Chapter 8: Pictou

(Canada, 1773)

Hughie dear boy, the letter began, I am writing to you from Pictou in Canada, where I have been these last few years. I am writing to tell you that I never meant to abandon you and your Mam, but when God made me, he used two different types of clay, so part of me is weak-willed, whilst the other part is a man of surprising strength and courage. Sometimes the weak clay is stronger than the strong clay… I mean the weak man wins, like when I got drunk and thrown in jail and was too ashamed to confront your Mam. Honest to God, laddie, I worshipped the ground she trod, but anything above that ground, I was dead scared of. You see I had made a promise to her that I would never touch the devil drink for as long as I lived, and couldnae keep it. One advice I will give you, Hughie, never make such a promise, it is the devil itself to keep! I have touched no alcohol today, and mean to write a sensible letter to you, to say sorry to you and to explain how I came to land in this blessed place, for it is indeed blessed. I have to stop to pour myself a drink to toast that land, but no more than one, I swear.

Ha! Yes. As your Mam must have told you, time was when I was hoping to become a preacher; I was always very good with words, they told me, I was good at book learning and had a memory like a sponge that absorbed everything I saw and read. They said I drank like a sponge too, and I am afraid it’s true. Yes, I never became a man of the cloth, as I lacked discipline, they said. I liked my drink, I preferred playing the pipe to reading the good book, and I loved telling bawdy stories. Mam will explain to you what that means. But I never harmed no man. Sorry, I mean to write proper grammatical language, I meant I never harmed anybody! Anyroad, I became a crofter, but as you must know, I was no good at it. When I started playing my pipe, I forgot everything, and let the cows stray. Were it not for your Mam, the oats and turnips would have withered and we would have starved. I knew what was wrong, and prayed to the Good Lord to help me stay on the path of righteousness, but the weak clay was stronger than the strong clay. Och I said that already… As your Mam would say, God’s ears are deaf to the supplications of the poor. Your sister Morag died in her infancy, and it was my fault. I was heart-broken – Hugh had almost forgotten Morag!

When you was born, Hughie, I thought that it was the end of my woes, I prayed that I would have the strength to do right by you. I knew I could be strong. As you know at the Battle of Culloden, I came to within inches of slaying the Duke of Cumberland- which would have altered the course of history. Sorry, I need a drink to drown my sorrows here, I saw so many good people lay down their lives for Auld Scotland in this battle. I promise you, no more now. I am not going to describe to you how I chased the wicked Duke with my axe, managed to unhorse him… I will tell you all that in my next letter. Hugh smiled as he recalled what Mam had said.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC bri porteous

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-NC bri porteous

I want to stick to my story. I got drunk in Boath once, and lost my way. I found myself in jail for rowdy behaviour. I was too ashamed to go back home and face your Mam, so I roamed the land, playing on my pipe, drinking and making merry. That was when I found myself in Loch Broom. It was mid-July when I met some good people who told me that they were meaning to go to Canada where there was land aplenty to be given free to us Highlanders who were willing to seek their fortune beyond the seas. Kenny, I said to myself, this is what you have been waiting for all your life. You were a bad crofter because you had to give half of everything you produced to the laird; if you had your own land, you would surely take greater care of it. Aye, I thought, I would take the plunge, go to Canada, claim that land, build the best farm anybody had ever seen and send for you and Mam.

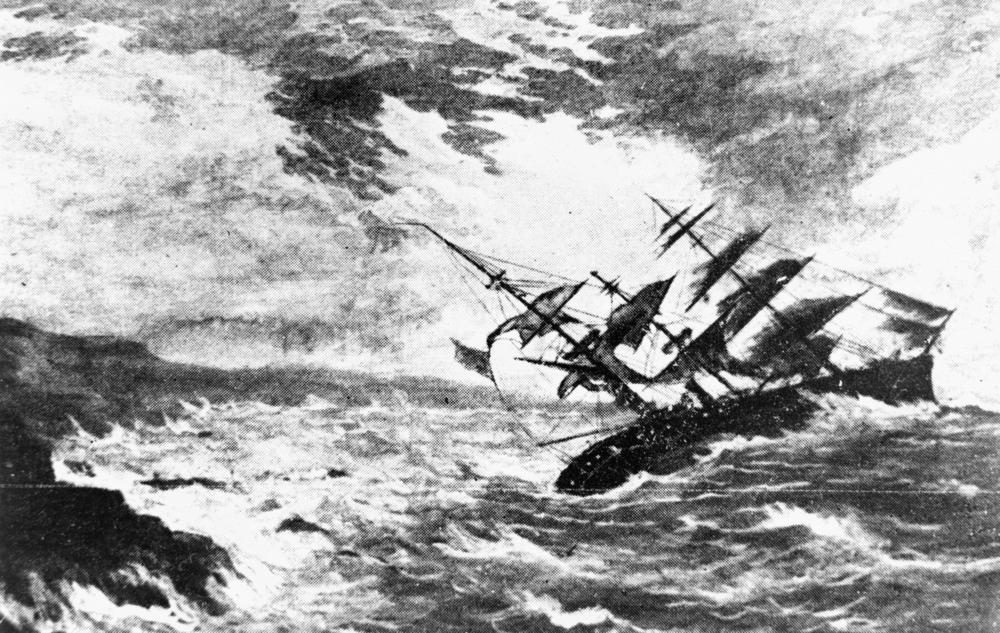

Honest to God, that was my sworn purpose. The ship was the “Hector.” I watched it coming in from Greenock, and my heart was aflutter. It was mighty big, I thought, almost one hundred feet long, three- masted, two hundred ton, Dutch made, and they know how to build ships them Hollanders, but folks said it was old and damaged, and many said that there was no guarantee that it would survive the raging storms on this eight week journey. But nothing was going to stop me, my mind was made up, I was going to take my chances. But there was one impediment to my aspiration, Hughie, I had not one brass farthing to my name, and Captain Speirs demanded three whole pounds sterling to take me on board. I begged him to let me come on board, swore that I would work for my passage, clean the deck, play music to entertain passengers and crew in times of hardship and danger, do anything, but he had a rock for a heart. The passengers coming in to join the ship took to me, as I would play my tunes on my pipe to entertain them while they waited. First the ship had to be rigged and when that was done, they had to wait for propitious winds. They took to me, the passengers, and would have raised the money for my passage, but with the uncertainty ahead, they were loth to part with the little they had themselves. On the day of the departure after the passengers had pleaded with all their might, the Captain’s heart melted. A true Scot heart is generous in spite of a hard exterior, Hughie, remember that.

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Dennis Jarvis

Photo Credit:

CC-BY-SA Dennis Jarvis

The ship had appeared quite big to me as I saw it enter the Loch, but the moment I set foot on board, I could not believe that two hundred souls were going to be accommodated in an area half the size of our stable in Strathruthsdale, but arrangements had been made for people to sleep in bunk beds four storeys high. It was pandemonium, dear laddie, how were the people going to manage? I wondered. How were they going to scramble on their allocated bunks without murdering each other? I decided to act. I did my utmost in calming down frayed nerves, repeating, No need to panic, dear friend, there is room for everybody if we organise ourselves. I succeeded in stopping any fighting that would surely have resulted without my intervention.

Shall I tell you about the voyage? Yes. The first few days went well; at first, everybody including the captain was sea-sick, except me, so from the beginning I played an important part in the running of the ship. I was the one who took the helm and avoided a head-on collision with an iceberg off Greenland when the captain was being sick. Thankfully we had a good wind but no storm. Mind you, we were two hundred souls altogether on that small brig, and it took a while before we got used to the stench, the crying of children, the moaning of the sick, the constant battering and buffeting we had to endure. We were fed more or less properly, nothing fancy, salt beef, oatcakes, turnips; the Captain had assured us that we need not go hungry, as there was adequate food for the two months the trip was going to take; the crew treated us well, and Captain Speirs was civil and sensible. I played my pipe every afternoon, to the obvious delight of passengers and crew, who could not have enough of my tunes, many of which I made up myself. I might have made a fortune as a composer! After I had avoided that rock that I mentioned earlier, the captain’s respect for me never stopped growing; he never took an important decision without consulting with me.

The first death from cholera took place a week after we had left Loch Broom, and eight people died in the next few days and were buried at sea; miraculously the epidemic did not spread, as the captain had feared. Naturally we mourned the untimely death of our comrades, but I urged everybody not to let gloom and despondency take over, and I am happy to say that they heeded my advice.

For six weeks or so, although it was not plain sailing we made good progress and the Captain confided to me: ‘Mr Mackenzie, eh, can I call you Kenneth?’ he said. ‘Keep this to yourself, I don’t want to give false hope to the folks, but I strongly believe that we would get to our destination a few days early.’ But I thought that it would be kinder to tell everybody, as this intelligence would make it easier for them to overlook the many hardships we had thus far encountered. ‘You’re a man of great wisdom, Mr Mackenzie,’ Captain Speirs said to me. I wish I had not prevailed, for all this was about to change.

Now words fail me as I attempt to describe what happened when we were within sight of the coast of Newfoundland. A storm the like of which none of the hardened sea dogs on board swore they had ever witnessed, started brewing. One child was thrown overboard, and the captain had to restrain me from throwing myself in the boiling seas to attempt a rescue. Some four people died of fractured skull as they were flung against the hull by the violence of the storm. Some more were to die in the same manner in the next few days. Although it was midsummer, a roaring cold cutting wind blew pitilessly, and the leaky Hector was in danger of keeling over and sink with complete loss of life . All the sailors were exhausted and had no strength left in their arms to work the pump. Thus the brig kept taking in more water than they were capable of pumping away, but for my timely intervention. Captain Speirs, I shouted, let me help. The sailors looked at me and made a passage for me. I do not know where I got the strength from laddie, but there was I, working like a demented soul at this Herculean task, and everybody looked at me in amazement. Surely they must have been asking where does such a frail man get all this energy. All the time, the storm was raging with hellish fury, the passengers were screaming and praying, Lord Help Us, Save Our Children, Why Did We Leave Our Dear Highlands? The ship was soon completely out of control and just drifted where the winds blew it.

It was at this very moment that the good lord chose for Anna McClean who had been big with child when she boarded the brig in Loch Broom, to go into labour. Everybody panicked; Captain Speirs who usually doubled up as ship surgeon was not in any condition to attend to her, he was a bundle of nerves; he already had too much on his plate, what with having to keep the ship afloat. There was no one around who could or would help coax out the little bairn that was dying to come see what a storm looked like. It seemed that I was the only one with any sort of qualification. I had after all had some farming experience and had delivered calves. I will do it, I said. Everybody gasped. Is there any limit to what the man can do, they must have been asking themselves. Someone brought me a basin of sea water to wash my hands with, and I immediately set to work. I made people move away, and Anna looked at me with gratitude. She seized my hand and pressed it, and I smiled at her and talked to her gently to reassure her. Trust him, he is a good man her husband Rabbie said to her needlessly. The good Lord guided my hands and I was able to deliver her of the prettiest little girl you ever saw. Everybody cheered aloud when she began to cry. She probably did not like the look of that storm! Someone gave me a pitcher of ale to which I did immediate justice. Friends, I said, this new arrival is a good omen; she has come to tell us that the new life waiting for us in Canada is going to be a good life, and everybody cheered.

When after three days the storm finally abated, the Captain called me and confided in me. Kenny, he said, keep this to yourself, I do not wish to cause panic, but we are lost. I have no idea where we are, my instruments are broken. It was a clear starry night and we were smoking our pipes and watching the sky. Suddenly I had an idea: Captain Speirs, I said, isn’t that the northern star up there? I said pointing to that star. Aye, he grunted. And that constellation there? I asked. The Plough, he said. Need I say more? I said happily. You’re a good man, Mackenzie, I am glad I’ve got you on board. You understand, dear boy, that gave him the idea to work out where we were, and what course to take after the sails had been mended and the masts repaired. The ship had lost two weeks, for that was what it took us to get back to the point where the storm had started playing havoc with us.

Now the real trouble started, for provisions were getting low on account of the lengthening of the voyage, and I advised Speirs that there was only one thing left: rationing. But they’re all going to protest, he said. Not if you tell them that it was either that or starvation when the rations were completely exhausted. He recognised the wisdom of my words and acted accordingly. As I had expected, everybody agreed that there was no other course of action possible, and ate stale bread that was turning green.

On the 15th of September 1773, the good ship landed at Brown’s Point in Pictou, with the 189 souls who had survived the trip. It was a sad sight that greeted us, Hughie; the landscape was flat and dreary in the extreme and looked quite unwelcoming. Now, we had been promised food for the next few weeks, until our seeds were able to produce, but the Captain admitted that there was practically no food left, a high proportion of the seeds having rotten away in the storm. He was going to set sail for Philadelphia as soon as possible, he said, in order to get us food and seeds.

When we landed, there was chaos and panic as the Captain was in a great hurry to leave us. The plots we had been promised were swampy and overgrown with thorns and thickets, and we had no equipment to make a propitious start. Discontent was rife and the prevailing anarchy might have deteriorated into riot and murder were it not for my taking charge.

We knew about English immigrants who had arrived some ten years before us and had settled in the region of Truro, but they were a hundred miles from where we had landed. Nearer there were Pictou Indians, and my idea was that we could ask them for help. The others proposed attacking them and taking what we wanted by force. I was against that course of action on two grounds; we had come to their country and had no right to ride roughshod over them, and on the more practical level, we were not properly armed for conflict, having but two guns between us.

Many people were for walking to places like Truro where our English cousins might give us employment, food and shelter. I was the only one in the group who could speak English properly, but I was not willing to beg. Make up your own minds, I told them, you follow your own ideas. Some of our numbers kept arguing that the natives had only axes and at least we had two guns, but I opposed violence with great vehemence. The settlers’ anger turned on me.

‘What are you going to do then?’ someone asked, ‘go to them natives on bended knees and beg?’

‘Its worth a try,’ I said without great conviction. They were very sceptical; many then decided to leave and go look for work and food. Fortunately the cold weather had not yet reared its ugly head. About half of our numbers took to the road. I do not know what happened to them; did the English treat them with sympathy? How many starved before they got anywhere safe? Did bears or other wild beasts make a meal of those poor creatures looking for a meal? I have no idea, Hughie, dear boy.

With a small party of volunteers from those who stayed behind, we made our way gingerly to where the natives were encamped, raising our hands in a gesture of peace as we saw them, but they immediately surrounded us, banging on their drums, brandishing spears and sticks with plumes on them, shouting and talking incoherently and jumping up in the air like demented creatures The party began to curse me for my stupidity, and I daresay many would have gladly stuck a knife in my back. Some began praying to the Good Lord to spare us.

‘They are preparing to kill us,’ someone said, and everybody agreed. ‘Maybe it’s their way of welcoming us,’ spat one vociferous fellow venomously. ‘Aye,’ said I, more in hope than with conviction, ‘maybe that’s what they’re doing.’ Suddenly amid the throng we saw a party of young women nearing us with meats and fish, and made it obvious to us by signs and incoherent words that we were to partake.

Photo Credit:

Encounter between John Guy and the Beothuk people in 1612, engraving by Theodore de Bry or Matthaus Merian, circa 1627-28

Photo Credit:

Encounter between John Guy and the Beothuk people in 1612, engraving by Theodore de Bry or Matthaus Merian, circa 1627-28

Needless to say, we sat down and devoured their offering. When we were sated, the Chief approached me and explained, by dint of sign language and some hardly recognisable English words, that they had but very little themselves, that the buffaloes had practically disappeared from the area, that the salmon and the muskellenge seemed to have deserted their waters too, and that there was very little lake rice to be found. They introduced us to the dulse, a reddish seaweed which could be picked up on rocks and which grows in the area between low tide and high tide. It is very nourishing but we found it difficult to eat this at first, it has a strange taste, however we soon not only got used to it but became very fond of it.

The Pictou natives told us that they had watched the “Hector” come in, with dismay and foreboding wondering what we were going to do in the land of their forefathers, but they were not hostile and gave us some food to take back to our companions, explaining that they did not have much to give.

We went back to the beach and our friends were surprised at what we had to tell them. The Pictou Indians had given us some good advice on where to find food, dulse and wild turnips, and it was thus that we managed to survive. We were not idle and set to work on our plots, working with our bare hands to clear the land, and when the first shoots appeared, our joy was great. Now, I have an admission to make. It had never been my intention to desert your Mam and yourself, but from the very first I noticed that Wahamaha, Chief Red Stag’s youngest daughter could not keep her eyes off me. Why, I will never understand, for I was never a handsome man; maybe she recognised my inner qualities. I will not beat about the bush, Hughie, we ended up getting joined in matrimony. You now have a young brother whom we named Robert Pictou Mackenzie, and a sister, Morag Wahamaha Mackenzie. I am now a very happy man- for the first time in my life. I am not going to say that I do not touch the devil drink anymore, but I now drink only moderately. I have never stopped loving you, Hughie, and it is my dearest hope that one day you will join us here, if your Mam will let you. I now have over one hundred acres of forest and land under cultivation, and will send you some money soon, and will write regularly.

I don’t suppose he ever got round doing that, Hugh mused, Mam never said.