, ‘was a friend of the Hakeem, but he would not wish his son to associate with a Musselman like this, specially as I am a second father to you.’

Raju was very astute. ‘Chacha Sukhdeo, remember the Hakeem cured you of those pains in your knee, he’s a good man to have as an ally.’

‘Cure me, you say? hraak! All he does when anybody has an ailment is to get you to eat cabbage, put cabbage on your aching knee, chew cabbage when you have toothache, drink cabbage water when you have stomach pains… all that cabbage does is to make me fart, your aunty Lalita says…’

‘It’s not the cabbage, Chacha, everything makes you fart,’ the boy was going to say but bit his tongue in time to stop the hurtful words.

‘Chacha Sukhdeo,’ he said instead, ‘I am thrice blessed, for I have three fathers: my poor Pitaji who always watches over me, your good self, my second father, and a Musselman for a third father!’ The older man was very angry, but thought that he would bide his time.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND photosinframes

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC-ND photosinframes

Now, when Raju went honey picking, he came back loaded with the good things of the mangrove, the excellent golpata shoots, hental dates, not only gila roots and nuts, but also its bark which is used as soap, khalsi or dulya bayen twigs which proved to be excellent firewood, edible fruits, passur twigs which he gave to friends who had stomach problems, keora leaves for the goats and cows, and their edible fruits which Phoopi boiled or roasted, or cooked with sojne. The Hakeem had taught him how to collect the tasty ashilata beans which made one strong (‘you’ll understand when you are older, beta’). But make sure that you did not let the hairs touch your body, as they had an itchy effect on one, he warned.

He knew how much Sukhdeo resented the Hakeem, and understood that he viewed it as an affront to himself, as if he could not be friends with both of them. Gradually the older man’s attitude towards him hardened. It was as if he wanted to end his personal relationship with his best friend’s son, but Raju knew that the man needed his sweat.The astute businessman swallowed his resentment and began involving him in his multifarious commercial activities, the sort of thing Baba had been doing for years. Clearly Lalita had made sure that he did not pay him a full wage.

It was this which prompted Raju to think of new schemes. He would build a boat with the Hakeem’s help, and use it to go fishing on his own account. Sukhdeo reacted angrily to this, told the boy that as his guardian, he should have been consulted before embarking upon something so reckless. Did he not know the dangers? Did he wish his Phoopi Umma to be left destitute if something happened to him? He reproached the young man for treating him with such little respect. He had never once done the p’rnaam to him, never prostrated himself in an attempt to kiss the older man’s feet like one is expected to do to an elder to whom one owed respect and allegiance. If Raju had thought that was what was expected of him, he would have done it for form’s sake, but the idea had never occurred to him. It was true that he never asked for advice, even the doting Phoopi had to accept that her nephew thought he knew it all.

Gradually, by his commonsensical approach to work, the boy had ended by earning the older man’s grudging admiration. He sometimes forgot himself and declared that if Bhagwan had given him a son, Raju would have made a good model, but he quickly changed the subject. Deep down he could never forgive him.

It was Sukhdeo who suggested to the young man one day that it was time to marry, and went as far as to suggest that he would find him a suitable bride. Raju liked the idea and giggling happily, agreed. When the older man mentioned the daughter of a honey-picker called Kamla, Raju remembered her as a very plain sort of girl who he had never found in the least attractive, and said so. Who do you want as a bride then? Sukhdeo had asked angrily, Ishwarlal’s daughter Shanti? Raju’s eyes opened wide. He had always dreamt of Shanti, but expected that the daughter of the rich zamindar would end up marrying the son of a rich man from Calcutta. No, Uncle Sukhdeo, I am too young to marry at the moment, but the seed of an impossible romance had fallen on fertile soil.

It was Phoopi who now began to have a go as well. She said that Raju could tell her if there was anybody he liked. Cheekily he only mentioned Shanti’s name, in the hope that she’d leave him alone. He reasoned that Ishwarlal who had always treated him with disdain would never agree to such a union, but Phoopi said, why not? With little to lighten her gloomy existence, she often found solace in the fact that back in Bihar their ancestors had once been rich landowners and were of a much higher standing than Ishwarlal’s. She told her nephew, ‘Your grandfather was a poet, we had hundreds of bigha of land. Ishwarlal comes from a family of dhobis, earning their living by washing other people’s dirty linen,’ adding that nobody forgets things like that. She was convinced that Raju would have been an excellent match for anybody. He was a respectable and handsome young man with excellent prospects. If anything, her nephew was too good for that family.

One morning, she scrubbed herself, washed her hair with soap and put on a white widow’s sari, found an old pair of dried up chhampals that she had not worn since she arrived in Roshankhali, cleaned it, mended it, found it bit her now bigger feet, but decided that for her nephew she had to look good. With determined steps, she came out of the house and made for Ishwarlal’s. She had once been friends with Radha in Allapur, but this was the first time that she was going to visit her here.

She suddenly remembered her stoop and stopped suddenly. She took a deep breath, straightened her back at great cost to herself, and pursued her route. Radha received her with great warmth and courtesy. Although she expected no less, she was flattered. She went straight to the point. Good husbands for our daughters are very hard to find, she began, and Shanti’s mother agreed. Feeling encouraged, she launched into an elegy of her nephew, which, because it was so heartfelt, struck the other woman as very convincing. Yes, Umma didi, conceded Radha, so I have heard. She had? He is going to go far in life, assured Phoopi. Radha said she would mention her visit to their father.

Ishwarlal, a sound businessman used to weighing the pros and cons of all deals, agreed that Raju was poor but had great potential. He remembered that the boy reacted with maturity when he gave him a hard time as a child, he neither cried, nor looked at him insolently.

‘Yes, the boy has great potential. When I buy a piece of land,’ he told the bemused Radha, ‘I do not look at the rocks and stumps and dismiss it as barren. I wouldn’t be who I am today if I did. On the contrary, I visualise it after the impediments have been removed and after I have tilled the soil, watered it, ploughed in the best cow shit. Yes, piari, you can call me a man of vision if you insist. The boy will indeed make a good husband for our beloved daughter.’ He decided on the spot that the young man should come work for him, for each other’s mutual benefit.

Sukhdeo was flabbergasted when he heard about the proposed union. His feelings for his dead friend’s son were so confused. Sometimes he loved him like the son he never had, and at others, he felt an inexplicable anger mount in his breast and had to stop himself doing him physical harm. He admired his devotion to work, but at the same time was jealous of this capacity. However, this prospective marriage gave him no joy. He wanted the boy to do well, but not that well. Lalita saw it as a union between two different and unequal species like between a dog and a lioness. No good can come out of this, mark my word, she said. This thought gave her husband a jolt. No piari, he admonished, don’t be like that. Don’t be the goat’s mouth that turns everything bitter on the vegetable patch by just one bite. Parsad’s boy needs our blessings.

There were problems from the very beginning. When Ishwarlal told Raju to come work for him, Phoopi told the boy that it was never a good idea to work for your in-law, pointing out to him that he had excellent prospects and did not need patronage. ‘You do not want to be beholden to them.’ she advised. ‘You work for your father-in-law, and you become clay in the hands of your wife. She will never let you forget that you owe her family everything, they turn you into a burbak.’

The zamindar was in a fix. First Radha had become sold on the idea. Worse, they had told everybody about the impending wedding. A break at this stage would make Shanti unmarriageable, as tongues had already begun wagging. Ishwarlal decided to shrug this incomprehensible stance, telling himself that the boy was bound to come round soon enough.

Then it became apparent to aunt and nephew that plans were being made for them to move in Ishwarlal’s house until he had another house built for them. This time it was Raju who did not relish the idea. He wanted to be the boss in his own house. On learning this, Ishwarlal thought that enough was enough. In a fit of anger he shouted at Radha, accused her of going ahead with a hare-brained plan without talking to him, and proclaimed that the wedding was off. But Radha had taken a shine to the young man, and although she did not defend herself against Ishwarlal’s unjust remarks, she knew that in the end, she would have her way. All that happened was that the wedding was postponed for three whole months until Raju had finished the repairs on his dilapidated dwelling, under the supervision of the Hakeem and with Jayant’s help.

Ishwarlal was not a happy man when the big day came, but he had no choice. Shanti, on her part said nothing, but after what she had heard of Raju and seen of him, she was hopeful that he would make no worse a husband than those of her married friends.

Shortly after the wedding, Phoopi Umma died suddenly. She woke up fit and cheerful, took ill at noon and in keeping with her nature, died without fuss within an hour. It was as if she had decided that Raju was now in good hands and she could let go. It was her dearest wish to see her grandchildren before she died, but Shanti only discovered that she was pregnant a week after she died.

Ya Bhagwan, cried Raju as he watched the flames rise from the ignited body of the dead woman, how could you be so mean to such a saint? Parvatti had never been more than a picture to him, but Phoopi was flesh and blood. All mothers loved their children, he thought, they had no choice, but Umma’s love for him had not been forced upon her. It was love in its purest form. She had never once raised her voice to him, never said one unkind word. Her every single action was dictated by her need to protect her boy and make his life happy. He allowed his tears to flow freely this time, but knew that he would carry the memory of the woman who had been both father and mother to him in his heart until he breathed his last.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Margie Savage (Beedie)

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC Margie Savage (Beedie)